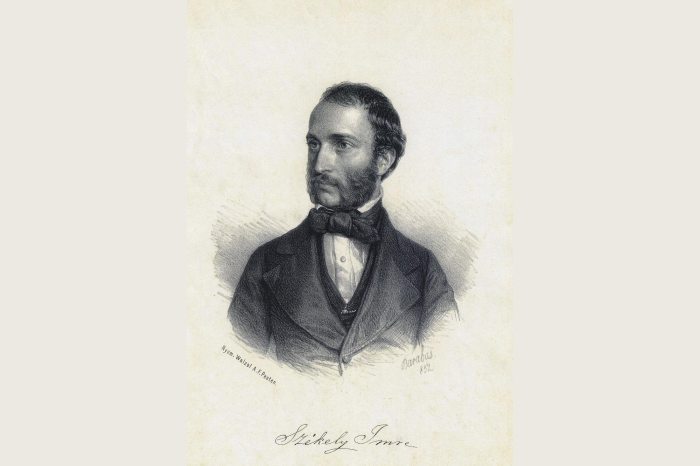

Modest virtuoso and influential educator in the shadow of Franz Liszt – Composer Imre Székely was born 200 years ago

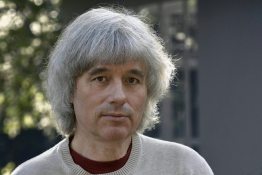

What do Alexandre Dumas's salon in Paris, Queen Victoria of Britain, the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, Budapest's oldest music school, the popular children's song 'Boci, boci tarka' and the Hungarian national consciousness of Romanticism have in common? Imre Székely is the answer: he was one of the most celebrated composers of his time, of European fame, and this year we celebrate the 200th anniversary of his birth. On the occasion of the bicentenary, we recall his figure with János Kéry, pianist and lecturer at the Academy of Music.

It is not a typical story, even in reform-era Hungary, that a talented young pianist born into a noble family can start his career with absolute parental support: no paternal reprimands, no sibling conflicts, and no poverty in the early years of his career. And Imre Székely, born on 8 May 1823 in a noble family in the Upper Tisza region, had this. Yet today we know almost nothing about him.

What could be the reason for this oblivion?

János Kéry believes that several factors have contributed to the fact that Imre Székely is hardly mentioned in contemporary Hungarian music history.

"He was a good composer, but not as outstanding a talent as Franz Liszt, but I would daresay he was on a high artistic level with Mihály Mosonyi or Ferenc Erkel - we know them, but not Székely."

The other reason could be the Hungarian style represented by Imre Székely. As he says: "If you say Hungarian music to someone anywhere in the world, the style of classical music that comes to mind is certainly the style represented by the above-mentioned". As an example of how true this is, János Kéry cites an episode from 1947, Tom and Jerry, in which the pianist Tom plays a Liszt rhapsody, namely the Hungarian Rhapsody II, while Jerry, who sleeps on the hammers and then wakes up, annoys him in various ways.

However, this widely popular Hungarian music, with its traditional melodies, fell out of fashion at the beginning of the 20th century, during the time of Bartók and Kodály. The Bartók 'from pure sources only' principle no longer allowed classical music fantasies based on folk music motifs - in Imre Székely's oeuvre, 'daydreams' - to be identified exclusively with the Hungarian musical style. Even if this did not change the assessment of Liszt's oeuvre, the minor composers, the second line, simply fell out of fashion.

The next reason, which may lie behind the oblivion, leads us to the history of the family and the origin of Imre Székely. He came from Mátyfalva, from a Catholic noble family, where, in addition to classical education, service to the fatherland was part of his upbringing, and this background may have provided the political basis for his neglect during the Monarchy and then during the decades of communism.

From the river Tisza to the limelight

Imre Székely's father was a law graduate in the county service, who kept nearly a thousand volumes of Latin, English, German, French, and Hungarian books and journals, played the piano himself, and taught all three of his sons to play music. Lajos played the violin, Imre the piano, and István the cello.

When the father saw Imre's talent, he decided to rent out his property and move the family to Pest to provide a better education for the children.

"He was given a job as the chief magistrate of the Pest-Pilis-Solt county, and their apartment was on the ground floor of András Fáy's house", recalls János Kéry, adding that Fáy, as a member of the most active Hungarian political circle of the reform era, was not only the founder of the First Hungarian Savings Bank of Pest but also a theatre organizer and stage director, taking the fate of Hungarian musical education and musical culture to heart.

András Fáy lived with the Székely family in his house in Pest and organized French-style salons and musical evenings in his holiday home in Fót, where the young Imre Székely also developed a confident stage routine. His audiences included prominent political and literary figures of the time, such as István Széchenyi, Lajos Kossuth, Ferenc Deák, Ferenc Kazinczy, Ferenc Kölcsey, Dániel Berzsenyi, Miklós Barabás, József Bajza, and István Ferenczy - just to name a few. Imre, meanwhile, became close friends with Fáy's son Gusztáv, who also played the piano, and they studied music and law together.

After graduating from the Academy of Law, Imre took part in the 1843-44 Hungarian Diet of Pozsony (today Bratislava, Slovakia) where his concerts were a great success, mainly performing pieces by Franz Liszt and his own works. It was then that he made up his mind to break with family and nobility traditions and devote his life to music. The decision to take up art was not uncommon at the time, but his father's attitude was all the more so, as he immediately supported his son's decision both morally and financially.

While he was still alive, he gave his son part of his inheritance to help him get further in his studies.

The investments of both the talented youngster and the "prodigal father" who supported him was a good decision. After graduating as a student of Ferenc Erkel in Pest, he travelled to Paris at the turn of 1846-47 with two friends, the aforementioned Gusztáv Fáy and the legendary violinist, Edé Reményi. Their talents quickly became known in the Parisian salon scene and they soon found themselves in Alexandre Dumas' salon, giving sold-out concerts, sometimes solo, sometimes together, organised by the Societe Philharmonique. János Kéry believes that Székely even heard Chopin live, who gave his last concert in the city in February 1848.

Queen Victoria and a children’s song

It was in Paris, that our hero lived through the Spring of Nations, for after the events of 15 March he became a member of the Hungarian delegation that went to the writer - Minister for Foreign Affairs, Lamartine, in the hope of French help. According to János Kéry, the Hungarian War of Independence and the death of his father prompted Imre Székely to return home, but after the revolution was crushed, he set off west again, this time to London. Paradoxically, while he was persecuted by Austrian politics for his involvement in Paris, the Hungarian fashion magazines reported on his highly successful London performances, the popularity of his music, and the fact that Queen Victoria herself listened to his concerts and even played his pieces.

The first piece of his series Hungarian Fantasy, originally titled Souvenir de ma patrie, was also written in London, and it elaborates and embellishes several Hungarian folk songs and art songs.

The most striking element of the melody to the modern ear is undoubtedly the double appearance of the popular children's song about a multicoloured calf: Boci, boci tarka.

"We will probably never know whether he was inspired by the children's song, or vice versa, i.e. whether the theme took on a life of its own as a result of the popularity of the work," says János Kéry, who believes that the three and a half years he spent in the British imperial capital were the high point of Imre Székely's career and perhaps also the key to his return home. He was already thinking about emigration when he came to Hungary for a few concerts in 1852, and the following year, thanks to a political détente towards him, he moved home and even took on the musical education of Archduke Albrecht's children.

Distinguished teacher of the National Music School

In 1853 he married Magdolna Halasy, the stepdaughter of the martyr of Arad, Vilmos Lázár, in whom he found a true spiritual companion. They had six children, but only two of them lived to adulthood. The two daughters, Ilona and Irén, were both very good pianists, and both became writers and literary translators, and composers. The family spent most of the year in Pest, but in the summer they retired to a farm near Tiszasüly. Imre Székely's last known residence between 1880 and 1886 was at 5 Szarka (today Zrínyi) Street, in the city centre, where he held music parties every Sunday. János Kéry also points out that while Imre Székely made house concerts a regular feature and was himself a concert artist, teaching gradually became the focus of his life.

After the court of the Archduke and many private pupils, the National Music School, the most prestigious institution of his time, invited him to become one of its teachers.

The National Music School (“Nemzeti Zenede”) was the predecessor of the Hungarian National Music Academy that was founded in the reform era. He taught a succession of enthusiastic and music-loving students, and together with Ede Bartai he started writing musical textbooks: he published a multi-volume collection of piano technique lessons, the School of the Sound Series (“Hangsorozati Iskola”), and his 15 Invetions (“15 Invenció”) series was made part of the piano curriculum. "It's interesting how much he has found himself in secondary teaching. Although he was a good friend and colleague of Franz Liszt and a former pupil of Ferenc Erkel, when they founded the National Music Academy, Székely did not follow them, remaining as a teacher in the Music School's class for outstanding talents," János Kéry points out, adding that he taught the poorer students for free.

He was of weak physique and his health deteriorated rapidly from the 1880s, but despite his persistent ill health, he remained an active teacher to the last. The obituaries following his death in 1887 reveal a modest artist who lived his vocation as a servant and an excellent teacher, remembered as the standard-bearer of Hungarian national music and a virtuoso performer who unashamedly deserved the praise of Franz Liszt. The authors of these texts were the students who learned from him how to play the piano in a heartwarming way, while their master regularly gave them the opportunity to participate in house and major concerts. On one occasion, he himself was honoured with a large-scale concert on his birthday: the 1879 Székely Feast included his own works as well as a tribute by his contemporaries.

Almost all of his memoirs highlight his modesty, his kind nature, his tireless work for Hungarian music, and his loving family background.

János Kéry believes that if we were to appreciate Imre Székely's life's work on the occasion of the 200th anniversary, we should probably highlight his lovable, quiet, and humble service, his debauchery-free life, his diligence in the second line behind the genius.

Asked about his plans as a monographer of Imre Székely for the bicentenary, he said that his long-term plans include a studio recording of his life's work, and in this commemorative year, he is trying to bring Imre Székely's name back to the memory of composers with a series of concerts in Hungary and abroad.