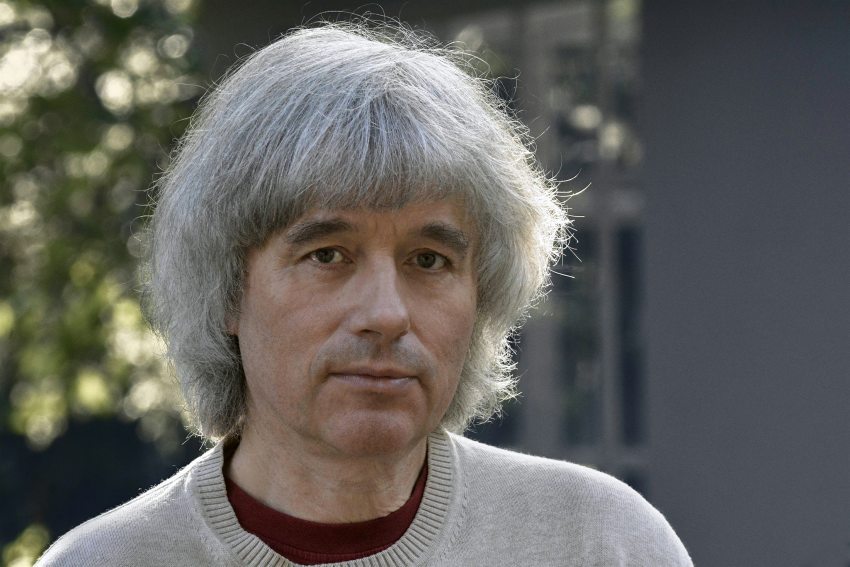

“I never longed to live abroad” – in conversation with Dezső Ránki, Artist of the Nation

Pianist Dezső Ránki is an outstanding figure in the world of music, both for his modesty and his talent. Last year, he was among eleven artists who had been awarded the highest state artistic honour, the National Artist of the Nation Award, though without the usual presentation ceremony. We also talked about the start of his career, his attitude as a performer, and, of course, the challenges of the present.

Today, the culture of artistic presentation and self-management is quite different from 30-40 years ago, although outstanding talent has long received special attention. How did you experience being a ‘wunderkind’?

“I believe that in the strict sense of the word, I was not a prodigy. I only started studying piano at the age of eight. It soon transpired that I had some talent for music but I attended normal schools all the way, but it is true that I did this faster by a few years than is usual, and I graduated at the age of 21. I started giving concerts in my 18th year when I won the international Schumann piano competition in Zwickau, just when I was admitted to the second class at the Academy of Music. That was a difficult academic year because I completed the first two classes of the academy in parallel, I attended the 4th class at grammar school as a private student, and I also took my school-leaving exams alongside ever more concert invitations.”

What family support did you get? Did anyone else play music in the family?

“My parents and grandparents were not musicians although both my grandfathers played the violin as amateurs. In the broader family, my father’s niece, Lili Ránki, was a piano teacher. However, everybody loved music, my father was a passionate collector of records and the radio was always switched on, which at that time played much more classical music. That's what I grew up in, and for example, at my grandmother's house in Csillaghegy - where I spent my summers - as a small child, passers-by would look on in amazement when I would stand at the gate and sing opera songs I had heard on the radio at the top of my lungs.”

The public perception is that artists who excel in the same genre are constantly competing against each other. How bothered, or encouraged, were you that you had several similarly highly talented contemporaries?

“The Liszt Academy was a very good place to be then. The lobby was always bustling with students and teachers, sitting at the cloakroom counter or at the cafeteria, talking and being lost in a debate. Unfortunately, in today's Academy of Music, perhaps for security reasons, but we search in vain for this atmosphere, it is irretrievably lost...

“We sat in concert every night and - I can honestly say - we were unenvious of each other's success when something went really well. When I heard that, it just made me want to work harder, to practice even more.”

Am I right in suspecting that it is as though the approach to music has changed since those days?

“The fundamental difference compared with today is that there was no computer or Internet, barely any TV, that is why music, musicians and concert life were held in higher esteem. Without any idealization and saying ‘those were the good old days’: yes, I felt the approach to music was more honest and more enthusiastic.”

How do you think the audience, the career pathway, the way of thinking for a young, beginner classical musician has changed?

“There is no doubt that the current situation is the outcome of a long process, but the ‘show yourself’ phenomenon has risen to a level that for me is nearly unbearable. It is only natural that everyone wants to stand out but frequently they want to achieve this with individualization. Music is the first to suffer from this approach. Spectacle dominates in today’s world and unfortunately, music is subordinate to this. Often, more attention is paid to external appearances than to professional skills. The young talents of today have an incomparably harder job because they have to produce artistically good work that meets the changing demands. The importance of management-self-management has become too great and, unfortunately, audiences can be fooled.

“The recipe: be confident, upbeat, direct and in tune, and you've got a winning case. But where's the music? With respect to the exception, of course.”

I suppose you, as parents, personally experienced all these difficulties with your son, Fülöp Ránki, who is also a pianist.

“Fülöp was never this type, he is passionately interested in music, making an impact for its own sake is as far from his personality as possible. He is completely remote from the influence of modern trends, they do not even touch him. He loves immersing himself in work and all additional ‘management’ activity is merely a burden for him. Luckily, he has a few very talented friends who think similarly, and are as demanding as he is, which is why I believe there is still hope in this modern shop-window world.”

You taught for several years. How did your educational and performance careers influence each other?

“In the ten years after graduating I taught at the Liszt Academy alongside Pál Kadosa, but I slowly came to the realization that with the busy travel and concerts there was simply not enough time and energy for this, so I slowly started backing out. When I was teaching, I was embarrassed not to prepare for the concerts, when I was practising or travelling, I felt guilty for the students. Nor is it any good for them if their teacher only gets to teach them every now and then. By the way, teaching did have an excellent effect on my own piano playing because the things I discovered during our joint work had to be presented, formulated and explained intensively and clearly. However, I gave up teaching fairly soon because of the reasons I have mentioned.”

You were invited abroad as a guest teacher several times. Why didn’t you ever accept these invitations?

“On the one hand, I never longed to live abroad and I am averse even to the periodic absences that go with such a position. Performing in concert occasionally involves long trips, for example, I was in Japan 15 times, mainly on 2-3-4-week tours, but this is really travelling and not sitting in one place. Anyway, at these times I quickly start counting the days left before I will be back home. On the other hand, I don’t feel I have either the commitment or the ability to do it really well.

“And I don't do ac-hoc courses because they are mostly public, and I think the teacher-student relationship is similar to the doctor-patient relationship: confidential and nobody else's business.”

Yes, this is once again an important core principle that goes against today’s ‘trends’. On the other hand, for decades you have been playing regularly with your wife, pianist Edit Klukon, and in recent years with your younger son, Fülöp. When family members play together, it involves the courageous commitment that something is revealed from these closest, most personal relationships. Am I right?

“The fact that we are each other’s partner not only in life but in music as well is one of the marvellous gifts of life. Of course, the two are interconnected, it wasn’t by accident that we met. We have been playing together regularly from the mid-1980s and we have given over 500 joint concerts. Generally, when we perform with Fülöp we not only do three-piano pieces, of which, unfortunately, there are only a few, but we have a programme in which Fülöp plays solo and we play a four-hand or two-piano.”

If Fülöp has a solo performance, who is more nervous of the two?

“I often notice that I almost prepare in my soul for Fülöp’s concerts as if I had to play and it is a great relief when I realize this is not the case. Fülöp has no reason to be worried, he prepares for concerts in an extremely thorough manner, the only thing I am keeping my fingers crossed for is that he has a good time. Whether he is worried or not I don’t know, but one doesn’t have to bother with this anyway. The music is important and he also knows that.”

Your older son, Soma, is an architect, but I assume that he, too, in all likelihood had the talent to have a career in music. Did he also play an instrument when he was a child? How does Soma connect to your music life?

“During his childhood, Soma learnt piano for a few years but then he totally turned his back on this lifestyle and gave up the instrument. We wanted him to study music because this cannot be replaced by anything else, it gives an extra something to everybody but of course, it would have been silly to force him, it didn’t even cross our minds to make a musician out of him against his wishes. Everybody has their own path; even as a child, he was always drawing cathedrals and other buildings. He hasn’t played the instrument for a long time but music is important for him, he has a good ear, good taste and he is extremely critical.”

How have you managed during the standstill caused by the pandemic?

“The spring halt caused catastrophe and existential crisis for many musicians and performers. Concerts were cancelled and it was not permitted to travel. For us, too, everything was basically cancelled, including tours of Spain and Japan; this latter may be substituted next spring if the situation allows. Irrespective of this, I myself had a great time at home in tranquillity, dealing with all those things that otherwise there is little time and energy for. I spent a lot of time in the garden, luckily I have enjoyed gardening since childhood, I never get fed up with it. We have a huge library, a vast number of books have been accumulated over 40 years so there is plenty to read. Besides this, time went with the family, with leisurely meals, drinking coffee, and it was possible to play the piano when I wanted, free from urgency and deadlines. The current, perhaps even more serious situation was less unexpected for us and we are confident that we will get through this in the foreseeable future.”

Could you mention some of your recent reading material?

“I’m hugely interested in Alan Walker’s book on the life of Chopin, which is exactly as well-researched, affectionate and still highly readable as his three-volume Liszt monography. Our friend Dénes Gulyás recently lent us his copy of Mario Vargas Llosa’s ‘Society of the Spectacle’, which we missed when it was published and I have been searching for recently in vain. The author points out the awkward processes of the modern world with very keen insight.”

Do you consider that there have been any positive consequences of this enforced closure?

“I'm not at all inclined to think of mystical connections, but such is the level of so-called "spin", pleasure-seeking, and the incredible amount of travel in the world that the beneficial side-effect of this serious, tragic epidemic for many, may be that people start to live calmer, more cautious, more restrained lives.

“It's OK to be quiet, because it gives us a chance to reflect. Don't be afraid of boredom, and don't rush around all the time, in general, spare the world around you."

“Before it’s too late. Of course, the uncertainties of existence, which affect many people these days, must pass.”

You have been an Artist of the Nation since 5 November 2020. What does this award mean to you?

“Since I have always lived at home, in Hungary, and not because there weren’t opportunities to leave, but because this is my home, I was especially delighted to receive this award. At such times I always have a strange feeling, I feel this as being almost as if it were not part of me. Besides the fact that this is not the goal, still, it is a huge joy if the decision-making bodies esteem and reward the work of decades.”

Beyond the official recognition, what were those events, feedback that you remember as success and ‘honours’?

“For me, the greatest reward is that after a concert, even if I am not satisfied, and basically I am never satisfied, I suspect from feedback that those who are close to me felt something of what I tried to play in the works.”

The interview was recorded in December 2020.