The revolutionary technician and the "adventurer" son of the Kazakh mother - the story of two heroes in Nyíregyháza in 1956

Although there was no violence or gunfight in Nyíregyháza in 1956, two local revolutionary leaders were executed in retaliation.

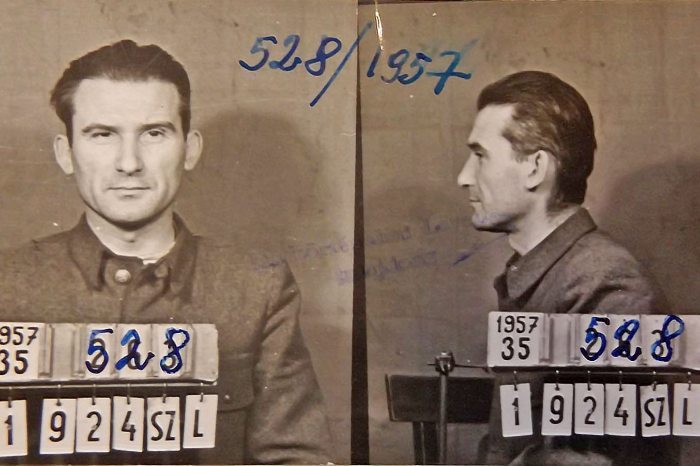

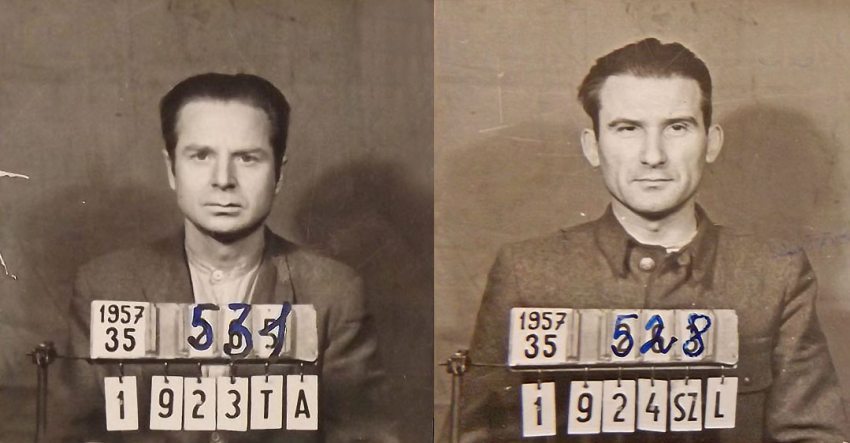

The fact that the vigilantes in Nyíregyháza have been curbed is mainly thanks to László Szilágyi. He was a bright boy born in a farming family in 1924. His parents enrolled him at the Kossuth Lajos Lutheran High School in Nyíregyháza, but the war prevented him from completing his studies. In November 1944, he fled from the Soviet troops on his bicycle to the West but was captured by the Arrow Cross and transported to Komárom, where he was conscripted as a soldier. After his release from Soviet captivity, he became an official at the Hungarian Investment Bank in the early 1950s. He married and had two children.

He got hardly any work because of his origin

The year 1950 had something else in store, however, as both his and his wife’s father was declared a kulak (i.e.: a prosperous peasant who owned land and could hire workers thus pursued by the Soviet regime) consequently László was dismissed from the bank, and his wife had to leave her job. Szilágyi was transferred to the Tiszamente Waterworks Construction Company at the end of 1951 but had to leave that position as well. He was able to find a job at the County Electricity Company, where he worked initially as a laborer and later as a design foreman. That’s where the revolution hit him.

On 26 October 1956, he went to work in the morning, but later he joined a demonstration in the town, which was led by a group of miners and workers from Miskolc, who arrived in trucks.

Szilágyi soon found himself in the thick of the action:

he became part of the delegation which, in the early afternoon, reached the printing press and managed to get 10,000 copies of the demands of the workers from Miskolc, with minor changes, printed, and then sent a telegram to Imre Nagy containing the support and their demands. Soon afterward, the provisional workers' council's steering committee was formed, and Szilágyi was elected chairman.

He wanted to prevent vigilantism

As a revolutionary leader, he tried to establish good relations with the local state and party organizations, but it soon became clear that no meaningful cooperation was possible. The first secretary of the county party committee told the party center in an intercepted telephone conversation that "a drunken gang had taken power in Nyíregyháza and were going to massacre the people". So on 28 October, they took control of the county. The next day, the final Nyíregyháza city workers' council and the county revolutionary national committee were formed, with Szilágyi elected as its leader.

László Szilágyi, as the county's number one leader, organised public services and ensured that wages were paid. He set up a national guard to prevent vigilantism. He was driven by a desire to control tempers when, in early November, he ordered the detention of the former head of the county party and the party secretary. He had similar considerations in mind when, at the meeting of the National Committee on 3 November, he proposed a clear message from the commander of the Soviet troops surrounding Nyíregyháza (they will not open fire, but if anyone attacks them, there will be a retaliatory strike): make "a decision that the radio and the loudspeaker [...] will announce every ten minutes what we have discussed with the Soviet command [...] so that the people should not do anything for their own good, should not initiate any provocation".

The Soviets were informed in writing that they would convict any person who, in spite of the agreement, would attack them.

Hanged instead of thanked

On 4 November, several former communist party leaders returned to power with the Soviet troops. The new public power body formed that day, the Workers' and Peasants' Revolutionary Committee, included the former leaders. The next day, the former county council president praised his work with the following words "I have no grudge against comrade Szilágyi, the city owes him nothing but thanks, and I will work with him." In spite of all this, the Soviets arrested Szilágyi that very night and took him to Ungvár, but released him a few weeks later.

The Hungarian authorities have proved less permissive. On 21 February 1957, he was arrested and tried in a military trial. During the trial, the investigating officers used excessive physical violence against him, consequently, on the first day of the trial, Szilágyi asked for his testimonies to be considered null and void.

On 13 December 1957, in his last speech, he asked in vain for his sentence to be imposed so that he could return to his family: he was found guilty and sentenced to death for the crime of initiating a conspiracy to overthrow the people's democratic state and two counts of violating personal freedom.

The most severe sentence was imposed despite the fact that there had been no deaths nor even serious atrocities in Nyíregyháza during the revolution.

This also caused serious problems for the new county leadership, as seen from the speech of András Benkei, the future first secretary of the county party committee and later Minister of the Interior, given on 18 April 1957: "... it is very difficult to work on agitation [...] because "nobody was hanged here, nobody was killed" - so the workers say in the villages [...] it is very difficult for honest workers to explain that it was a counter-revolution..."

However, the specific logic of the Kádár machinery of retaliation meant that the "criminal wavering" of the county could not go unpunished. By sentencing Szilágyi, a revolutionary leader of kulak origin, to death, the authorities set an example.

He was executed on the morning of 6 May in the courtyard of the Nyíregyháza County Prison. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the back of the Northern Cemetery in Nyíregyháza.

As a last wish, he wrote a farewell letter to his wife, but it was never delivered, despite the legal obligation. The letter was destroyed by the commander of Nyíregyháza Prison, Sub-Lieutenant Gábor Kató, because it contained "opinions that were in part unacceptable [sic!]".

The widow kept the fate of the head of the family a secret from the children for a long time. The youngest daughter, Erzsébet, learned from one of her schoolmates that her father's death was not due to illness. Many 'friends' turned away from the family during these years, while they also found it difficult to make a living. The widow was not employed anywhere, and if she was, there was always a 'well-wisher' who reminded the employer of the husband's identity, so that the elderly grandparents had to go to work. Even as a college student in the 1970s, Erzsébet felt discriminated against, because an examining teacher, after deliberately degrading her grade, told her she should be glad she was tolerated at all in the institution.

Born of the love between a Hungarian soldier who was taken prisoner of war and a Kazakh woman

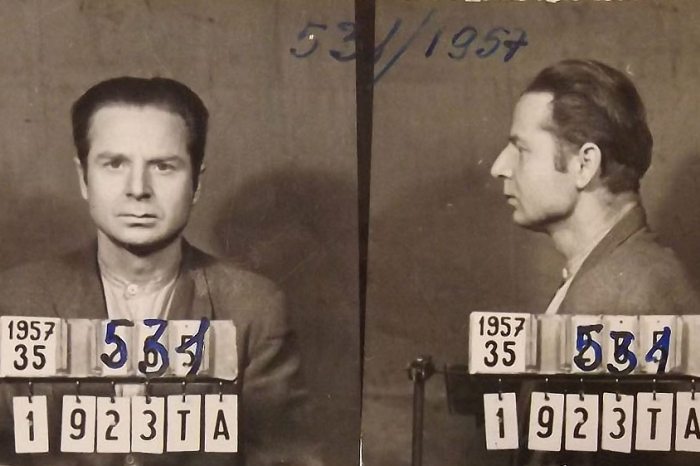

András Tomasovszky was born on 22 December 1923 in Almaty, in the Soviet Union (now Kazakhstan). His father, Mihály Tomasovszky, was a Russian prisoner of war in the First World War, who -despite being married in Hungary- married a young local woman and had three children. The family settled in Hungary in 1928, but as the father had not divorced his former wife, the Kazakh mother soon returned to the Soviet Union with her two children.

According to the family legend, little András stayed in Hungary because his father grabbed him off the train at the last moment.

After graduating from high school, András Tomasovszky worked on the family’s farm. In 1944 he married his step-cousin, Mária Bartha. They had three kids: Mária, Tibor and Ilona. In 1950, Tomasovsky was twice sentenced to six months in prison for endangering the public interest: first for unauthorized felling of trees, and then for failing to eradicate the Fall webworms’ caterpillars in his orchard. In the early 1950s, the father was listed as a kulak, his land was expropriated and a large family, also labeled kulaks, and the family of an AVO (communist secret police) officer was moved into his house. It was only through the goodwill of the former that the original owners were allowed to stay in the hall of their house. At that time, András Tomasovszky and his family were living in the shed of their house for a while.

From bystander to revolutionary

After their land was taken from them, Tomasovszky learned to be an electrician with his father and worked on the electrification of farms for the county electric company. Between January and December 1955, he was employed as an electrician at the Nyíregyháza Dairy Company and then worked for the County Construction Company in the same position.

The year 1956 brought major changes in his life, not only because of his new job but also because his wife died in July after a long illness.

It was after such events that 26 October, the day of the great demonstration in Nyíregyháza, arrived, during which Tomasovszky gradually moved from being a passive bystander to an active participant in the events.

Following the demolition of the Soviet heroic monument erected at the request of Marshal Malinovsky in 1945, he read out the demands of the people from Miskolc who had arrived in the city in the morning and played a primary role in catalyzing the events, which were adopted with minor changes and printed in 10000 copies at the local printing press. Tomasovszky took a leading role in the printing action, and later became the head of the committee that achieved the changeover of the army at Damjanich barracks. In the afternoon, he was elected a member of the five-man body set up as a temporary revolutionary leadership body. He was present when the demonstrators freed the prisoners from the prison, and in the late afternoon he tried to persuade the people demanding weapons at the barracks to see reason, but to no avail. The crowd was dispersed by the military opening fire, but there were no casualties.

On 29 October, the county national revolutionary committee was formed to formalise the actual power relations. Tomasovszky became a member of the narrowly-constituted Steering Committee, and President László Szilágyi put him in charge of the intelligence group. Its members were in constant phone contact with the villages on the Hungarian-Soviet border, informing them of the movements of Soviet troops. Once the information had been received, it was passed on to the revolutionary committees in the capital and the provinces.

He did not want to flee the country

After the suppression of the revolution, several people urged Tomasovsky to leave the country, but he refused to do so, claiming his innocence. On 13 November 1956, he was arrested, and on 9 January 1957, the Nyíregyháza District Court sentenced him to three months imprisonment for concealing weapons. On 23 April he was arrested again and tried as a third defendant in the trial of László Szilágyi and his associates.

Although the family status of several of the defendants in the trial was considered a mitigating circumstance, Tomasovszky asked in vain for a sentence that his three children "should not be completely orphaned".

The military court did not take paternity into account for him or for Szilágyi, who had two children.

On 13 December 1957, Tomasovsky was found guilty of the crime of initiating a conspiracy to overthrow the people's democratic state and sentenced to death.

The 1957 propaganda publication, known as the County White Book, presented the events in Nyíregyháza as part of a country-wide "counter-revolutionary" action plan. (It is characteristic that in the publication Tomasovszky was referred to, among other things, as "the adventurer son of the kulak commissioner"). On this basis, the verdict is full of unfounded allegations aimed at smearing the revolutionary leaders, such as that "all their actions were aimed at restoring the capitalist, landholder system".

In his last speech at the appeal hearing on April 28, 1958, Tomasovszky drew the court's attention to a serious procedural "omission" ("I could have proved my case with witnesses, my witnesses were not examined"), but this was not enough to get the Supreme Court to reduce his sentence. His execution took place on 6 May in the courtyard of Nyíregyháza County Prison.

No mercy to ancestors or descendants

His father was dismissed from his job after the revolution was crushed. He could only find work as a digger, and even at the age of 70, he worked to support his wife and granddaughter Mária, who they took in at her father's request. Mária Tomasovszky recalls that after the execution, she "stopped being a child". Her father was not mentioned at all in the family until the change of regime, because of the fear that was ingrained in them, but her daughter thought of him in pain. “I lived through [my father] standing up under the gallows a hundred times. [...] Until I knew my husband, [...] it was a very rare night when I didn't fall asleep crying." Even though she passed the entrance exam, she was not admitted to the agricultural high school after the head of the institution was "informed” by the “authorities”.

Although she had completed a course in shorthand and typing, she was only offered a job as a cleaner in a ceramics factory, where she was constantly humiliated because of her family's past.

The constant mental ordeal was only somewhat alleviated when a job offer took her to the capital, where she knew no one but her host relatives.

The remains of Tomasovszky and Szilágyi were recovered at the dawn of the regime change, and on 6 October 1989, the two martyrs were given a dignified burial. The death sentences were declared null and void by the military court in Debrecen in February 1990. In 1991 they were both made honorary citizens of the city and in the same year, a memorial burial place was established for them in the Northern Cemetery.

This article was produced thanks to the National Remembrance Committee, based on the work of historian Gergely Czókos.