Blessed are the cheese makers? – The Hungarian Schoenstatt Movement seeks to respond to the problem of the families in crisis

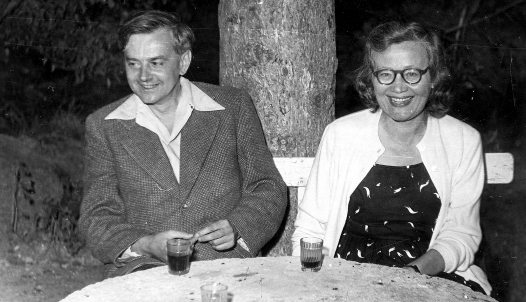

When I once searched for the smallest settlements in Hungary, I found Óbudavár, at the entrance to the Nivegy Valley. From there, the path quickly led me to Bálint Szabó, who, after graduating from university with a degree in Hungarian studies, started to raise livestock and make cheese in the village. Today, in addition to making cheeses with the flavours of the Benedictine herb garden, he and his wife host the local Schoenstatt centre for pilgrims.

Are cheese-makers really blessed? And how do those making a fresh start in the countryside in the spring cope with the autumn mud? Interview by Andrea Csongor.

It's a small village, but it has a unified, clean style, it seems to represent tradition and simple values.

There are about thirty of us living here, the whole village consists of twenty or thirty houses and a row of wine cellars. The style has become more and more uniform over the years. It used to be a somewhat patchwork settlement (apologies to the residents of the time), now when they renovate a house they pay attention to the traditional style. All the owners feel this desire, it is not something we have collectively agreed on. An archaeologist and a graphic artist also live in the village, the homes have a good atmosphere.

I have noticed that a common element is the embossed year on the facades and the crowstepped gable. When I walk around, I feel that there is a kind of spirit to the place.

The plaster decoration is usually the year of construction, here the houses are built on simple rectangular foundations with delicate decoration. We don't have the adjacent porches, mansards, balconies, or elaborate roofs. In the old days, if someone wanted to stand out, they would put a bit more plaster decoration on the facade, or put a taller crowstepped gable, so that the house would look bigger from the outside than its actual area. I hope that the local Schönstatt movement also adds to the creativity of the spirituality.

You're not from this place originally, but rather a kind of "newcomer ". Did you have to struggle for the status?

My wife was three when she moved here with her parents - who were warmly welcomed by the village - and she grew up here, so I had a connection to the land through her from the beginning.

What kind of life were you preparing for before you met Anna?

Since I was 16, I wanted to live in a village, even though I am originally from Pest. My life with Anna was not the classic story of being tired of the city or wanting new challenges, so we moved to the countryside.

I studied Hungarian and comparative literature, and so did my wife, and even before university, we were looking for the possibility of a life in the countryside.

When we graduated – which was a long time coming – we made our vision a reality.

Two young intellectuals studying in Pest, who had not even begun their lives in the capital... How did you manage to establish the country life you wanted?

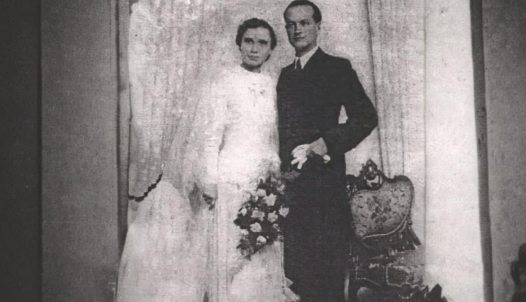

Anna and I got married before even starting our university studies, and then we started to have children and had to earn money. We didn't start our family in the classical order, but first we had children, then we earned money, then we bought a house, and then we went to university. The idea was that after graduation I would teach while farming. I had an arranged job in the nearby town of Ajka, where I would have started teaching in September, so in the summer of 2006 we moved to Óbudavár, but in August the school told me that they had found another way and did not need me.

On one of the T-shirts in the guest house there is a quote: 'Faith in Providence requires a constant death leap'. The trust you had in the presence of the other shore was there, even as fog shrouded the other side. How did you move on?

We took several gap-years during our studies at the university and went out to Vienna to work, thus creating the financial basis. Anna worked in a tobacconist's and I was a bicycle messenger. When we bought the house, there was still a lot of work to be done, because in the eighties the house, which was originally a historical building, had been demolished to the ground and rebuilt in a not-very-nice way. In the meantime, our children were born in a row: Jakab, Sámuel, Jónás, and here in Óbudavár Izsák, Magdaléna (Lenka) and Támár.

We moved here with three children, just in time for the eldest to start school.

You were going to teach in Ajka, but this opportunity did not materialize. It must have been a difficult moment.

It didn't feel good... But in Monostorapáti, there was a Swiss foundation that ran a programme for difficult children, the idea being to break them out of the dysfunctional cycle they had been in. In this beautiful Hungarian village, they found themselves in a completely different environment, helping around the animals in a farm. I got a job there, worked with the children, talked to them, took care of the animals together, and here they got a chance to sort their lives out. It was a difficult genre, but it was there that I met a farmer who kept sheep and got some useful ideas for farming from him. I had no previous experience of this, but I read books, asked questions and got answers to my questions.

An intellectual family with three children, and you've suddenly decided you'd rather be farming...

When I came up with the idea at home, I had to promise never to bring manure into our home (let's not ask if I've kept my promise). I started small, with three goats. It wasn't a firm decision, more like a lot of little emergencies and choices, for example, if there was a month or two of no money because there was no work at the children's centre, I was prepared to make the switch. I loved working there, but there were periods of uncertainty. When the foundation closed down, I used my father-in-law's land, and later we had ten goats, but there was a point when we had seventy.

When the goats didn't give milk for some reason, even though my customers were counting on me, and I didn't have anything to serve them with, I had a cow.

Step by step, you have made the dream a reality.

People who come to the countryside expecting a stress-free rural life are usually disappointed, but there are different ways to react to disappointment. They are disappointed because life here is highly exposed to the weather and countless variables, with a lot of work and vulnerability. Those who arrive in the spring are surprised to find that they can spend weeks in the mud in the autumn.

There is also a retreat center and a shrine in the village.

The Apostolic Movement of Schoenstatt is a Catholic movement that started in Germany, which began to gain ground in Hungary in the 1980s, and has its centre here. It strives for holiness in everyday life, a covenant of love with Mary and a practical faith in providence. From small, everyday events to historic turning points, we are constantly searching for the answer to what Providence is telling us. From a structural point of view, the uniqueness of the movement is that it is made up of individual small communities, and it seeks to address each community in its own uniqueness and according to its phase in life. In our community, the family movement is the strongest, we are bound to the movement as a couple, as a family. In Óbudavár we created the Marriage Path, a fifteen-station walking trail, the stations representing the different stages and difficulties of marriage. The stations encourage people to stop and talk.

What inspired this community to create a movement within a Catholic framework? Is there a need for a more practical relationship with God behind it?

Why are there monastic orders? When movements within the Catholic Church have been created, they have always been in response to a particular issue of the time. The Benedictine Order was a response to the harmony between work and religion, to the question of leaving the world: this was an important response at the time, and the Benedictines became the bearers of the culture of the time. The age of St. Francis called for another answer, a stronger experience of dependence on God through poverty, a more direct relationship with nature. The Jesuits live a radical way of obedience. Through the ages, God is always trying to gift the Church and, through her, the world. Schoenstatt is one such gift.

What question was this movement the answer to?

The theoretical and practical breakdown of families.

Today, we see that many families are falling apart because they simply fail to stick together, but there is also a theoretical attack on families.

Anna's parents started the movement back in 1983. Later, more and more families joined and slowly the centre was built on the outskirts of the village. Living with the village was not always without conflict, but today we have a peaceful relationship. Today, families come to us for retreats throughout the summer and almost every weekend and more than a hundred families support the work here. This is what I was called to do today and here, Anna and I have become the managers of the Centre.