Sándor Lezsák: “We didn’t listen to the news, rather the NEWS happened in the garden of our home”

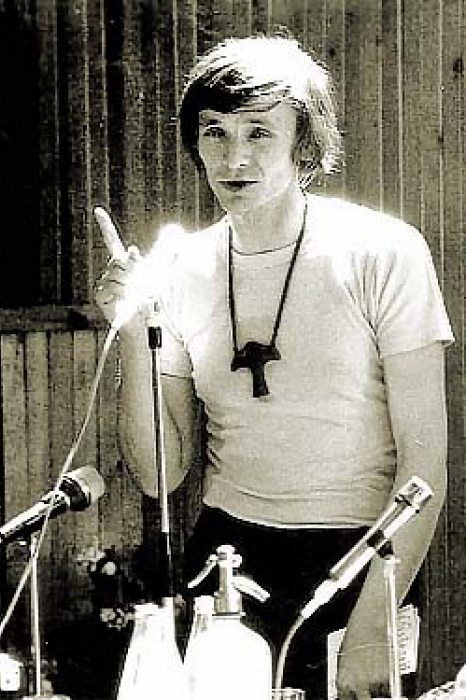

Anyone who has followed public affairs in Hungary over the past more than 30 years will certainly be familiar with the name and the role of Sándor Lezsák, especially in the intellectual and practical establishment of the process of the change of regime. In the three decades since then, the József Attila Prize-winning poet and teacher also played his part in parliamentary work while never seeking out the limelight. He has always been motivated by noble causes, including when, in 1987, the Hungarian Democratic Forum, the strongest government party of the first freely elected national assembly after the change of system, was formed in the garden of his home. We asked the current deputy speak of Parliament mainly about this period.

How do you recall the mood of the years preceding the change of regime? Did you ever think that the transformation could come about in your lifetime?

“I had just turned seven years old when, at dawn on the 4 November 1956, instead of trams Soviet tanks rumbled through Pest, on the Grand Boulevard. In my mind, everything may have started then. I was imbued with my parents' alarm and restlessness. Twelve years later, it was Prague and then the Poles. In other words: Corvin Lane – Wenceslas Square – Gdansk shipyard. For me, the message of these three symbolic sites is that there is hope for change, they prove that sooner or later movements will have their consequences that create new situations, because – this is a very simple truth – the power of no empire can last forever.”

What were the signs of the impending collapse of the Kádár regime – had change become inevitable or did it have to be forced?

“In my estimation, the change of regime process started on 23 October 1956.

“The communist system was swept away by crowds numbering hundreds of thousands. It was revived with the help of Soviet tanks. The dictatorial system kept itself alive for decades under the hand of the Soviet empire and secret service, with foreign loans and by maintaining a constant state of readiness for threats. However, we believed in the possibility of change, our faith was strengthened, encouraged by the Polish pope, the Central-Eastern European, mainly Polish underground movement, and national emigration.

“All this was preceded by much local mobilization, relations forming into freedom circles, which were established around specific cultural houses, libraries, church congregations, writers or journals, for example, Tiszatáj in Szeged. All these engaged in politics at the limits of tolerance and prohibition, but we considered our job to be to stretch these boundaries. The opportunity for change was accelerated by major political events. The senile decay of the Soviet system, Gorbachev’s perestroika, and last but not least the Polish Solidarity movement also reinforced us.”

What sort of situation did you live through from the middle of the 1960s onwards, which prompted you personally to become one of the shapers of processes?

“I was consciously aware even at the age of 10 that my grandparents living in Nyírség did not join the cooperative, but the orchard was taken away from them and the cherry trees were felled. When in 1969 I moved to Lakitelek after the reality of the Pest tenements and the small village in Nyírség, the Szikra village school, the healthy instinct for life of families created situations which developed in me organization skills for better lifestyles.”

Did you feel fear or doubt, and if so, why, or were you sure of yourself?

“I was always organizing. In 1979, at the meeting of young writers at Lakitelek, Gyula Illyés taught us to handle doubt: although we could doubt, it was forbidden to fall into despair. He taught us to overcome humiliating events, otherwise one would drown in the stark everyday reality.

“One has to find the path leading from the impossible to the possible because an insoluble situation ruins a person. A cheerful outlook on life, however, gives strength.

“Naturally, this does not mean that any of us were laughing through these years. We faced tough dilemmas about where to go next. This is what I experienced when my situation in Lakitelek became increasingly untenable. Once, József Ratkó called me and told me to go to Nagykálló where a rectory had become vacant. I would have a flat and a job there. Only the person of Ratkó – he worked in the district library – made me think when I pondered how to move on. But that, too, only lasted for a moment. It wouldn’t have been a heroic act had I decided to escape. There was in me a sense of ‘for all that!’, as I also didn’t go in the direction of making samizdat. I am not ready to go underground in my own homeland, in Hungary! What do they think! It was a good feeling that those I followed acted similarly. The founders of MDF, the political golden team: Zoltán Bíró, Sándor Csoóri, István Csurka, Gyula Fekete, Lajos Für, Csaba Kiss Gy. They represented models and if one goes back in history one will find many things that help in difficult situations of life.

“According to an oft quoted statement of István Bibó, a democrat is a person who is not frightened. It is easy to say this but I admit that I still feel a shiver, not from fear but from concern and responsibility when I think about the first Lakitelek meeting.

“When, a few minutes after quarter to nine in the evening, Gyula Fekete closed the meeting and we said goodbye to the last guests, the pavilion was empty and suddenly there was a great silence. It felt almost like a weight. I stayed there with the family and all the joy and tension of the day broke over me. I kept on thinking about not messing up anything. I was afraid that the police might take it away from me. I felt that there was no escaping my fate. I had to organize. Neither my wife Gabriella nor my close family ever held me back. The community organized around me grew continuously.”

What are your best personal memories from this period: what do you most like looking back on and what are you most proud of?

“Beside the birth of our three children, the opening of the Lakitelek meeting in 1987. I quoted László Nagy: ‘We bear red and mourning of revolutions cut at the throat. Another blow to the throat can be fatal.’ As I read out this line, I felt that it weighed a ton. The nearly 170 people could also sense that we were not listening to the news but here, in the garden of our home on the edge of the village, in a hired wedding tent, NEWS was happening.”

Is there anything that gives you mixed feelings, about which you feel sorry or disappointed?

“In the period after the free elections in 1990, efforts were made to heal those serious wounds caused by the several decades of state-party rule. There was little sense of achievement and more failures. I consider the biggest factor to be that we did not succeed in winning a two-thirds parliamentary majority at the first free elections so we had no opportunity for radical change.

“To sum up: we could manage this, which is not much, nor is it little, either, on a historical scale.

“For me, the regime changing historical moment was in April 2011, when we approved the Fundamental Law of Hungary, the new constitution, with a two-thirds majority. As far as I am concerned, this is a national programme and its defining part was also present in the declaration of the Lakitelek meeting in 1987.”

Have you been able to experience and enjoy as a private individual these fate-changing years or does your role require the mindset of a politician from beginning to end?

“Today, I still don’t know what this concept means: mindset of a politician. There are no problems, there are only tasks, we generally say. Since I have been aware, tasks have piled up in front of me. There are tasks which must be solved in the family, as a father, or now, as a grandfather, some in public life, as a member of parliament, some in the Hungarikum Liget being built in Lakitelek, that is, in the People’s College (Népfőiskola), and some I am able to resolve only in writing, in poetry or drama.”

What would be the message to your young, regime-changing self from the perspective of 30 years – and what sort of message would the then young Sándor Lezsák send to today’s generation?

“My mother said when she was 90: if I had known that I would live so long, I would have taken greater care of my health. I could give no better advice than this during an epidemic.”

The article was written on the occasion of the anniversary of Change of Regime 30 with the support of the National Cooperation Fund.