If we don't want to become America, where liberal democracy collapses into Marxism... - Israeli philosopher Yoram Hazony on the future of conservative thinking

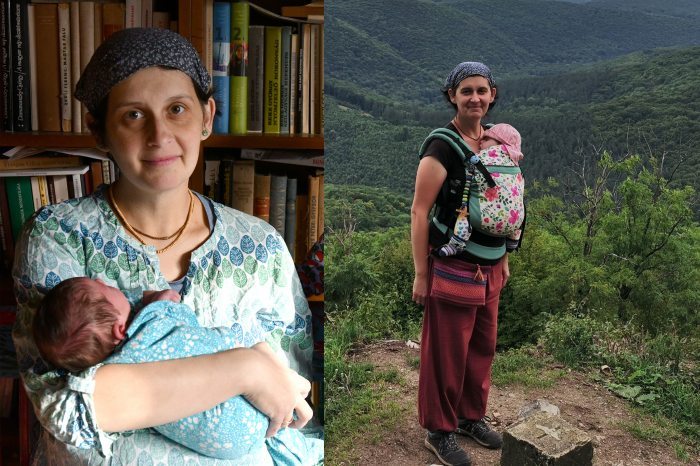

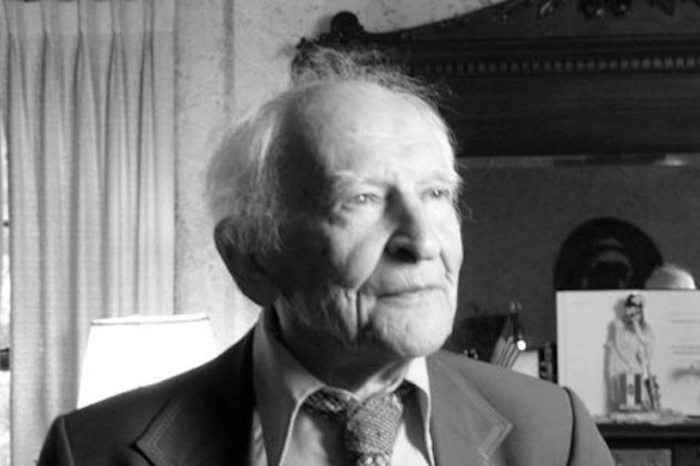

"Conservatism: Return to the Basics" was the title of a lecture given in Budapest by Yoram Hazony, head of the Herzl Institute in Jerusalem. The Israeli philosopher, biblical scholar, and political theorist came to Hungary at the invitation of the Mathias Corvinus Collegium. His thoughts are quoted below.

European and American culture

"One of the main features of European culture today is very similar to that of the US. After the Second World War, liberalism - by which I mean a worldview that puts individual freedom, liberty, and equality above all else - became dominant on both continents. This dominance in America and in most of Europe has been almost unchallenged ever since, but in the last few years, we seem to have witnessed a change. After Trump and Brexit, several democratic countries seem to have moved towards a national conservatism that was previously unknown. I think liberalism has had some achievements, but in many ways, it has been destructive. At the same time, I think that the return to the idea of the nation, the idea of religion and the traditions of each nation is remarkable and crucial."

New Marxism in America

"In 2020, liberalism in the US has essentially collapsed. Liberal institutions such as the New York Times or Princeton University, Hollywood, and many others have moved in what I call New Marxism.

It is no longer liberalism because it not only emphasizes individual freedom, but it deliberately tries to overthrow the traditions of Western countries. I am also talking about the church, the nation, the family, and even the difference between men and women.

This is what is happening now in English-speaking countries. But when I look at parts of Europe, I also see hope, because it seems that certain countries are more willing to fight for their national independence, for their traditions, than America is. We are in the strange position where small countries like Hungary or Israel can be an inspiration to many American conservatives, who can now say 'maybe we have something to learn from them."

Liberalism and Conservativism in private life

"Liberalism is not wrong in the way it describes how the economy works. The economy is based on individuals and companies that produce and trade, buy and sell. It is a way for people to succeed in a narrow field. The problem with liberalism is when it steps outside the economic sphere and starts to replace the family, the nation, the church, and causes damage. If a man wants to marry a woman, what kind of relationship is actually being built? Is it completely free? Is it like a business in the marketplace? If we get married at twenty-two or twenty-four and remain so perhaps for the rest of our lives, what is the right framework for me to understand the relationship?

As long as she seems to be the best for me and I seem to be the best for her, should we stay together? Then I should switch to someone better, because why spend time with someone who is not the best for me? This is a liberal perspective to which a conservative says no.

Our most important relationships are the ones that, when they become difficult, when they go into crisis, when they hurt, we say to them: we stay. The opposite of the market approach. When you don't like your job, you quit, you can go look for a better job, but that's not what we do in a marriage. We build that for a lifetime. It includes the good and the bad, the successes, but also times of extreme pain. All marriages succeed with pain, not from the absence of pain - when husband and wife say this is worth doing for her/him, we will find a way through the pain despite the difficulty. The same is true of raising children. The relationship is permanent, the responsibility never goes away. Not like in the market."

On the nation

"A nation is also much more like a family than a market. Sometimes the wrong people run the country, but it's still your country. Sometimes they interpret your traditions well to create beautiful things, other times they interpret them badly and do a lot of harm. But even then you don't run away and look for another nation for yourself instead. If you bring market principles into your relationships or the relationship between citizens, the family and the nation cease to exist. We have seen this over the last 30-40 years. We have become people who think that the only thing they need is to do what feels good at the moment, without regard for the past or the future."

The impact of world wars

"During the Second World War, the nations of the world struggled against racial imperialism, the Nazi Party theory that left no room for independent nations, religion, individual freedom. No room for the market. It was a trauma for most nations of the world, and many leaders came out of the Second World War determined that it would never happen again. The two world wars destroyed the world as we know it, and it is a noble aim that it should never happen again. But it was also said: the problem with German Nazism was that it did not treat people equally, it did not consider Jews equal to other Germans. Equality, individual freedom, if you enforce it hard enough, will eliminate all fascism, communism, imperialism from the world. It is a utopian theory, though it has done well in the name of liberalism. Americans stopped persecuting blacks in the south, abolished race laws. That was right, but it was wrong to say that just because the Nazis did not treat Jews and Germans equally, or because Americans did not treat blacks and whites equally, everyone should now be treated equally. Men and women too. They say if you are conservative, if you don't want perfect equality, you are like a Nazi. The power of liberalism is that every time you say something against equality, against individual rights, the trauma kicks in and you are treated like a Nazi. But you can't treat everyone completely equally. Take sport: some people believe that athletic competitions should not be held separately for women but together with men, and those who say this believe that women would participate..."

Liberal versus Conservative Democracy

"The liberal believes that freedom, rather than tradition, will solve all the world's problems. It is hostile to the idea that traditions inherited from our parents and grandparents give us strength and direction.

The job of conservatives is to deepen the connection with national, religious traditions, and the job of liberals is to worry about freedom.

The term liberal democracy is a very recent one: it was invented in the 1920s and 1930s and only became prevalent in the 1980s and 1990s. However, liberals like to pretend that it is an ancient term. By contrast, conservative democracy today is Hungary or Israel, or even Britain. Britain has a king, a queen, an established church - its society is liberal but its institutions are conservative. America was also a conservative democracy until the 1950s, with a public life based on Christianity, traditional laws, language, family structure, morals. It was only in the 1980s that they began to call themselves liberal democracies, as if this were the only legitimate form of government at the pinnacle of world history. They said there were three ways of approaching politics: communism, Nazism, liberal democracy. So if you don't want to be a communist or a Nazi, you have to be a liberal democrat. But you are wrong, there is at least a fourth way: it is conservative democracy. A country that is interested in preserving the freedom of individuals, but its public life is traditional."

The solution is in us

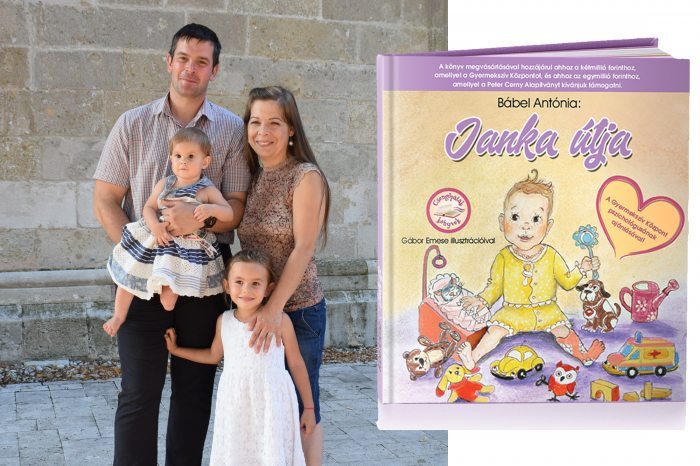

"‘In the end, what really determines what happens is whether you personally are a conservative, whether you personally lead a conservative life, building it on the love of your family, your congregation, your nation. Your congregation is not just your faith, it's a big family where you meet real traditions, older people, and you see how marriages work, parents, grandparents. You begin to absorb knowledge and wisdom. The Bible is just part of a way of life that protects you and gives you new freedoms. A young couple can learn from older members what it means to start a family, to belong to a nation. It is also about the balance of freedom and responsibility.

If we don't want to become America, where liberal democracy collapses into Marxism, we need to fill the space with something else: it can be a conservative democracy, where Christianity is the dominant culture.

If you change your life, you will affect everyone around you. You don't have to believe in God to go to church, you just have to believe that you want something different from what happened to America and Britain. If you want to be a wise person, the rabbi says spend your time with wise people. If you don't take the first step, you will remain part of the problem, even though you have the power to fix tomorrow. True, beyond a certain point, your life is not up to you. Religious people believe: our lives are in God's hands, but we can make choices. But ultimately, you don't decide what happens. Never in my life did I think I would be sitting here talking to Hungarians about national conservatism - it was not part of my plan, part of my dream, but it was part of God's plan. And if we are a little flexible sometimes, we can become something we never thought we could be."