Death-defying Hungarian courage in the headlines – how the international press covered the 1956 uprising

None of the milestones in the history of our country has attracted as much interest in the world press as the 1956 Revolution and War of Independence. As Henry Kissinger, former US Secretary of State put it, "It was the Hungarians who hit the first brick out of the Berlin Wall". The courage of our parents and grandparents 68 years ago was significant not only locally, but also in world politics, which is why international public opinion followed the Hungarian David's fight against the Soviet Goliath. About 150 foreign journalists and correspondents who came to Hungary made it possible.

The true face of communism – In the shadow of Suez

In the two months following the outbreak of the revolution, Hungary's name appeared on the front page of The New York Times nearly twenty times – more than before and since then. This also means that the public's perception of Hungary abroad has been shaped by the actions of our heroes in 1956 more than by anything else in recent history. The 1948 secession of Tito's Yugoslav socialism from the Soviet Union, the 1953 East German uprising, and the 1956 'Polish October' did not offer the world as much hope for the end of communism as the awakening of the Hungarians. However, the West, after Stalin's death, had hoped in vain that the Soviet Union might take a more democratic direction, the brutal crushing of the Hungarian revolution dashed those hopes.

As The New York Times aptly wrote at the time, "Communism showed its true face in Budapest".

But the Western world's attention was then more occupied by the crisis in Suez that erupted on 29 October. The British conservative daily The Daily Telegraph said that if the British prime minister had not landed in Egypt, "world public opinion would have forced the Soviet Union to withdraw from Hungary". Western media interests wanted the Hungarian revolution to be successful, as this could have led to the Soviet Union's influence being reduced. The intervention of the British and French in Suez, however, was not a good thing, because on the one hand, it let the Hungarian revolutionaries down for a war that was more important to them, and on the other hand it gave the Soviet power a reference point for an armed presence in Hungary. The German newspaper Münchener Merkur wrote: "There is a huge difference between Hungary and Suez. This conflict in the Middle East is a mixture of fanaticism, conflict of interest and power politics, with neither party being morally superior to the other. In Hungary, however, there was a case of child murder."

And the French conservative Le Figaro lamented, "It is intolerable that the West stands idly by and watches Hungary being drowned in blood."

Distorted news but spreading the Hungarian spirit

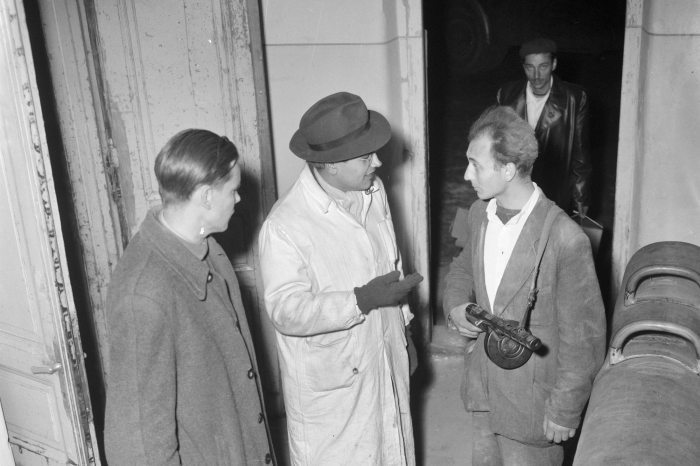

At the time of the revolution, there were around 150 foreign journalists in Hungary, although many arrived after the revolution had broken out, as obtaining visas and entry permits was difficult. Reporting was difficult to get through to the foreign press, with many journalists telephoning from embassies because of the unreliability of the Hungarian telegraph network. The Washington Post reported that "almost all information comes through Vienna". The journalists were competing to gather news, but the field and their inability to speak Hungarian made their job difficult. When many of them were redirected to Egypt because of the Suez crisis, the number of reports on the Hungarian situation dropped. Fake news also spread: when the Stalin statue was pulled down, the authorities did not open fire on the protesters, or hang them from lampposts or throw them from balconies, as the Italian Il Tempo and The Washington Post reported. The death toll in the revolution was not in the tens of thousands, as The New York Times reported since 2 500 people died in the weeks of the uprising and 229 were sentenced to death during the reprisals.

Budapest was not bombed by Soviet planes, nor was Ferenc Puskás killed in the fighting, as Paris Match reported.

Despite their less-than-accurate information, foreign correspondents played a key role in spreading the word of the Hungarian Revolution. Without the international press, mass demonstrations and sympathy rallies would hardly have been organized worldwide, as this was the only way to ensure that the brutal repression imposed by the Soviet Union's leaders would cause a huge shock in foreign public opinion. The '56 revolution had an impact on the entire global political scene during the Cold War, making the Hungarian stand a symbol of the desire for freedom and the struggle against oppression. Foreign press workers, even at the risk of their own safety, maintained the truth in their reports that the revolution was a swift, spontaneous action organized from below. Jean-Pierre Pedrazzini, a journalist for Paris Match, gave his life for Budapest: he was shot 14 times in Republic Square and died of his wounds. Others survived the street fighting with head wounds. Later, they also dealt with the Hungarian refugee issue: the number of Hungarians who fled to other countries exceeded 200,000, and 37,000 Hungarians arrived in the United States.

The communist countries of Eastern Europe followed Moscow's propaganda in their reports: according to Pravda, the events were a "vile, Western-backed fascist coup attempt ".

From New York to Seoul, everyone was watching us

The German Spiegel said, "The revolution was obviously spontaneous" and went on to say, "If there is an uprising that simply springs from the heart and the most instinctive passions, then the Hungarian October Revolution is one." The New York Times described János Kádár as "a Communist politician who knew every trick of politics" and wrote of the revolution on 27 October: "The Hungarian people have won the admiration of the free citizens of the world: they have stood this hard test. [...] The heroes of Budapest are fighting not only for their own freedom, but also for the freedom of New York, Paris, Delhi, Rio de Janeiro, Bandung and Tokyo." The Times argued for "a reduction in Soviet military and economic influence, a higher standard of living, higher wages and pensions, decent housing and not least wider political freedoms" for our country.

Le Figaro reported on the 25 October massacre: "Everything here is just so horrible, young people and children with blood-soaked bandages on their arms and foreheads fighting against the tanks and artillery, with their machine guns and grenades dating back to Noah's flood." Il Tempo also drew attention to the losses suffered by the Soviets: "Never in war have I seen such devastation in tanks as the Soviet tanks here. One of them, which I saw on the boulevard, standing on the scorched lawn of a flowerbed pavement, had its turret regularly blown off by an artillery hit, the punctured frame opening like a milk carton."

In a special 100-page (!) issue devoted to the events in Hungary, LIFE magazine pointed out that "it is difficult to describe in words how this remote little country, the size of the state of Indiana, with a population the size of New York City, found the death-defying courage to take up the gauntlet against the Soviet Union".

The official newspaper of the Italian Communist Party, l'Unità, on the other hand, described the revolutionaries as vandals, provocateurs, and even fascists, acting out of what it saw as nostalgia for the Horthy regime, and interpreted the demonstration as a counter-revolution, and considered the Soviets' entry as justified. In 1956, former Italian President Giorgio Napolitano condemned the Hungarians as communists, however, in 2006, in a not insignificant turn of events, he was the guest of honour at the invitation of President László Sólyom in Hungary at our 1956 commemorations.

There were also interesting reactions from Asia. India pursued a policy of balance and neutrality on the Hungarian question and did not support intervention from any direction. South Korean President Li Sin Man, on the other hand, hoped that the wave of bold action by the Hungarians would even reach North Korea, where it could wash away Kim Ir Sen's regime. "Hungarian people, you are phoenix birds that never die! Glory be upon you!" – enthused the Seoul newspaper Chosun Ilbo, but ultimately it was not Kim Ir Sen's regime but that of Li Sin Man that was swept away by the Korean student uprising in 1960.

What did the spotlight bring out?

After the defeat of the War of Independence, the editorial staff of several Western newspapers thought that the fighting was not over. The New York Herald Tribune expected that "János Kádár and the Soviet tanks cannot hope to revive Hungarian economic life. Under present conditions, it seems certain that the country will soon have two hundred thousand unemployed. Unemployment could easily lead to another violent outbreak of revolution." Henry Kissinger, on the failure of American intervention, said: "What scared the United States away from intervention was not the threat of our defeat, but our unwillingness to pay the price of victory."

"The Hungarian Revolution had already been defeated for Washington before it had even broken out."

What is it that made 1956 so significant in the eyes of the world – in comparison to earlier and later events of equal importance to us? The 1848-49 Revolution and War of Independence were part of an extensive process on the continent, as revolutions were raging throughout Europe, so we were not the focal point in Europe, let alone in the whole world. And the 1989 transition gave the spotlight to the Polish Solidarity movement and Lech Walesa, plus the West's greatest recognition, the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1956, however, Hungary – along with Suez – was the focus of the world's attention, and international public opinion still sees our fight for freedom as the spark that ignited the fire that later burned communism to the ground. The New York Times summarized the events before the Soviet troops withdrew, "The brave Hungarian students, workers, and farmers have been mocking our fears and our little faith this past week. [...] The heroism and courage of the past few days have not been in vain. This courage is a credit to those whose ancestors once fought alongside Lajos Kossuth."