„Even as a child I vowed to find their graves” – A Hungarian researching the fate of the victims of the Beneš decrees

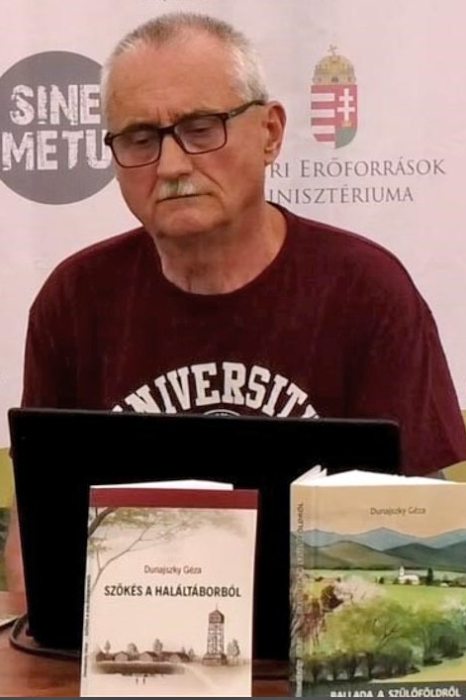

Géza Dunajszky, public writer, choirmaster, and a well-known figure of the Hungarian minority in Upper Hungary, today's Slovakia, faced traumas as a young child that are a burden to bear even as an adult. Even today, little is said about the deportation and decimation of Hungarians in Czechoslovakia and the other horrors of the Beneš era, which is why he shared his own and his family's story and began to search for the victims.

(The area that was historically the northern part of the Kingdom of Hungary, but today is mostly Slovakian territory, is called ‘Felvidék’ in Hungarian, i.e.: "Upper Hungary" or "the Highlands" – translator’s note)

Debrőd (Debrad, Slovakia), near Kassa (Kosice), was a 100 % Hungarian village until 1945. Géza Dunajszky was born here, the third son of a wealthy farmer. He was two years old when he first met his father, returning from French captivity, who knew only that he had been conceived. "The people in the village told me a lot about him, and I also knew what he looked like because I had to pray under his photo. I was sitting on top of the cherry tree eating when I heard Giza, my father's sister, and a woman in the courtyard of the local pub talking: 'Giza, your brother is home!'

"I knew it was him, and I ran to my mother yelling that Daddy was home! I even remember my mother making pancakes and bean soup," he recalls.

The father didn't talk much about his years in France. He worked for a peasant in Brittany, who was himself a minority among the French. "He urged my father not to return home, to stay in the country and make his family follow him, but he wanted to go home. He later regretted his decision. He heard that they were taking Hungarians to the Malenky robot (forced labour in the Soviet Union). When he took the train back home, he answered the question of the Russian officer on board in French, so he did not get caught."

Small hoe and sickle under the Christmas tree instead of toys

The young Géza had to grow up very fast: his parents involved him in farm work from the age of four. The family owned 45 hectares of land, including pastures and woods. "My Christmas presents were not toys, but a small hoe, a small sickle, and a small rake," he recalls. - I used to get up at 4 a.m. to feed the animals in the poultry yard, do the sweeping, help milk the cows, and remove the manure from under them. In the winter we burned lime and charcoal. After completing my tasks, I went to school. It ate me up inside, but I got it done. It helped in many situations to know how to do these things."

Hard physical work has made him more resilient and stronger. He could only study and read in the evenings, often by candlelight, which he placed in a bucket to keep the hay he rested in from catching fire. Despite all this, he looks back on his first seventeen years as a good time. "The village is in a beautiful valley with the St. John's brook running through it. An island of peace and quiet."

Killing even their memories

Géza also needed to grow strong spiritually at an early age. He was still a very young child when, at a family gathering on Christmas Eve, a relative began to talk about the massacre in Přerov. On 18 June 1945, the Czechoslovak army arrested nearly three hundred inhabitants of Dobšina and the surrounding area and took them to the Swedish Trenches near Přerov, where they were made to dig a pit and shot into it.

"They killed kids like him," an older woman, Márta, said pointing at me. That sentence was etched in my mind forever."

Another mass murder during the Beneš era had an indirect but even greater impact on his life. On the orders of the Czechoslovak president, hundreds of civilians were murdered by the Czechoslovak infantry regiment No. 17 on the outskirts of the village of Pozsonyliget (Petržalka) in peacetime in the three months following 8 May 1945. In July, ninety Hungarian young soldiers, POWs were also executed on their way home from captivity. Géza's two cousins were also killed, which he learned about months later.

"We were working in the cornfield when my aunt came to us. She turned to my mother crying. "I just wish I knew where they are buried, where I could turn under God's blue sky to say at least a prayer for them." I hugged her and told her that when I grew up, I would look for their graves." The two boys, József and István, were taken to Germany as forced conscripts in the autumn of '44, the younger not even fourteen. His parents hid him in the chimney, but he was still found.

Géza still finds it difficult to talk about the tragedy, as he had to keep his grief bottled up for a long time. For decades, it was forbidden to talk about Beneš's atrocities against Hungarians – until 1989, anyone who spoke about them was imprisoned because they were declared military secrets.

He had personally experienced the deportation and subsequent expulsion of Hungarians from Czechoslovakia from '45 onwards. It applied to anyone who declared himself Hungarian. After the World War, 750,000 Hungarians lived in Upper Hungary, but after the expulsions, this number fell to around 450,000.

In 1947, Géza's aunt, and later his dear neighbour's family, had to leave their home. As a child, all he could sense was that they would be taken away in a carriage without a farewell, under military guard.

It was years later that he learned of the humiliation his aunt had suffered at the border, stripped not only of her jewels but even her clothes.

Beaten for speaking Hungarian

He had been going to Hungarian school since '51, but he had to learn Slovak, which was made compulsory not only for children but for adults as well. "In the Slovak school, where my brothers started compulsory education, the Slovak teacher used to beat the students who spoke Hungarian," he says.

There was a lot of fighting between his parents over the language issue. His mother came from a village where people of Slovak origin lived and went to Slovak schools, so she was not averse to the Beneš politics, which his father was totally against. He once declared that he was unable to learn 'this gibberish language', which resulted in someone denouncing him for insulting Slovaks. As a punishment, he was to be sent to work in the Jáchymov uranium mine, which was the most severe punishment at the time. Only through the intervention of a friend of his wife's did he escape forced labour.

"My mother had a friend who was the head of the council. She brainwashed her in such a way that she secretly ‘reslovakized’, i.e. she declared herself Slovak. I only found out after her death when I found a document about it. She didn't want us to know about it, so she hid it among the property papers of the animals."

Géza and his classmates were reluctant to learn Slovak. "The year of our graduation, the class went on strike: we didn't prepare for class and didn't even utter a word when the Slovak teacher came into the classroom."

"This teacher, to get us expelled from the high school, smeared feces on the pictures of Slovak writers displayed in the school. But his fingerprints gave him away. He was dismissed."

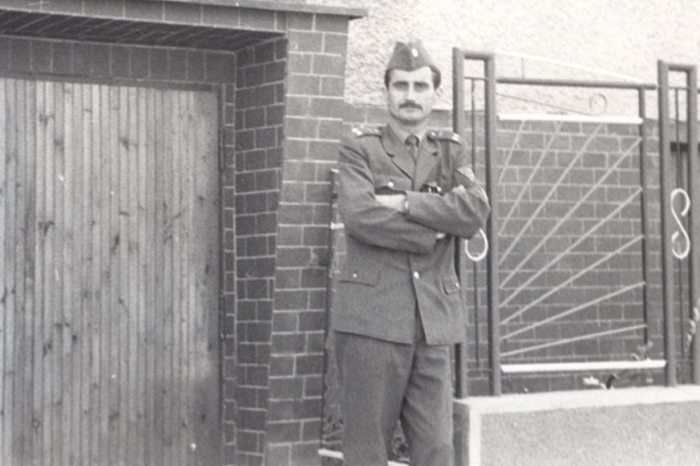

Despite all this, he passed the graduation exam in the Slovak language as well. Thus he was admitted to college and later became a teacher of mathematics and music. In order not to need his parents' support (his father had just recovered from an illness), he started working while attending college. "I vowed not to ask them for a penny. I started writing features for a couple of newspapers, which paid me a pretty good fee every month. I made more money than I did later on as a trainee teacher."

Collecting folk songs and interception

After his studies, he started teaching at the school in Felsőkirály and later became headmaster in Pográny (Pohranice). During his teaching career, he led several choirs and folklore groups, played in wind orchestras, and became a founding member, assistant conductor, and organizing secretary of the Central Choir of Hungarian Teachers in Czechoslovakia. He soon got married and had two children. Later, he got a job at the Central Committee of the Cultural Organization of Hungarian Workers in Czechoslovakia (CSEMADOK) in Pozsony (Bratislava). As head of the art department, he organized several central Csemadok events a year, such as drama, folk orchestra, pop music, and choir competitions.

Together with his colleagues and local ethnographers, they collected folk songs, material, and spiritual ethnographic material in several places in Upper Hungary. "We have managed to collect a huge spiritual treasure and have recorded several new folk songs. It took twenty years until they were all published."

Géza remembers this time as the best of his life, and not only for his professional success: it was also when he met his second wife, Éva, with whom he had a daughter.

Although he had no political role, he was kept under surveillance by the communist political police: when he joined Csemadok, he was reported by agents, probably including his own secretary at the time. "One day I had to make an urgent phone call, so I went to his office. The phone started ringing just then. When I put the receiver to my ear, I heard the voice of my folklorist colleague Imre Németh talking to politician Miklós Duray.

Later I found out that the phone also had a player that played back the recorded conversations, and I accidentally pressed that button.

Anyway, we suspected that we were being bugged because when we started talking, we heard a click and the sound quality was reduced because of the recording."

Started research later in life

In retirement, Géza began to research the fate of the Hungarians who were persecuted during the Beneš era and killed in the massacres and to search for the graves of the ninety soldiers killed in the village of Pozsonyliget. Even though almost 80 years have passed since then, except for the historian Kálmán Janics, no one has addressed the issue.

"I was sure that there were still some who had managed to escape from the death camp and were still alive. I posted a call on Facebook for people who were involved to contact me, and more and more people got in touch."

He aims to make this tragedy an integral part of the national memory of Hungary as a whole so that people learn from it and do not make the same mistake again. He later wrote three books about the period and had a memorial erected to the murdered victims. He is now working to have gravestones for the young soldiers from Debrőd and other areas of Upper Hungary in the cemetery in Pozsonyligetfalu (Petržalka).

As for what gave him the strength to endure the ordeal, he says: "You can get a blow that knocks you down, and sometimes you fall as hard as possible.

But think while you're lying there how you can get up, and if you have to, stay down for a while if that's the smarter choice.

Don't jerk around, don't try to ram anyone when you see you're outnumbered. But afterwards, stand up and do what your conscience tells you with a steady back. That's what I'm doing now."