One semi-true and one false myth about Ignác Semmelweis

Dr. Ignác Semmelweis, perhaps the world's best-known Hungarian doctor, was born into a German family in Buda in 1818 and died in a closed ward of a mental hospital at the age of 47. His life was tragic but successful in historical terms. His life and death are surrounded by myths, almost none of which are true – at least not as they are presented to mislead the public.

Myth 1 – semi-true:

Semmelweis' discovery was met with total rejection by his contemporary colleagues

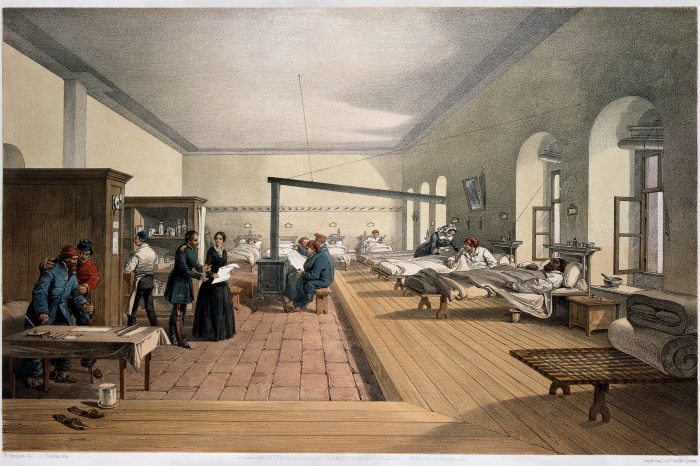

Semmelweis became world-famous gradually from the end of the 19th century, when the news of his discovery spread: he "discovered" chlorine handwashing as a means of avoiding puerperal fever, but he could only prove its effectiveness statistically, he did not yet have the necessary pathological knowledge. (The existence of microbes was proved by Louis Pasteur from 1857 on, and his discovery only gradually became known.) In 1847, after much investigation, he came to the conclusion that puerperal fever was not an epidemic, as had been previously thought, but that its cause was to be found in the clinic. A death explained the connection: a medical colleague of his died of septicaemia from a wound he had received during an autopsy, with symptoms similar to those of the women who died after childbirth. From then on, to prevent the transmission of the "corpse poison", he and his students washed their hands thoroughly in chlorinated water before each examination.

The number of deaths dropped dramatically in just a few months.

So statistics – and Semmelweis was a passionate believer in numbers, in practical effectiveness – proved the effectiveness of disinfectant handwashing. But he could not scientifically justify the cause-and-effect relationship. As a result, his colleagues were largely sceptical about the compulsory hand-washing, which was a very tedious, time-consuming procedure that also caused skin irritation. His difficult, impetuous, impatient nature didn't help either. However, documents in the archives testify that Semmelweis's teachers and friends fought tenaciously for him and his principles for many years, and stood by him even after he himself had turned his back on Vienna and went to work in Budapest. One of his English medical colleagues, who had been so impressed by his suggestion to combat puerperal fever when they met in Vienna that on his return to England, he gave several lectures on the subject, wrote to him in 1849: "The fame and truth of your discovery is now spreading in public opinion, and is understood and acknowledged in all medical societies to be a useful thing."

In 1850, Ignác Semmelweis moved back to Buda and became head of the obstetrics department of the Rókus Hospital in Pest, where he also required disinfectant hand washing. He was given an even wider scope when he was appointed professor of obstetrics at the Medical University of Pest in 1855, teaching all his obstetric and midwife students to wash their hands. His professional recognition is also demonstrated by the fact that he was invited to teach at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, but refused and stayed in Pest.

In 1860, in Vienna, he published his book Die Aetiologie... in German on the pathology and prevention of puerperal fever. Semmelweis himself sent a copy of this to the Hungarian Council of Governors intending to secure a decree for his handwashing reform – they asked the medical faculty of the University of Pest for their opinion, who supported it. Thus it became an official order in 1862 that Semmelweis's proposal should be incorporated into hospital protocol – obviously, this did not happen overnight. Semmelweis wrote open, persuasive letters to well-known professors in major European hospitals urging them to switch to disinfectant handwashing - but, of course, this had no immediate effect, disappointing him in his zeal for a good cause. After his death, his students continued to follow his practice, and disinfectant handwashing was adopted in a growing number of foreign medical institutions.

For example, József Fleischer, who was appointed head of the obstetrics department of the Rókus Hospital in 1869, surpassed even Semmelweis in rigour, so that the proportion of puerperal fever cases in his department remained below one percent.

A young doctor, who regularly sent travel reports from Europe to the Medical Weekly, wrote a few years after Semmelweis's death that "Professor Semmelweis has already made many conquests. In some places, he is followed in silence, in others he is called a leader. It gives me the greatest pleasure to write that a university as famous as that of Berlin is now proceeding on principles which at first were received with doubt."

So it is false to claim that in his lifetime no one understood the significance of his discovery – but clearly, accepting his protocol was a slow process, and in his lifetime he had not yet reached a level that would have given him, a doctor with a responsibility for all patients, the sense of satisfaction.

Myth 2 – not true:

Semmelweis was conspired against, declared insane, locked up, and practically murdered by his envious colleagues and his ill-intentioned wife.

He was 47 years old when, because of his poor mental state and his outbursts of temper, his young wife and his doctor friends turned to the renowned doctor Ferdinand von Hebra (one of Semmelweis' patrons) in Vienna for medical advice, who recommended asylum treatment. Hoping for an improvement in his condition, he was admitted to an asylum in southern Austria (not Döbling), against his will, of course. Ignác Semmelweis died in the institution on 13 August 1865. This has become the source of many rumours and conspiracy theories.

His doctor friends were considered traitors, and his wife was accused of wanting to get rid of her husband, whose human greatness she did not recognise. She was reproached for not having brought her husband's ashes back to Budapest until 1891 and for having changed his name to Szemerkényi (Ignác Semmelweis' brothers had already changed their surname to Szemerkényi long before, and their widowed sister-in-law had followed suit). Her financial and social status became much worse after her husband's death: she and her young children basically had to rely on the mercy of her relatives.)

New myths were born when he was exhumed in 1963 and his remains were examined by three Hungarian medical experts.

They concluded that Semmelweis had died of sepsis from slow-onset osteomyelitis in his right hand – the same disease he had fought all through his life to prevent.

His disturbed mental state was only thought to be a delirium accompanying sepsis.

The other theory was put forward slightly later by psychiatrist István Benedek: according to him, the insanity, which had become unbearable for his environment, could have been paralysis progressiva, which was the third period of syphilis (haemophilia) leading to death, so Semmelweis would have died soon even without the infection of his wound. (Syphilis was almost a 'national disease' at the time, and could be contracted not only through sexual transmission but also during childbirth or autopsy.) The denouement could have been hastened by sepsis from the hand wound.

The speculation surrounding his death became intense when, in the mid-1970s, György Silló-Seidl, a doctor living in the (then) GDR, managed to obtain Semmelweis's original autopsy report from Austria, which confirmed sepsis but nothing else. However, he published his book both in Hungarian and in German, in which he accused Semmelweis's Hungarian friends and colleagues of "conspiring with fellow Austrian doctors to remove him, imprisoning him unjustifiably in a mental hospital, where he was brutally murdered".

This theory, which is the most bizarre and unsupported by any evidence, has become the most popular, returning from time to time in tabloid and pulp fiction. Notable "experts" (including a popular medical geneticist, a security expert, and a literary historian) have also voted for this fictional version. "'Was he killed? Yes. By whom? How? He was isolated from the outside world, he was beaten, he suffered injuries, his wounds were infected, they were left untreated, he obtained sepsis," Silló-Seidl wrote in a 1977 article in the magazine Élet és irodalom (Life and Literature).

In contrast to him, the more sober and scientific explanation was presented by the medical historian József Antall, who stated in the same newspaper that "Semmelweis was not killed".

There is no evidence that he was treated cruelly, that his injuries may have been self-inflicted in the cell where he was locked up as a danger to himself and the public, and from which he was probably trying to escape – unfortunately, this is true of all people with severe mental illness at the time, for whom more humane methods of treatment were not yet available.

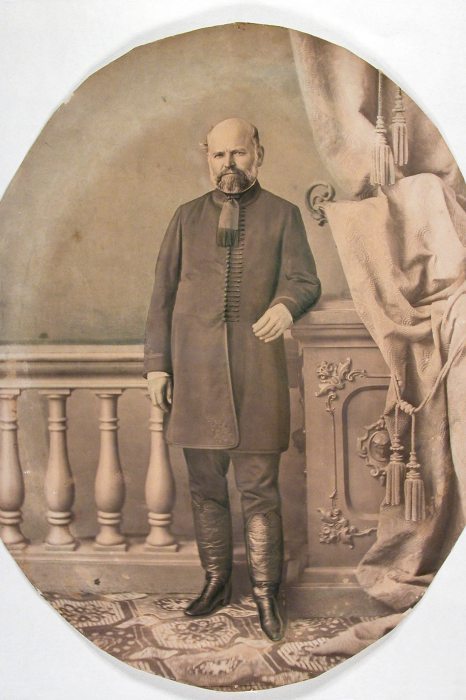

For us laymen, all we can see is that in the photo taken the year before his death, he looks almost like an old man, even though he was only 46, the father of three small children. Looking back after a century and a half, he had a tragic but successful life. "My teaching is to banish the terror of the maternity ward, to keep the wife for the husband and the mother for the child," he wrote as his creed. In fact, we owe him much more than that: thanks to his discovery, all medical interventions became safer.

Literature used:

Semmelweis Ignác emlékezetére, 150 évvel halála után. Főszerk.: Dr. Monos Emil. Semmelweis Kiadó, 2015.

(In memory of Ignác Semmelweis, 150 years after his death. Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Emil Monos. Semmelweis Publisher, 2015.)

http://real.mtak.hu/30826/1/Benedek_I._Semmelweis_MTA_2_u.pdf

https://mek.oszk.hu/05400/05427/pdf/Semmelweis_keziratai.pdf

https://leveltarimozaikok.bparchiv.hu/2023/12/08/leveltari-mozaikok-91/?fbclid=IwAR1yaV5y-IWt6J5cAGhwFz6NWLwOkenbIhiO9p0Lmtv8JW8_h8oIpZDFPwc#more-3987