Love is an awakening to yourself

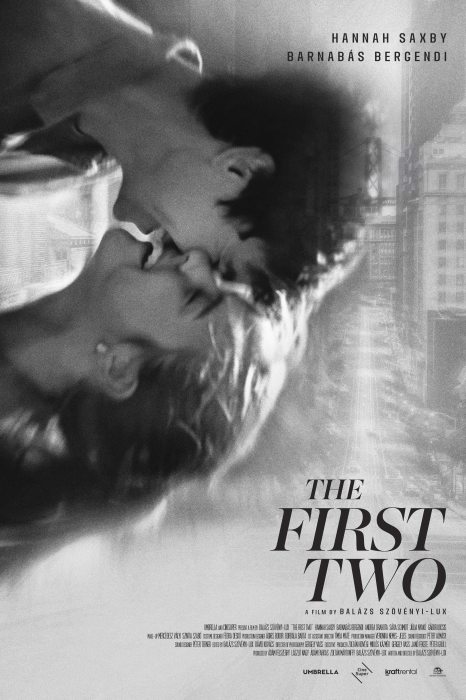

The most romantic, sensitive man I've ever spoken to, who talks about love in a way that gives you goosebumps. He is passionate, fanatic, and persistent. His first short film, Katapult, captivated audiences in Chicago, and now in April, he debuted his first feature film, The First Two – in which he plays with the idea of what if the two characters in the film had been the first two people to fall in love at the beginning of history. In this article film director Balázs Szövényi-Lux lets us closer to himself.

There are only a few loves in life like the love I had with her. I had known her for only five days, yet I felt closer to her than to anyone. I met her and love in France, as a guest of an international ecumenical monastic community. She was an American on a trip to Europe and I was the organizer. We spent six days in one place and then she went back to America. During that time we had one long afternoon together when we went to the next village. That's when it hit me: I'm 26 years old, and up until that moment I'd never experienced the feeling of being loved back. She was the first person I felt I didn't need to show myself differently, behave differently, conform, or prove myself. We were instantly on the same wavelength.

In those six days, we hugged only twice, nothing else happened between us.

Still, I knew when we went to bed at night, each to our own quarters: we were becoming more and more attached to each other. I was beginning to feel like a half-drunk.

For me, love is an intense self-awakening, an encounter with myself, in which one's innermost being can come out clearly. Love is a revelation that reaches the deepest layers of a person. It tears apart our safety nets and reveals the radiant essence of the human being while causing our deepest wounds. It is to this feeling, which is creative and destructive at the same time, that our most brutal wounds and our most beautiful experiences are linked. It is the person who is in love, or who has lost love, who writes the best and most powerful poems and songs because they experience an emotion so saturated and transcendent of the everyday. We experience a reality beyond reality when we are in love.

It was an unimaginable and suffocating feeling when she boarded the bus and disappeared around the bend to be in Los Angeles two days later. I had never wanted to go to America until that moment, but I knew then that I would because you can't just let go of that feeling. Until then, life had taught me that you can let go of everyone, you shouldn't get too attached to anyone. But I didn't let go of her, and she didn't let go of me either. We wrote letters for months. It was clear from our first letters, we both felt the same. We were in a long-distance relationship for two and a half years, then I lived in Los Angeles for three months and then she lived three months in Hungary.

From the very beginning of our relationship, the agony of a quick, forced separation, the movie Katapult was born, a double award-winner at the Chicago International Children's Film Festival. My first feature film, The First Two, depicts the last hectic days of the relationship in the capital city, tightrope-walking on the line between reality and dream.

The beginning and the end – both experiences were more for me than a person can bear.

I couldn't help but write about this feeling, keeping in mind all the time to protect her, the love we have experienced, the reality and transience of which is ours alone.

I'm a director, an old-fashioned filmmaker who makes it his vocation. I've always had something to do with film since I was a kid. And like many people who create, I believe that you can only give, you can only speak from what you have experienced and what you know. I used to be very scared to show myself, but my mentor in Scotland told me: "You'll only make good films if you stop hiding yourself. You have to go to the very edge of a cliff, but only until you don’t fall off. You have to teeter on the edge, that's what Art is about."

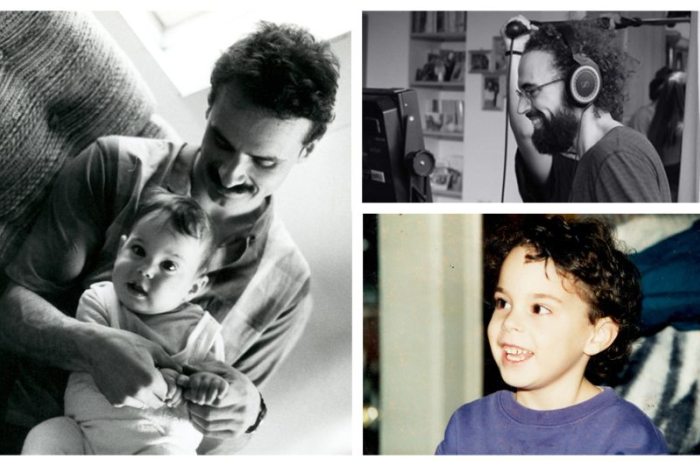

Filmmaker - I was introduced to the term when I was five, thanks to my mum. I could already see stories and characters in my head, but as I couldn't write then, I drew them and asked my mum to write in the bubbles what they said. My parents were the first to tell me about great directors, like Bergman, Fellini, or Spielberg, and my father explained to me what made a film brilliant, the timing, the tension, or the characters. It was in a conversation like that that I said I was going to be a film director. My family initially found my directorial ambitions amusing, but then they began to have concerns for me in this world. They saw that it was an unsure profession with a lot of sacrifices. They showed the Harry Potter film adaptation I had shot as a teenager with my sister to a family friend, film director András Dér and asked him what he thought of my film and the directing, and he said, "If someone loves what he is doing so much as a child, he shouldn't be talked out of it."

I understood my parents' concern. In my family, the idea was that art was a source of pleasure, essential for the soul, but having a proper job beside it is necessary. My grandparents were church-going people under communism, which was one of the reasons why they were labeled as ‘unreliable’. They started from a disadvantaged background, so they experienced always having to be twice as good as those around them, having to fight for everything - I bring that from home.

I feel I owe it to them to do whatever I do with maximum effort. Success doesn't come easy, and if it does comes easy, it's not real success.

That's why I never gave up during the shoots, because if I felt that that was it, that was the end, then I always realized I hadn't tried hard enough.

When I graduated from high school, the Institute of Film and Media of the University of Theatre and Cinematography only launched courses every three or four years, and it wasn’t one of those years so I could apply that year. Many people suggested that the Pázmány Catholic University would give me a good basis for a degree in film directing - and indeed, its intellectual environment opened me up to the world. Our film classes gave me the space to try my hand. I graduated from Pázmány University in 2013, and after that, I tried twice to get into the Institute of Film and Media, without success. For a while I worked in the editorial department of a cultural television station, I loved the environment there but felt it wasn't for me. Going out on the street and interviewing with a camera is very different from what I want to do.

I had to make a move. I looked at where in Europe there is a film training course that doesn't cost tens of millions of forints per year, that is in English, of high quality, and has a good university background, not "just" a film school. I ended up studying in Scotland, where the film directing course was part of the University of Edinburgh. When I held my diploma in my hand, I felt a void. I was tired and there was a hopeless silence inside me, I couldn't see a way forward.

I went to France to volunteer for three months. I gave myself three months to think about where to go next. At the age of 26, I was in a life crisis, even though I had always been sure that I wanted to be a film director. I had a spiritual counselor who I talked to a lot.

I thought about other vocations, even the priesthood came to my mind. But I couldn't give up love. The feeling that inspired both my films.

The magic of the ecumenical community was there in the feeling, the Love, which is the basic experience of my film The First Two. There we were like two people at the beginning of the world, not yet bound by principles, expectations, or customs.

The film plays with this idea: what if the two characters in the film had been the first two people to fall in love at the beginning of history? When living in a community, the best version of everyone appears, which is also a big trap. Because then you go home, and reality intrudes, which is not only the 10,000 kilometers of distance, but what you feel when you're lying inches away, and there's that intangible distance between you, created by different cultures, socialization, customs, and values. We had an exhilarating summer in Hungary, which was the strongest inspiration for my film, after which we felt that we couldn't go back to writing letters, that we had to have some fake, paper-based marriage to at least be on the same continent. Of course, we weren't ready for marriage, but it was the distance that we suffered the most from. Both of my films were born out of tension, one from the feeling of meeting and then parting, and the other from the tension of realizing that you have to let go of the other for the happiness of both of you. Because the distance is too great on all levels and you can't overcome it. If you are physically in the same place, you may have the time and space to work out strategies for your relationship, even if you have completely different worldviews.

But to be separated by 10,000 kilometers, 9 hours of time difference, and to think about the world in a completely different way – these two together were too much for us, it was something we couldn’t overcome.

I don’t want to start a long-distance relationship anymore. It's a trivial example, but I need to be able to sit down with the person to watch a movie, not online, at the same time, where sometimes the other person says something like this, "Let's stop it for a second, let's rewind it because I'm going out for a drink or someone's come in". It's important to me for this to be a real, shared experience. I need the other person to really be there with me.

Back then I was looking for the big fire, I found it, and I will always be grateful to have lived it, but today I don't need that big flame. Something has quieted down in me: I'm looking for peace these days. This love has shaped me the most, it has made me understand myself more, what is important to me. Now, as I stood in front of the poster of my film in the Puskin cinema, I didn't have the euphoric feeling I thought I would have. Perhaps the experience of fulfillment will come when I face the audience in the cinema auditorium.

The First Two is a black-and-white movie – there were technical and human reasons for this. The technical reason is that shooting on a micro-budget, under hectic conditions – taking into account, for example, what the weather is like, what the lights are like – you can unify the world of the film much more in black and white than in colour. In human terms, it's in black and white because my experience is that when I look back on the last day, it's a terribly plain experience. There are no colours on a day like that, it numbs your perception.

When you're standing next to the other person and you know you're going to lose them, there are no coloured memories left there. There you only remember feelings, movements, and faces. And the pain.

Agony is black and white. Because then you are not living outside, but inside. What these two young lovers are experiencing then and there is binary: yes or no? Will we be together tomorrow or not? Will you get on the plane or not? These are yes or no. It's a pure decision situation. The biggest loss of my life, the greatest experience of my life: when I was able to love. And as Sándor Weöres wrote: "It was worth being born just for that one day."

The story was written by Emese Kosztin based on the memories of Balázs Szövényi-Lux.