From a villa in Buda to a chicken coop on a farm – The life story of Zsigmond Széchenyi

„We are given imagination as compensation for what we are not, and a sense of humour as consolation for what we are.” (Count Zsigmond Széchenyi)

If István Széchenyi was rightly called the greatest Hungarian by his contemporaries, then Zsigmond Széchenyi, a later descendant of his family can be said to have been the greatest Hungarian hunter. He was a master not only of rifle shooting but also of writing, as his hunting stories and travel guides entertained and educated generations to respect and love nature, wildlife, remote landscapes, and people.

Zsigmond Széchenyi of Sárvár-Felsővidék was born in Nagyvárad in 1898 into one of the best-known aristocratic families with a long history. Among his ancestors were prominent figures of Hungarian history, high priests, and greats of the country. His great-grandfather was Count Ferenc Széchényi, who founded the Hungarian National Museum and the nation's library, and his great-grandfather, Count Lajos, was the brother of István Széchenyi, an emblematic figure of the reform era and the national awakening. Zsigmond's grandfather, Dénes, was a prominent figure in public life in the post-Reunification era, and his father, Viktor, was the chief bailiff of Fehér County. On the female side of the family, we find deeply Catholic Austrian and Czech-Moravian noblewomen, Zsigmond’s mother was Karolina Ledebur-Wicheln. The young Zsigmond grew up in Sárpentele near Fehérvár and on the extensive family estates in Austria and the Czech Republic. He was educated at the Main Real School in Székesfehérvár, then in Pest, at the main grammar school named after Ferenc József, where he graduated in 1915. For the next two years, he served as a soldier of the Monarchy, and after the defeat in the war, he began to study law in 1919. But his interests focused on languages, travel, hunting, and wildlife.

So he left law to study zoology in Munich, Stuttgart, and soon Oxford and Cambridge.

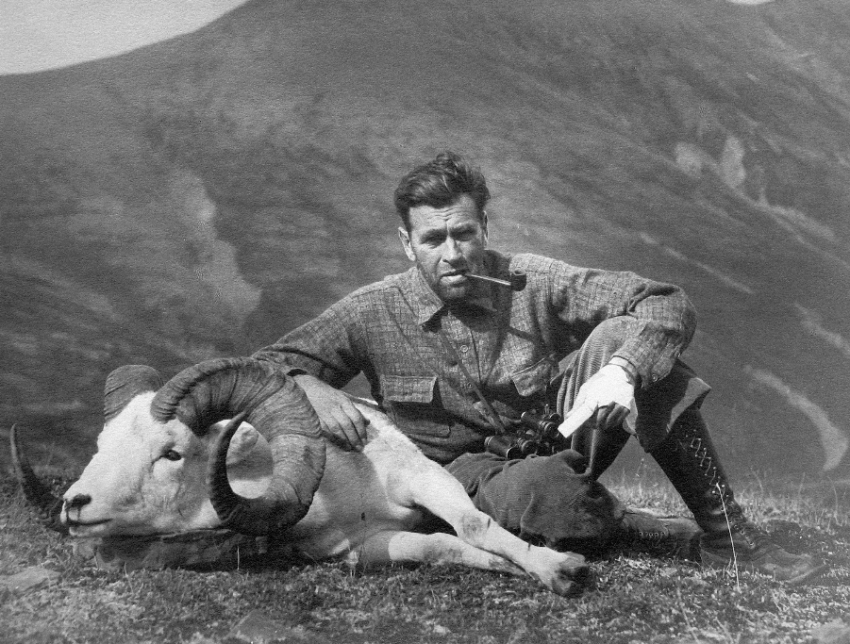

On his return home, he farmed on the estate of Köröshegy in accordance with family tradition, but at the same time, he was a passionate hunter, traveling the country and the mountains of Transylvania, Tyrol, and Northern Italy. It was then that his first small articles appeared in hunting magazines.

Wanderer of savannahs and jungles

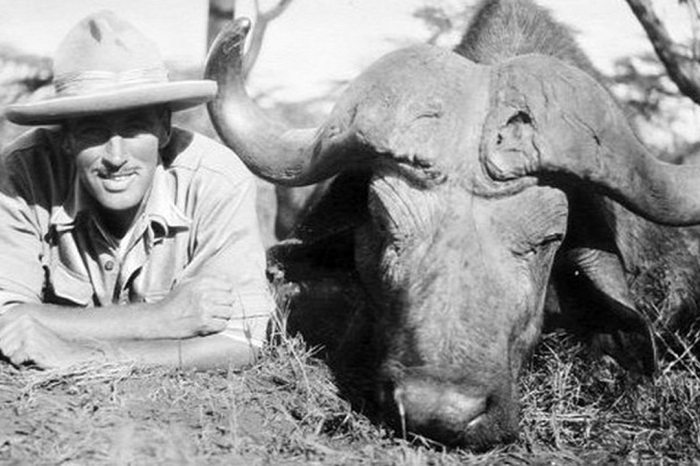

During one of his trips to England, he met Miss Stella Crowther, the daughter of a Yorkshire cotton manufacturer, whom he married in 1936. In the meantime, his hunting ambitions, supported by the income from the family estate, had drawn him to distant, exotic landscapes. For the first time, in 1927, he hunted in Africa with László Almásy, the adventurous hunter, explorer, and pilot, in the then British colony of Sudan, but in the following decade he made half a dozen more trips to East Africa, Kenya, Tanganyika, Uganda, Sudan, and Nubia.

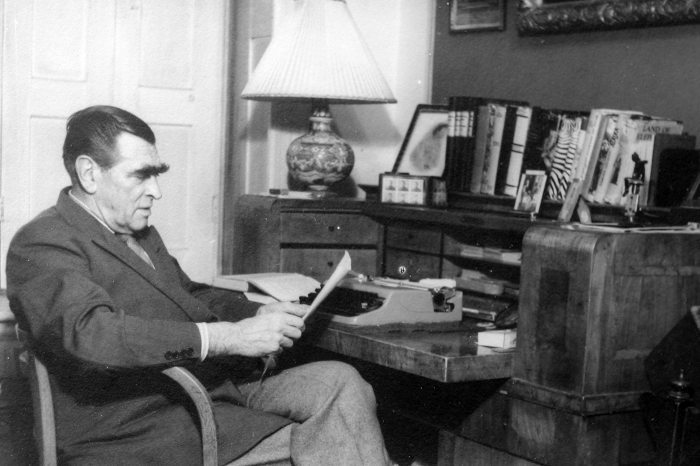

In time, the Széchenyi Villa in Buda became home to a significant trophy collection and a valuable hunting library.

During his travels, Széchenyi was not only interested in the then almost undisturbed African nature and wildlife. He also got to know the people there, their culture, their life, the beauty, and the misery of the region, which was still a colonial region.

In 1932, he wrote his first highly successful travelogue and hunting book, Csui, followed a few years later by African Campfires, which, in addition to exciting adventures, gives an insight into the world of old Africa. In 1935, he went to Alaska in America, where he hunted large bears. His book I hunted in Alaska is the story of this journey, but it is also an interesting account of the American way of life at the time. Although the great love of his life remained the black continent, he also visited India in 1937-1938. This counted as his honeymoon with his wife. He recounted their journey in his book Nahar, which again not only records the experiences of a tiger hunter, but also gives an insight into the subcontinent's artistic and cultural history, and into everyday life in the Anglo-Indies.

The Second World War was the turning point in his life. His British wife moved back to Great Britain with their son Peter at the start of the war, and they divorced in 1945. During the siege, the villa in Buda, with its unique collection of trophies, was destroyed, and miraculously only the library survived the war and the turbulent years that followed.

The world-traveling count deported into a henhouse

He was arrested by the Soviet military authorities in the days after the siege but was released after a few weeks. Then, with the confiscation of large estates leaving the family without financial support, Count Zsigmond took a job as a hunting supervisor and later worked as a specialist museologist at the Agricultural Museum. However,

in 1951, in the darkest days of the Rákosi era, he was also deported. He lived on a farm near Tiszapolgár in a chicken coop, then was assigned a forced residence with relatives in Balatongyörök, but in the following years he was subjected to constant police harassment.

After a while, he got a job in the Helikon library in Keszthely, where his task was to compile a hunting bibliography. In 1959 he remarried, married his colleague from Keszthely, a member of a noble family, Margit Hertelendy, who is still alive today, and was his companion for the rest of his life. Slowly, his fortunes have been straightened out. In 1955, his best-selling book, Chui, was republished, followed by the publication of his other works. It rated as his complete rehabilitation when in 1960 he was allowed to join the state expedition to East Africa. The material of the National Museum's natural history collection had to be replaced, which had been destroyed during the war and in the revolution of 1956. Four years later, he made one more trip to fast-changing Africa and recounted his experiences in his book Denatured Africa. He was pained but hopeful to see that the black continent was no longer the same; with all its contradictions, it was on the road to independence and modernization and the Count hoped that the price for it would not be the destruction of the wonderful flora and fauna he loved so much.

By then, his older and newer books were appearing unhindered: fourteen of his lifetime works have since sold nearly two million copies. He died in Budapest in 1967. His unparalleled hunting library of 4,000 volumes was transferred to the Natural History Museum, and his memory is preserved by a public statue, a street name, a commemorative plaque, and, above all, the memory of his readers. A biographical nature film about him was also made and released in 2019.

There is a popular anecdote that preserves the figure, character, sense of humor and even the irony of the Count, who had many adventures and hardships – while also reflects the human dignity of the majority of the oppressed Hungarian aristocracy. Following the successful return of the Hungarian expedition to Africa in 1960, state and party leaders welcomed those involved at a reception. János Kádár, himself a keen hunter, approached Széchenyi with a glass of wine in his hand, and in his familiar back-slapping style asked him the question: “Tell me, Széchenyi, how is it that you did not leave the country either in 1945 or after 1956?” The Count's reply was short but matching his character: 'You know, Zsiga would have gone, but Széchenyi wouldn't let him.'