In your professional biography, I found the word "medievalist". Why the Middle Ages? What has captivated you so much about it that you have devoted most of your life to the research of medieval literature and culture, early Hungarian literature, in particular?

I'm from Visegrád, we lived at the foot of the Royal Palace in a magical old house built on the ruins of the palace. At that time the Pilis Park Forestry Company had two flats in it for families who worked for the forestry. My father was a forest engineer, later director of the Pilis Park Forest Company - that's why we arrived there in 1950. I was one year old. The house is now part of the King Matthias Museum, our vegetable garden is part of the palace garden. As children, we had a sense of ownership of the ruins, we spent a lot of time jumping on top of the walls, we knew every nook and cranny. I was about ten when the so-called "lion fountain", reconstructed by Ernő Szakál, was inaugurated. It was a huge sensational event, you can visit the fountain even today. It was carved based on the lions and other fragments of red marble dug out of the ground, and those original pieces are preserved in the lapidarium.

When our youngest brother started school, our mother took a job as a librarian and guide at the museum next door. From then on, we came across almost every important artefact, from a sword with a thick layer of gravel from a Danube dredge to fragments of a Venetian glass cup dug out of a medieval rubbish heap. It was a special experience to see these once magnificent pieces reborn in the hands of Imre Tavas in the restoration workshop. Maybe this is how it all began.

After high school, I applied for a degree in Hungarian and Latin at ELTE, aiming for History of Art, which at the time could only be taken up from the second year. By the time I got there, I didn't want to let go of either of my majors, and that's when I became involved in the Eötvös Collegium.

The Collegium could invite non-ELTE lecturers, so my fellow Latin students invited the eminent medievalist László Mezey, with whom we spent a year analyzing one of our most important linguistic records, the Érdy Codex.

Through only this single Hungarian codex, we have been given an unimaginably rich picture of the Middle Ages! Seeing our enthusiasm, he developed a complex training plan within a few years, which aimed at educating recruits for the manuscript and print libraries of Budapest, and at exploring a new source area, for which he prepared staff. The focus was on medieval literary culture, which included everything from St Augustine to the medieval universities, codicology, palaeography, liturgy, printing history, music history, etc. His multi-faceted education covered almost everything, but he also regularly invited eminent specialists. He succeeded in finding jobs for all the students in his seminars. After university, I spent nine months in Paris and then worked for three months at the Forschungsbibliothek in Gotha.

By the time I got home, László Mezey had founded the Fragmenta Codicum research group at the Collegium – with the support of ELTE and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences – and asked me to be an assistant research fellow. I happily accepted, and eventually it became my main job for the rest of my working life. This year the grant-funded research group celebrates its 50th anniversary.

Before printing, only handwritten books, or codices, existed. What was the size and importance of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary's codex holdings?

László Mezey estimated in 1978 that the medieval Hungarian codex holdings numbered approximately 55,000, of which only a few percent have survived to the present day, most of it abroad. If the stone-built palace of Visegrád could disappear almost without a trace, how much less could the books withstand wars and fires? The destruction was not constant, of course. The Dominican and Clarissan nuns, for example, who fled to Northern Hungary to escape the Ottomans, kept their Hungarian-language codices as precious treasures, while the canons of Esztergom only took printed books with them to Nagyszombat. Thus, our medieval book culture is particularly poor in sources, and László Mezey wanted to remedy this by uncovering the codex fragments preserved on the binding plates of printed books. The damaged codices, which were no longer in use, were often used to bind printed books.

The parchment sheets of the codices were usually available free of charge to the bookbinders and were unwearable. Today, our libraries and archives have many of these fragmented books and files in their old collections, and we have begun to research and analyze them systematically.

We took great care to determine whether the carrier book was bound in the pages of a codex used in Hungary, or whether the book arrived in Hungary already bound. Our research team has analysed at least 2,000 fragments, including some outstanding pieces of international importance and many hundreds of surviving pages of a codex of domestic origin or at least of medieval Hungarian use.

Research methods have changed a lot in the last 50 years. Initially, it required a great deal of training to identify the text itself, to find the author, the work and the exact location. Today it is usually a few clicks on the internet. Fifty years ago, not many people in Europe were working on fragment research, only the early fragments were of interest in countries with a large stock of codices, and the tradition was most widespread in the Scandinavian countries, which were also poor in sources. Today, there are many excellent fragment databases all over Europe, with hundreds of thousands of fragments everywhere, registered one by one. We continue to carefully take stock of all the data that can be used to link a fragment to the book culture of the Kingdom of Hungary.

What was your first own memorable research topic?

With fragment research, you get right into the deep end; each fragment is a discovery in itself, an independent research project. We worked on some for several weeks. Fragments of the most diverse ages and genres passed through our hands, from theology to philosophy, from biographies of saints, sermons, medical and legal fragments to liturgy. The writing, musical notes and ornamentation can be used to relate fragments to age and often place. We have worked with many national and foreign colleagues from the very beginning. A short, half-page catalogue description was written of the fragments as a result of the long hours of analysis, but only a specialist can see the work that has been put in. It was important to start publishing articles on our own. I wrote my first paper on the medieval goliardic song "Ad terrorem omnium", which I found at the end of a fragment codex of a few pages.

This is a poem by a French poet of the late 12th century, full of anger against the rich, which was probably inscribed in a codex by a Franciscan monk who had travelled abroad in the 14th century. According to this, the genre was known 100 years earlier in Hungary than has been proven before.

I remember with fondness the joy of the investigation. Someone recently contacted me about the poem, and I re-read the article and was amazed at how mature it was in 1976, today I don't have so much time for a short study.

How did your major research topics follow each other, how did one attract the next?

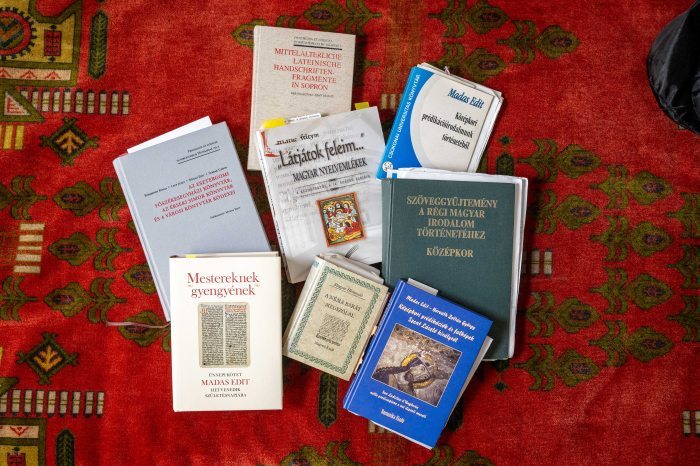

I wrote my doctoral dissertation on the Érdy Codex, a huge collection of sermons and legends in the Hungarian language from the Middle Ages, which I had studied in detail at the Mezey Seminar. This set me off in several directions: towards Hungarian language scripts, ie. written records in general, towards the literature of sermons and legends in Latin, but also towards making them scientifically popular. At the same time, however, the specific codices and the writing itself, as the carrier of the text, have always remained important, as they bear the marks of the time with great sensitivity. From a literary-historical point of view, I am primarily interested in the complex relationship between literacy and orality, and between the Hungarian-language and Latin. In the meantime, I was invited to teach in many places, and more often than not this resulted in a textbook.

In 1984, after the tragic death of László Mezey, András Vizkelety, a distinguished Germanist and codex researcher, took over the leadership of the research group. At the time, he was preparing and cataloging an exhibition of codices covering the whole of medieval Hungarian book culture, which opened in 1985 at the National Széchényi Library. He involved me in the work, which was a great opportunity to get to know the entire codex material relating to Hungary. He extended the research of the group to include codices and codex collections.

I received the other such gift package from ELTE: Andor Tarnai asked me to compile a large collection of texts from medieval Latin and Hungarian literature. It was a huge undertaking and a great personal gain for me to be able to read the entire medieval literature systematically.

László Dobszay invited me to teach liturgical Latin at the newly established Church Music Department at the Liszt Academy, which was a great experience on a human level. I wrote a liturgical Latin grammar book for the students, and even now a lot of people I don't even know come to me saying that they have learned or are learning "from me".

In 1985, Loránd Benkő launched the Old Hungarian Codices series, also at ELTE, a text edition of the language monuments with photocopies and a thorough introduction. This is a linguistic undertaking, now in its 33rd volume, but as a codicologist and literary scholar I have been able to contribute to many volumes.

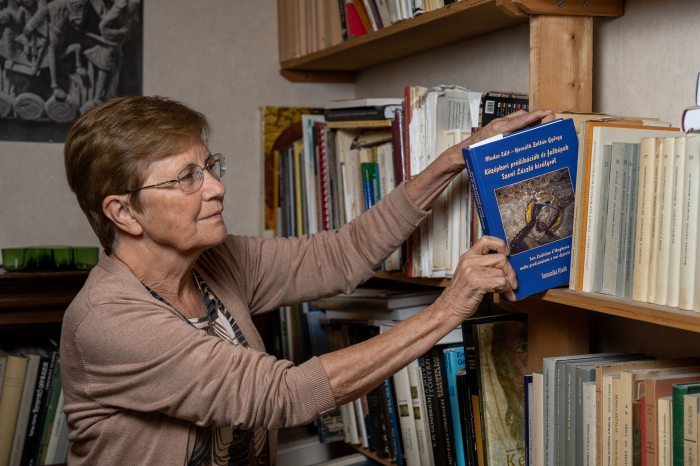

In 2000, the research group moved from the Eötvös Collegium to the Széchényi Library, the largest collection in Hungary, at the invitation of István Monok, the then Director General. The situation was ideal. Here I had the opportunity to write with him the medieval part of the book history summary “Könyvkultúra Magyarországon a kezdetektől 1800-ig"(‘Book Culture in Hungary from the Beginnings to 1800’) and became a curator of a large-scale exhibition of language memorabilia in 2009 ("Látjátok feleim…" Hungarian language memorabilia from the beginning to the early 16th century).

Your main research topic became the literature of sermons. What cultural richness have you found in the memorabilia of this genre?

This is the genre that linked the Latin-speaking high culture with the mother-tongue lay culture. From the 13th century onwards, with the birth of universities and mendicant orders, the genre was completely transformed, with sermons being preached in Latin and in the vernacular, based on carefully edited Latin speech sketches. Hundreds of thousands of sermons have been preserved in massive volumes of sermons, the originals of which were initially written in the great university centers, but within a few years, they had reached the furthest borders of Europe, including our own, through the two preaching orders. In a relatively short time, original sermons were also composed here. In my book, From the History of Our Medieval Sermon Literature, I have reviewed the Hungarian sources from St Gellért to the early 14th century. It is important to note that our early written language records appear precisely in relation to the genre of the sermon, at the meeting point of Latin and vernacular.

The oldest written texts, the “Halotti beszéd” (‘Funeral Oration’) is a short sermon itself, the Ómagyar Mária siralom (‘Old Hungarian Lament of Mary’) is a guest text in a volume of sermons, an excellent illustration for the Easter cycle, and the Gyulafehérvári Sorok (“Gyulafehérvár Lines’) are themselves short sermon outlines.

Among many other things, we have been working for about ten years on the Codex Catalogue of the Esztergom Archdiocesan Library and the Simor Archbishop Library, the Hungarian version of which was published in 2021 and the German version in 2022 as volumes VII-A and B of our Fragmenta et Codices series.

You mentioned that after university you were able to go on two study trips to Western countries, which was a great and rare opportunity at the time. Were you able to build international professional contacts later on?

Thanks to the codices I have been able to do a lot of research in large European collections, I have participated in many international conferences, I am a member of several international societies, and international scientific contacts and friendships have meant a lot to me in my career. But I can say the same about my work in my home country: I have always worked in a warm and friendly environment, both in a narrow and a wide circle, helping each other professionally and humanly. I remember my students in the same way, and I am still in touch with the old ones.

The wider public got to know your name this year when you received the prestigious Széchenyi Prize. But you have always been a leading figure in the academic world and have received several awards.

I have received several high professional awards, but perhaps most of all I was delighted to receive a book of studies entitled "To the Best of Masters", which my colleagues put together for my 70th birthday. Unlike most of the commemorative volumes, this book is not a "mixed bag", but contains very high-quality medieval source studies from 50 of my colleagues, former students, and friends. Each study directly touches on what I have ever dealt with, and what I have discovered here is how, despite its diversity, it all points in the same direction.

Hagiography – a word that has been a dominant feature of your professional career, but is mostly unknown to ordinary people. Hagiographical literature is a collection of writings on the lives and legends of the saints. Why is it important to research and explore them?

An average person today celebrates the feast days of the saints as name days, but they are ecclesiastical holidays that cover the entire ecclesiastical year, from St Andrew to St Catherine. The saints are role models, teachers and helpers to the praying person.

In the Middle Ages, the days of the year were named after feasts (St Andrew's Day, the Day of the Blessed Virgin Mary), churches were the property of the patron saint and bore their name; half of the liturgical and sermon books, and all the legendaries, were about saints. Murals and panel paintings in the form of statues were everywhere. Anyone who studies the Middle Ages lives in close proximity to the saints.

In the Middle Ages, the most popular collection of saints' biographies was Jacobus de Voragine's Legenda aurea, or Golden Legend. It was also the most important source of medieval Hungarian legends. I missed that it wasn't available in Hungarian today, so in 1990, Balázs Déri and several of my dear colleagues and students and I made a rich selection of it. An equally important and gratifying work - though primarily the merit of Gábor Klaniczay – was the second volume of Legends and Miracles: Saints From the Middle Ages in Hungary, published in 2001. In addition to the legends and miracles of well-known saints previously unavailable in Hungarian, it contains the legends of several lesser-known saints (e.g. Salome, Kinga, St. Elizabeth the Younger of the Árpád House).

One of my favourite projects was researching, transcribing and translating medieval sermons on King Saint László. It was through the sermons that the legends of the saints reached illiterate people. I managed to collect 22 sermons on King László from the 13th century to the early 16th century. The collection shows how both the genre of the sermon and the cult of Saint László evolved over the centuries. Zoltán György Horváth illustrated the volume, published in 2008, with his own photographs and details of some 250 frescoes of Saint László.

Just recently, you gave a radio lecture on the Old Hungarian Lament of Mary. How can you bring the old language memories closer to ordinary people in a simple and understandable way?

The most famous written language memorials, the Establishing charter of the abbey of Tihany, the Funeral Oration, or the Old Hungarian Lament of Mary, still have a great appeal. People learn about them at school, have heard about them, and are eager to see them in the original. That's why exhibitions are important, where people are amazed at how tiny the Leuven Codex is, how it fits in the palm of a preaching monk's hand, and how huge the Tihany Charter is, sewn in the middle, on which you can actually make out the Hungarian words. Suddenly they become real, they evoke the era, and they arouse interest in other old written scripts. It is important to have transcripts that can be understood by the lay reader, facsimiles that can be browsed by anyone, and lectures that are linked to specific occasions and aim at making old written texts more popular.

On the website of the National Széchényi Library, you can find digital copies and editions of many Early Hungarian written texts, with plenty of literature. But perhaps the first step should be taken by good Hungarian teachers.

As a farewell, I would like to draw the attention of the readers of kepmas.hu to the fact that on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the foundation of our research group, a comprehensive exhibition will open in 2025 at the National Széchényi Library entitled From Codex to Fragment, from Fragment to Codex: Book Culture in Medieval Hungary. In addition to the most important Latin and Hungarian-language codices, codex fragments will also be on display, illustrating how fragment research has contributed to a better understanding of our book culture. Since my retirement, the research group has been led by my colleague Gábor Sarbak, I have worked with him and Judith Lauf from the very beginning, and the future is in the hands of our younger colleagues.