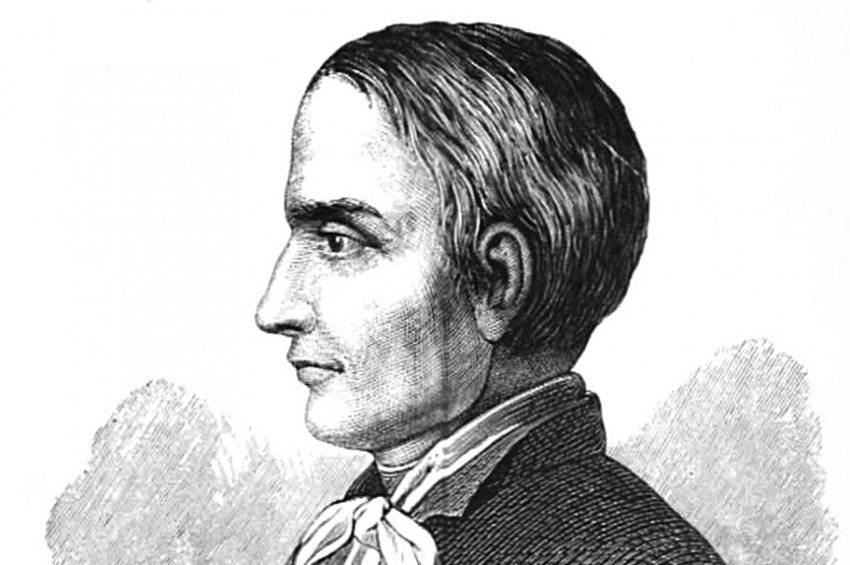

Speaker of 30 languages – Sándor Kőrösi Csoma, life of the wayfaring scientist

Sándor Kőrösi Csoma, the gifted scientific traveller, wrote his name not only into the history of Hungarians through his perseverance and sacrifice.

Departure from a corner of Transylvania

Sándor Csoma was born into a family of Calvinist Szekler-Hungarian border guards in 1784, in the village of Kőrös not far from Covasna (Kovászna), in the southeast corner of Transylvania. From 1799 he studied at the Reformed College in Aiud (Nagyenyed) – even then his extraordinary linguistic talents were apparent – completing his college studies in spring 1815. Between 1816-1818, he entered into Oriental studies, Oriental languages, Hebrew, Arabic, Persian and Turkish at the University of Göttingen with a modest scholarship from Aiud. This is also where he acquired the foundations of English and French. By the time he returned home, he wrote, read and spoke 13 living and extinct languages.

He decided to dedicate his life to the research of his Hungarian ancient homeland, which he suspected lay in far-off Asia, and the peoples and languages related to the Hungarians.

At that time, the concept of Hun-Hungarian, indeed Uyghur-Hungarian kinship was alive in both Hungarian and European science, which encouraged him to seek the cradle and kin of Hungarians in the former territories of these peoples.

Half way around the world

In possession of a modest amount of cash, in November 1819 he set off eastwards, never to return. It took two years, having been delayed by wars, natural and human factors, and after transiting through Alexandria, Aleppo, Mosul, Bagdad and Teheran, before he finally reached Kabul in Afghanistan. In the meantime, in Teheran, he left his books, papers and European clothing with the British ambassador, reckoning that he could progress in greater safety and with better results when dressed in Armenian attire. On his travels he learnt about local cultures, peoples and languages. His route took him via Peshawar, Amritsar and Srinagar towards the British Raj of India. He made it to the western arm of the Himalayas and the province of Ladakh in northern India, but it seemed so difficult and hopeless to travel on from here that he preferred to turn back. This is when he met William Moorcroft of the East India Company, on whose behalf and working in the service of the British, he began to study the language, culture and religion of Tibetans living between the Karakorum and the Himalayas. Adapting himself to the local conditions, he resided in Zanskar and Phugtal Buddhist monasteries and Zangla royal fortress amidst most spartan conditions. Aided by his colleague Lama Sandje Puncog, he acquired the Tibetan language and studied the holy scriptures of Tibetan Buddhism. Over the next few years he compiled a Tibetan-English dictionary and a volume on Tibetan grammar, which were published in 1834.

He ate little, his main food being tea mixed with yak butter.

He dressed simply, he lived in unheated cells or huts, but he remained steadfastly enthusiastic about his exhausting and eye-straining work as he studied ancient manuscripts.

In the meantime, he lived in the hope that sooner or later he would be able to continue his journey on the northern side of the Himalayas, towards the secretive Tibet and Central Asia which he suspected was the ancient homeland of the Hungarians. By this time his publications had made him a recognized researcher in scholarly circles and in 1834 he was elected a member of the British Asian Society. A few of his works made it back to Hungary and he conducted correspondence with Hungarians as well. In 1833, he was made a corresponding member of the Academy, the Hungarian Scientific Society.

From Calcutta to the foot of the final mountain

The fact that from 1832 the Asian Society gave him a modestly paid job in its library in Calcutta wrought a favourable change in his working conditions. His chief task was reviewing the scientific collection including the Tibetan manuscripts. He published a series of scholarly papers, including an essay on the life and teachings of the Buddha and studies on Tibetan linguistics. In the meantime, he spent a few years in the Himalayas, on the border of Bhutan, Sikkim and Nepal, studying the local languages; by this time the number of languages he had acquired certain degrees of proficiency in ran to around thirty.

His grand plan was to cross through the mountains and make it to Lhasa, the Forbidden City, the hub of Tibetan Buddhism that was closed off to Europeans, where he intended to search in its famous library for sources referencing the Hungarians.

After lengthy preparations, in early 1842, aged 58, he set off on this great journey. However, he fell sick with malaria on the border between India and Nepal. Thus he was forced to halt in the city of Darjeeling, at the foot of Kangchenjunga, the third highest peak in the Himalayas, in order to recuperate. However, he was so weakened by fever that he passed away on 11 April 1842. He was buried in the British cemetery in Darjeeling and the Asian Society erected a fine memorial over the grave. In 2008, his cell in the Zangla royal fortress was declared a memorial site and the building was restored with private and state funding from Hungary.

Tivadar Duka, the Hungarian doctor living in India and then London, became his first biographer. He collected his manuscripts and bequest and, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Kőrösi Csoma, translated the majority of his works. The volume Life and Works of Alexander Csoma de Kőrös was published in English and Hungarian in 1885. This work also played a large part in the fact that he is regarded by international Oriental studies as one of the greatest scholars of Tibetan philology. Here in Hungary, József Eötvös gave a memorial speech on him at the Academy in 1843, his papers were published and later on a scientific society and institute took on his name. As a mark of respect, the village of his birth changed its name from Kőrös to Csomakőrös. Buddhists also cherish his memory, several stupas have been raised in his honour, in Japan he is revered as a bodhisattva even though there is no evidence that he converted to Buddhism.

The most fitting tribute to his life is the epitaph formulated by István Széchenyi:

“Without money or applause, inspired by resolute, persistent patriotism, a poor Hungarian - Sándor Kőrösi Csoma - sought the cradle of the Hungarians and finally succumbed due to his endeavours. He lies in eternal sleep far from his homeland, but he lives in the souls of all good Hungarians.”