Hungarian doctor saves speleologist in Turkey – Intensive care unit at a depth of a thousand meters

In the last few weeks, the world's attention has been focused on the Morca Cave in Turkey, where American caver Mark Dickey fell sick more than a thousand meters deep. Dr. Zsófia Zádor, an anaesthesiologist, headed to work at the hospital in Balassagyarmat on the morning of 3 September, and less than 24 hours later she was at the cave entrance ready to help her fellow caver in crisis. How can you run an intensive care unit at a depth of 1040 meters? Here is how she recalled the events. A chronicle of a heroic life-saving and rescue operation.

From on-call to the Morca cave

Dr Zsófia Zádor, an anaesthesiologist and intensive care specialist, was on her way to her workplace, the Kenessey Albert Hospital in Balassagyarmat, on the morning of 3 September when her phone rang.

Within hours, it became clear that she had to leave for a faraway destination: Turkey.

The Morca cave in the Taurus Mountains in southern Turkey had been the site of a caving expedition for days, but one of the team, American Mark Dickey, fell ill on 1 September while deep in the cave, suffering from abdominal pain and vomiting blood. On 2 September, his fiancée Jessica, who was also part of the team, contacted Dr. Dénes Ákos Nagy, the medical officer of the Hungarian Cave Rescue Service (BMSZ), and asked him for advice on what medication she could give Mark to help him at the depth of 1,000 meters. From there, events accelerated, as by 3 September the man's condition had deteriorated and it became clear that rescue would be needed.

At 1276 meters deep, Morca Cave is the third deepest cave in Turkey. Discovered in 1996, the international cave exploration community has increased the number of known passages year after year with regular exploration expeditions. The 2023 expedition, of which Mark and Jessica were both members, aimed to explore the deepest part of the cave and to map new passages that have been discovered in recent years. They also wanted to collect samples of bacteria and fungi of unknown origin covering the wall surfaces.

The rescue, we now know, was a success – the Hungarian team members arrived home on the night of 14 September, and after a few hours' sleep, they gave a detailed account of what happened and how.

"We are very good friends"

The Hungarian Cave Rescue Service was founded in 1961 and became an association thirty years later. They provide assistance to people in difficult situations in caves or other hard-to-reach places. Since their start, they have had hundreds of alerts, helping around 500 people, mainly within the borders, but this was not the first time they had been called abroad.

In this case, the Hungarians were the quickest to react in Europe: the situation of the Hungarian Cave Rescue Service is unique among similar European organizations because they have two doctors on their team who are able to go down to such depths and work there.

One of them is Dr. Zsófia Zádor.

"I've been hiking since I was a child, which must have had something to do with my fascination with this world," she begins when I ask her how a doctor becomes a caver. She says she started caving during her university years. On the afternoon of 3 September, four of them – Zsófia Zádor and three cave rescuers – boarded a plane from Budapest, arrived at the cave at dawn the next day, and after 13 hours of strenuous climbing, they made their way down to the patient.

Zsófia Zádor didn't know what to expect beforehand, as communication with the people deep down the cave was difficult. "I had a scenario in my head that the patient would no longer be waiting for me. I tried to ignore that one. The other was that we might meet halfway down on the rope," she says. In the end, a third, lucky scenario came true. Mark's paramedic fiancée, after coming out of the cave to ask for help, went back down to join Mark and his team in the deep. She was able to replenish fluids by intravenous infusion and was able to give antacids and medication to him, thus preventing his circulation from collapsing.

And what was the moment of meeting them like?

"Everyone was smiling, I remember that much. But Mark was very pale, which indicated that he had lost a lot of blood," Dr. Zádor recalls.

- We are very good friends," says the doctor, as the members of the Hungarian Cave Rescue Service have known the American caver for a long time.

"An exchange program between Hungarian and American caving instructors started eight years ago. Mark was the first instructor to come to Hungary from the US and then became actively involved in the Hungarian caving scene. So when he got sick, Jessica contacted me straight away," explains Medical Director Dénes Ákos Nagy.

Intensive Care Unit at a depth of a thousand meters

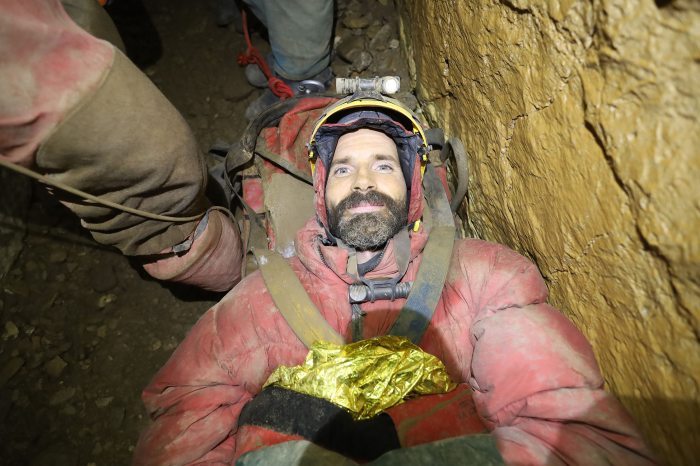

The forced ICU was set up in a bivouac at a depth of 1,040 meters. (Bivouacs are small areas away from the water, having as much horizontal surface as possible, suitable for only a few people to sleep in down in the cave).

"It was interesting to create this small intensive care unit at a depth of a thousand meters. Different medical equipment kept coming down to me. I was constantly watching for side effects and kept trying to avoid complications," she explains.

In the meantime, blood products had to be obtained from the Turkish authorities, which were constantly being brought down by small teams.

"By the time the doctor got down, the patient had been bleeding for 30 hours. We knew that a gastroscopy was not possible. There was also no way to stop the bleeding, so we had to use continuous intensive therapy, which could treat the consequences of the bleeding."

"It was like filling a leaky pot for six days until the patient could come to the surface," the medical director sums up.

"The danger of gastrointestinal bleeding is that it can worsen or improve relatively quickly at any time. When I was down there, he had such an exacerbation. After the first blood transfusion Mark was fine, he felt he could come out on his own. I suggested that he should be brought out on a stretcher because I expected his condition to deteriorate. 6-7 hours before I left, he almost had another circulatory collapse, which was eventually prevented," says Zsófia Zádor. – When I felt he was better, I took a nap for two or three hours, but I told the others to wake me up if anything happened." During her days in the cave, the doctor also had her low points: she struggled with shoulder pain, and it was alarming for her when Mark's condition worsened.

"If we don't get there on time, he probably won't survive" – she says when I ask her what she thinks the chances would have been for the sick caver without medical help. Finally, he was brought up on a stretcher, by which time Zsófia Zádor was already on the surface, having been replaced by Italian, Bulgarian, and Croatian doctors. Finally, on Monday 11 September, a few minutes before midnight, Mark Dickey was brought to the surface. The exact diagnosis was not known in the cave, but it was suspected to be a stomach ulcer. This was confirmed: Mark was taken by helicopter to the hospital after the rescue, where he was seen in a state of severe haemorrhage. He was given more blood and a gastroscopy was performed. He has now been discharged from intensive care.

Two hundred people took part in the rescue

The first four-member Hungarian team's flight ticket was bought by the president of the association, Dr. Miklós Nyerges. After that, two more Hungarian missions were able to travel with the help of the Counter Terrorism Centre (TEK), the Ministry of Defence, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The purpose of the mission was to take additional medical equipment to the site, and to keep the first team alive with food and warm clothing.

29 Hungarian cave rescuers took part in the rescue: in addition to the Hungarian Cave Rescue Service, the Bakony Cave Rescue Service and Hungarian cave explorers from Transylvania also helped.

At an international level, a total of 200 people took part in the operation. The situation was made easier by the fact that the Hungarian Cave Rescue Service is a voluntary organization, so they did not have to wait for the bureaucratic channels and an official invitation letter from the Turkish authorities – unlike the state-run services of other nations. "If we had to wait for that, Mark would not have survived," says Ákos Nagy.

The deepest cave in Hungary is 300 meters deep, compared to the Morca cave, which is situated at a depth of more than 1,000 meters. Right at the entrance, you are greeted by a ten-meter drop, so you have to use a full-body harness straight away. The cave system is divided by vertical shafts with horizontal passages in between. "You have to climb up the ropeways by your own human strength, there are no other mechanized solutions. Even the patient in the stretcher had to be carried up by hand," explains András Hegedűs, the Hungarian Cave Rescue Service’s head of operations.

The average temperature is 3-4 degrees Celsius all year round, with a humidity of 100 percent. Working in these conditions, and the lack of communication was also a problem, as between 1040 meters and 500 meters, there were no means of contact or only with the help of couriers. The fact that, after Dr Zádor went down to the patient, those on the surface did not receive any meaningful information about what was happening down there for two days is a good illustration of this problem.

The rescue operation in numbers

During the rescue operation, 1,500 meters of rope and 400 other devices (carabiners, belaying points) were used. Sometimes there were close to a hundred passages on a single section of rope in a single day, so if something broke, it had to be replaced. A special ropeway was built to bring the patient to the surface on a stretcher: 2,500 meters of rope and 1,000 pieces of equipment were needed. 36 hours was the longest someone could stay down there without sleeping. Fifty descents were made by the Hungarian team, and more than 2,000 working hours were invested in the rescue.

The rescue service has five to seven emergency calls a year, and such an organization can only be sustained by professional caving volunteers who go to caves and practice in their free time because it is their hobby, their passion.

Their operations are funded by the 1% of tax offerings, but recently they have also received specific donations.

(In Hungary, you can request that 1% of your previous year's paid personal income taxes be given to support a non-profit organization – translator’s note)

They hope that they will be supported even when there is no such large-scale action. Simply so that they can exist and be available when they are needed.