It is a deep, dark night. My forty-second night in the African jungle. I lie on my back in a double sleeping bag in the tent. My hands on my chest, my eyes closed, only occasionally opening at a strange sound that pierces sharply into the night. Automatically, awakened, as if seeing it would remove the power of the unknown. But I see nothing but the tip of the tent pointing skyward. Many times I have been afraid, with the paralyzing power of fear, yet I have set out, even longed to be on this journey.

That night, as if I had lost my mind, I woke up and walked out of the camp as I was, into the engulfing darkness of the African jungle. I didn't want to be afraid anymore.

I didn't know then that fear protects, warns, and signals. It's like a guardian, swinging around and stopping you just before the abyss.

For a long time, I believed that fear was just a barrier and a pullback, that it was the reason I didn't dare, and I wanted to get rid of it. That night I could have died of my own free will. Not seeing what I was stepping on, what was coming towards me, what I was bumping into, where I was falling, or what would devour me. I think that's what Kundera would call "the unbearable lightness of being". And indeed, when you are on the verge of cessation, suddenly everything becomes simpler, slower, almost still, and beautiful. You become that too, for yourself. It was that very night that I learned that my fear is me. I was afraid of myself, for myself. Because what happens when I’ll no longer be here?

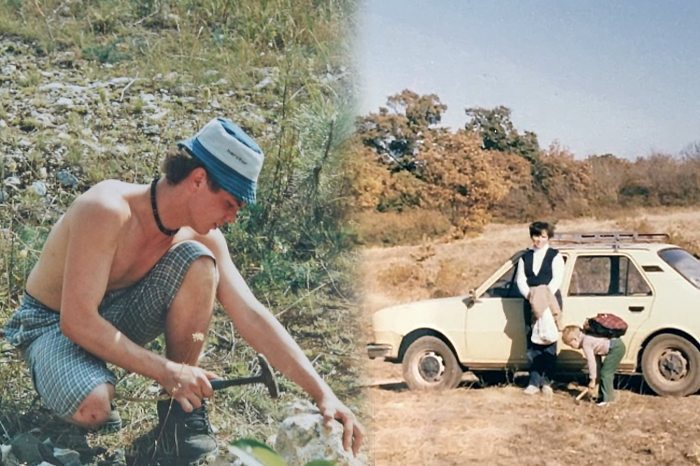

For years I wrote a diary because I was lonely. I went on many expeditions as a lone Hungarian, surrounded by people of many different nationalities, with whom I had no opportunity to talk deeply, understand or even share the spiritual processes, changes, and doubts that were going on inside me. The jungle is unpredictable and in this unpredictability, you can only count on yourself, on your own presence of mind.

On 3 January 2011, I said goodbye to my parents at Ferihegy airport in Budapest, and the flight to Paris took me with my meagre luggage to the French capital, where I was greeted by windy, cold weather. As I was heading for the tropics, I had brought no warm clothes other than a sweater I was wearing. The next morning, I took a shuttle to Orly airport, where after a short layover, I left for French Guiana. As we slowly reached the coast of the continent towards the end of the 10-hour flight, the canopies of huge, straight-edged trees peeking out of the tropical rainforest could be seen through the tiny windows, almost fighting for the scorching sunlight. I thought we were about to land in the middle of the jungle when the giant plane turned sluggishly and we glided down onto the concrete tarmac of Cayenne's airport. Soon after I had collected myself and my luggage, I stepped out into the lounge, where André appeared, who, by some fifth sense, found me in the crowd and greeted me. Later he told me that I was the only one who looked like a geologist.

As we stepped out of the airport, I was hit by the hot, balmy, humid air of the tropics. It was almost suffocating, yet I fell in love with it instantly.

Even the journey to the hostel was an indescribable experience. Everywhere you looked, there was vibrant greenery, exotic plants and birds bursting with life, and dazzling four-petalled and tiny jagged flowers. I took a short stroll around my bungalow and nearly ran over a good forty-centimeters lizard with a tail that was a garish shade of blue-green. Vultures were circling over the hills covered in lush vegetation. And the sounds! I’m going to record it once. I was expecting something similar, but not this variety. Buzzing, hissing, crackling all around, with a wide variety of rhythms, volumes, and timbres. Like the voice of angels, as if coming from the sky, enveloping and filling everything.

I've never been interested in tourist destinations, famous capitals, or popular sights, I always preferred unspoiled landscapes. I had a desire that followed me throughout my childhood: I wanted to go somewhere no one had ever been before. As a boy, I loved the books by Gábor Molnár, Zsigmond Széchenyi, and Gerard Durrell, who were the real adventurers in my eyes. They were the first to 'tell' me about endless savannahs, lions and elephants, musk oxen, and unforgettable hunting adventures. I always had a longing to tread the paths that my favorite hunter-writers had cut a hundred years ago in the African jungle.

I grew up in Kápolnásnyék, in a village on the shores of Lake Velencei, in a friendly house surrounded by solemn trees and a huge garden, where I was always greeted at the gate by my mother's embrace. I was loved. I am still loved, in a way I don't think I deserve. They watched over us and cared for us. Now it’s myself, my sister, and the grandchildren that mean everything to them.

I don't have many memories from my childhood, just a feeling that there is a place where it's good to be, where it's good to come home to.

I see my parents as good, more than good. They both have different attachments to us. While my mum is more of a cuddly type, my dad is less emotional, but I can count on him in every situation, he is my safe background. They've done everything they can to make life good for us. Maybe too much. They took care of everything for us, which is why later, when I was in a situation that was unknown to me, or when I had to do something on my own, I always doubted myself, I was unsure if I was able to cope.

If we weren't with our parents, we were with our grandparents, especially during the time when our parents started building a house. The four grandparents also loved spending time together, they often got together. I saw in our family a sense of togetherness, of belonging together, the words of Dumas' famous novel were true for us: 'One for all, and all for one'. I know that sounds too good, but I consider myself really lucky to have been born into this family. But it is very difficult to live up to such an image of warmth and intimacy. I would say the bar is set high. I could never do as well as they did. But I try all the same. (smiles)

When I was ten, my mum and dad bought the neighboring property, which had a thatched-roof farmhouse and at the end of the garden a once-used blacksmith's shop with wooden doors, full of scrap iron and lifeless tools. Instead of tearing it all down, my father turned it into a museum. He turned the farmhouse into a museum-country house, where he collected objects of local history. This was the beginning of something that defined me. At the age of eleven, I started working here as a guide in the museum, which is still in operation today, and where, at my grandfather's initiative, we also exhibited a collection of minerals. He was the first in the family to get involved in mineral collecting. He was a short, stocky miner with tiny blue eyes, full of love. He was receptive to the beauty of minerals, and his work gave him access to a variety of stones. He had a passion for collecting and that seems to be in my genes, too. Whenever we were at their place, I would stop in front of Grandpa's cabinet and look at the stones, one by one, in their various shapes, but I would just look at them, not touch them. I watched his collection grow week by week. I had a close bond with my grandfather. He was the first one to give me a hammer and dared to take it under the ground or into the mountains. He took me to explore places that took my breath away.

Sometimes I wonder if he sees if he knows, what a mark he has left on me. That by taking my hand, which at that time was so small it was lost in his palm, with his big, charcoal-stained hands, he gave me passion and purpose. A purpose, to be the best mineral photographer possible?

That it is because of him that I see what is beautiful, what is good, what treasures are hidden in the depths, if you work hard for them if you are not afraid to get your hands dirty if you dare to get down on your knees?

At a very early age, at thirteen I left home to study at the boarding school in Pannonhalma. For the entrance exam into the six-year high school, I arrived with my father. After the exam, we walked around to have a look at the abbey. Our guide was a senior student. At the end of the tour, I casually asked him what I should know about the high school if I was accepted, and what I should expect. "Well, there are classes here on Saturdays." Huhh, I thought, that's not so good. Then he continued, "You can only go home once a month, but sometimes even less often." Well, I say, this is getting worse. But the real shock came when he told me that "only boys study here"! Now that's a complete disaster. It took me years to come to terms with the situation. The first year was torture. I literally felt like a bird that has flown the nest but cannot yet fly. I was cold. Many evenings I wandered alone within the ancient walls of the abbey, surrounded by centuries-old paintings of the ancient abbots, archbishops, and other high religious officials, with their grim portraits looking back at me. They gave me the creeps. I was genuinely afraid of some of them. Their eyes were digging into me, almost looking into my soul, and I didn't want them to. I wanted understanding, not judgment.

When I graduated from high school, there was a national competition whereby the student with the best entry was automatically admitted to the ELTE Geology Department. I entered the competition and won. My parents disagreed because they wanted me to become a doctor, but I knew I was not the type. I became a geologist. At the same time as I graduated from college, I was involved in a research project in Northern Hungary, and as a result, I became fascinated by exploration geology and fieldwork. I first started working abroad in Turkey. I became an ore geologist, exploring gold. I'm looking for rocks from which certain metals can be extracted. There are companies that drill these rocks, take samples, and we geologists look at them, analyze their ore content, make 3D models of them and then calculate a stock. Anyone who has seen rocks that are two billion years old will probably know what it feels like to hold them in your hands.

We are holding in our hands a time so long ago that we cannot even imagine its temporal dimension.

I am attracted to minerals because of their beauty. It sounds so simple, but it's almost an obsession, an addiction, an admiration. Some see them as art, like a painting, some as an investment, like real estate, and others believe in their healing powers. The pieces I like best are those I have collected myself. One of my favorite pieces is a garnet crystal I found in the Börzsöny, in the woods near Verőce.

Minerals - Photo: László Kupi

Later on, we were asked by the Rwandan government to assess the country's raw material reserves. One of the projects on this expedition was sapphire exploration. My wife's wedding ring has one of these sapphire crystals cut into it, which I dug up there in Rwanda. I specialized in ore exploration because I felt that ores were somehow tangible, as opposed to, for example, oil. It's like mathematics for me. I was never any good at algebra because I couldn't grasp x2, but I really liked spatial geometry, which always got me out of trouble. If I can see something in three dimensions, I can understand the connections within.

I was thirty-four when my childhood dream seemed to come true because the company I worked for sent us to the desert in Africa to prospect for gold. I woke up there every morning feeling blessed to have been given this opportunity. We lived in simple tents and slept on small camp beds. There was nothing else in the tent except the bed, a small metal cupboard, a tiny desk, and a lamp that ran on a generator. The generator was switched off at 8 PM, and immediately our camp was plunged into darkness. Many summers I would pull out my bed in front of the tent, lie on my back and just look at the stars. The sky was clear, with an almost unimaginable number of stars shining in the sky for an eye used to the skies of big cities, and the constellations were clearly visible because there was no light pollution nearby. We lived among Bedouins who taught us all the tricks of making their famous spicy coffee. I was in awe of their incredible sense of direction as they unerringly found their way home in what seemed to me to be an endless and desolate desert.

It was in the African desert that I lived through the biggest storm of my life, and it was there I felt the coldest in my life, it was so cold then that even the pyramids were snowed in.

Although I was impressed by the unrelenting wildness of the rocky desert, I felt that it was not yet the real Africa. I wanted to see the face of the continent, the animals and people that Kittenberger had written about. And then it happened. I received an email from one of the world's most serious consultancies, whose research was taking place in the rainforest of Gabon: "We would love to welcome you to join our team as a geologist."

One time we were on an expedition in the Congo, where we had local guides walking barefoot in the wilderness. One of them stuck his toe into the elephant droppings littering the road and found that it was still warm, so the animals were close to us. We went after the elephants, I always had a camera with me, and I was determined to take pictures of them. Of course, our guides warned us to be careful with these animals, because although forest elephants are smaller than their savannah counterparts, they can be more aggressive. Especially when they are protecting their territory or their young. Heart pounding, we crawled closer and closer to the herd, finally, we were about ten meters away when they spotted us. Suddenly, fear surged through my veins, and for a moment I stood stunned at the sight. It was unbelievable, the way the ground shook with the thumping of the elephants, their trumpeting deafening, in a way that I could feel the vibrations in my stomach. Suddenly the elephants started to move, at first, we didn't know if they were running away from us or towards us, but then it turned out that most of the herd had run away, it was a male elephant that was coming towards us. Thanks to adrenaline, we were running faster and faster and managed to take cover. Then we saw that there was a smaller elephant footprint next to the big one, so we should have known that they were going to protect the little one that was with them. I was very scared while running, but from the moment you survive, these events all stick with you as adventures.

When we were in the jungle at the top of a large mountain, after days of trudging through the dense jungle and swamp, with dense fog rolling in around us and our guide cutting his way ahead of us with his machete, we suddenly noticed him drop his machete, suddenly jump back holding his hand. It's very quiet. Only frightened looks. Two tiny wounds on his arm - we knew immediately it was a snake bite.

There is a set protocol to follow: sit the person down, use your satellite phone to call for help, and inform the center.

We have a so-called spot device that sends GPS signals to the rescue unit. But our guide’s condition was deteriorating rapidly, his mouth was trembling, and he was starting to go pale. We didn't have any vaccine because there is no antidote for all kinds of snake venom, but if we accidentally administer the wrong vaccine, it could kill the victim. Also, these vaccines require refrigeration, but we can't carry a cooler with us. Snakes like to rest undetected under huge tree trunks, and as soon as you step on the ground, you could easily be bitten on the ankle by a waiting animal. The most dangerous thing is what we can't see. If a mamba or a Gabon viper bites you, you have four to five hours at most if you don't get an antidote. This danger was part of our job, we had to live with it. We were in the Congolese wilderness, about four hours from our accommodation, which was also four hours from the base camp at the foot of the mountain. Two hours from the foothills was the nearest settlement, which was a twelve-hour drive from the nearest hospital. If you are bitten by a dangerous poisonous snake there, the time you have is only enough to call your family and say goodbye. That is if you are able to call them because satellite phones don't always work below the canopy layer. Sometimes my wife didn't hear from me for days because I simply couldn't make the call. After a snake attack, you have to take a photo of the animal to know what kind of snake bit the victim. I did manage to take a photo, while the other geologist in the team was trying to find reception, but it was very bad, so all they could hear in camp was that there had been a snake bite. When I got back from taking photos, I saw the victim throw up. There's nothing else to do, you start praying. Prayer brings relief and hope even in the jungle.

The guy used the tribal remedy for snakebite, which means that if you get bitten by a snake, you take a leaf, form a funnel, pee in it, and drink it.

Drinking his own urine on an empty stomach and the stress made the poor boy so sick that he started vomiting. Of course, this tribal "cure" did not live up to the hopes. But he survived because the snakebite was a so-called dry snakebite, so no poison got into the wound.

The lines from the movie Troy echo in my ears: "The gods envy us. They envy us because we’re mortal, because any moment may be our last. Everything is more beautiful because we’re doomed." My time in the jungle has contributed a lot to my personal development. There, you learn to manage your fears, face them, honor them and make peace with them. In the jungle you are vulnerable, nature is still the master, you have to play by nature's rules and understand: man, be humble! I have understood that we must never look outside ourselves for the source of our fears, but within ourselves, and that the biggest fear of a man is themselves, that they are left alone with their thoughts. I once wrote a diary because it helped me to organize my thoughts. Nowadays I don't write them down, but at the end of the day, I think about what happened to me on that day. I give thanks for the day I had, I give thanks even for the most obvious things. It helps me focus on the good, creates inner peace, and helps me through the difficult moments. There are many situations in human existence that bring us to our knees, and we need a handhold. As I stood there in the middle of the jungle, like a madman rushing to his doom, I realized that I was surrounded by a wonderful world. After a while, my eyes got used to the darkness and I began to see. I saw many small creatures glowing around me, different kinds of mushrooms, butterflies, and fireflies. Suddenly I saw the world around us as beautiful and magical as I had never seen it before. A sense of wholeness came over me.

On one occasion, our guides and I were knee-deep in a swamp, exhausted after a day's exploring, when the road suddenly ended in front of us, revealing a huge gorge with two waterfalls swelling with primeval power. Even our experienced guides were unfamiliar with the area, and it was a fantastic experience to find that no one had ever been there before, not even the locals.

I quickly named the waterfall after my wife. My goal was fulfilled: to go somewhere no one had ever been before.

Since I have a daughter, I don't go on such dangerous and long trips. Today, the thought of death scares me, maybe because of her. There is so much I want to pass on and tell her. And I want to prove to myself, too. Since 2016 I have been very consciously building my career as a mineral photographer. It doesn’t feel like work for me, it recharges me, and gives me a sense of creation. Every photo I am proud of is feedback to me that I can do it, it's just a matter of practice. It is important for me that when I put a picture in front of the viewers, I know that I have put all my skills into it. If I feel that I haven't, then I try to photograph that piece again, and I start again. Sometimes it takes me an hour, sometimes a day to get a mineral photo. And although sometimes I still dream of the rainforest, sometimes I still think wistfully of returning, now I feel I've reached my goal. For now, I don't want to go to dangerous places, to disappear in the jungle for months. Maybe when my family says I've been home long enough. (laughs) My adventures in the jungle will always be my teachers, the ones that taught me who I am and helped me dare to fight the battles with myself.

The story was written by Emese Kosztin based on the memories of geologist László Kupi.