“The fact is, you should be exterminated! – the fates of priests after 1956

In the wake of the crushing of the 1956 Revolution until late 1957, that is, in just over one year, nearly 20,000 people were arrested, 180 of them were condemned to death for political reasons, and 110 ‘56ers were executed. Béla Biszku gave his assessment to the Political Committee of the Hungarian Socialist Workers Party at its session on 10 December 1957, noting that “there are many mild convictions for political offenses and relatively few physical exterminations.” In this article, we remember the victims of retaliation who came from the church.

On 27 December, the second son was born to the Brenner family, who welcomed the infant János as a Christmas gift in the Year of Our Lord 1931, in Szombathely. Both parents were well aware of what the arrival and raising of a child involved since the mother, Julianna, was the sixth child of a family of twelve children, and his father, József, was born the tenth child of his parents. János Brenner had a younger brother as well and all three boys were ordained priests. Snapshot of the Brenner family in 1956: the two parents and three grown boys in formal black – not only do the priest’s collars of the boys shine white from the neckline of the cassock, but also the smile of their mother, Julianna Wranovich. But what mother wouldn’t be delighted knowing that she had brought up three boys, each of whom dedicated his life to the service of God?

The photograph captures perhaps the last happy moment – but it is also possible that the shadow of the cross was already cast in the light of the life consecrated to God. The next image from the family archive is a surplice soaked in blood – the white linen absorbed the blood pouring from stab wounds as if it had been dyed using the batik technique.

On the night of 14 December 1957, János Brenner was lured from the Rábakethely rectory to see a ‘dying’ person. He left alone, walking along the unpaved way called ‘mass road’ towards Zsida. He had no idea that a group was lying in wait for him, while others kept watch from their hiding place in order to cut off his escape route if necessary. He was stopped on the pretext of a check and when he unbuttoned his winter coat to take out his documents, he was attacked by several people.

The athletic chaplain who was in good physical condition put up stubborn resistance but his attackers held him down and he was stabbed to death.

One of the attackers levelled a huge blow to the skull of Father János, which in all likelihood rendered him unconscious. They continued to hit and stab him even when he had fallen to the ground, and by the time the residents of the nearby farm, awakened by the clamour of dogs barking, arrived at the scene the murderers had already accomplished their evil deed. Their tracks were obscured in the mud.

“Aunt Málcsi, the morning is so beautiful! I could embrace the world!” This is how János Brenner greeted the woman making his breakfast on the morning of this fatal day. And what was his sin in the eyes of the communist authorities? The purity of his soul, his radiant personality, with which he attracted numerous people to the church.

“He is basically an intellectual type, somewhat inclined to rationalism and pessimism. Given his fortunate harmonic aptitude, in which the heart also has a place, he happily bridges differences. He is a keen-sighted critic but his inclination towards positive activity and modesty never made him offensive. He is hugely gifted and of a sharp mind. He is one of the most talented seminarians. He is a mature individual who acts in a manner consistent with a true priest of today. His warming and intelligent personality had a good influence on his fellows. He copes in all situations…” This is how his superiors characterized him before his ordination.

“My brother died before Christmas. Before he died, he sent a Christmas tree and a letter to our parents, in which he said that if the tree was not to their liking, then he would send another one. The Christmas tree arrived and the news that János had died followed a couple of days later. Ever since then, our parents have never put up a Christmas tree. We only ever had a Nativity scene at Christmas,” said József Brenner, great provost of Vasvár-Szombathely chaplaincy, speaking to Magyar Kurír at the time of the beatification.

János Brenner, martyr of the Catholic Church beatified in 2018, is perhaps the best known of the Christian martyrs of the communist regime in Hungary, but there are many more besides him.

Another happy family picture from 1954: a couple and three pigtailed and ribboned girls stand smiling in the garden of the Levél rectory. The youngest blonde girl bends over with affectionate love, cradling her doll in her arms. Although the picture is a little faded, time has not diminished the vivacity of the cheerful smiles playing on the faces, nor the relaxed movements; the harmony, the intimacy radiate from this posed picture across the decades and right into the present. The father of the three little girls, Reformed Minister Lajos Gulyás, became the only clerical victim of the retaliatory machinery of the Kádár regime to be sentenced to death and executed by final judicial order. Just as János Brenner was warned by his bishop of the likelihood of violence on the part of the authorities, so Lajos Gulyás was similarly warned by Lajos Máté, state security lieutenant, border guard officer, whose life had been saved by Lajos Gulyás from an enraged crowd after the Mosonmagyaróvár massacre. However, despite these warnings both János Brenner and Lajos Gulyás stayed at their post and continued to serve their communities.

After the formation of the Revolutionary Workers’-Peasants’ Government of Hungary led by János Kádár, Gulyás also came into the cross-hairs of the reorganizing repressive bodies. In December 1956, a house search was conducted at the Levél rectory, and then in early 1957 a highly slanderous article was published in Kisalföld, after which his wife and several colleagues made strenuous efforts to persuade him to leave the country.

He helped many escape, but he stayed although a horse-drawn carriage was waiting for him in front of the rectory. “A Hungarian does not leave his homeland! I’ll go to the gallows with pressed trousers!” he said to his wife.

He was arrested on 5 February 1957, exactly when he was celebrating his 39th birthday with his family. He was not sentenced in a church trial: during the procedure conducted against Gábor Földes and his fellows, he was assigned the role of ‘church reactionary pastor’. Lajos Gulyás was executed on 31 December 1957, two weeks after the murder of János Brenner, in the courtyard of Győr County Prison.

The death of Lajos Gulyás carried the following message: if somebody who saves the life of a border guard in the midst of an angry crowd can be executed, then anybody can become a victim of reprisals. The 1957-58 period served – in the words of Kádár, “with fire and sword, machine gun fire and prison” – to make absolutely clear for everybody that the state would ruthlessly take action against everybody considered an enemy of the regime.

As one interrogation officer put it bluntly to one of his victims: “Look, our job is now to stand the young people’s democracy on its feet, and everybody knows full well, as you do, too, that you priests are the greatest enemies of this democracy. The fact is, you should be exterminated!”

It is not ruled out that they knew the biblical passage: ‘Strike the shepherd, and the sheep will be scattered.’

Gyula Csaba, minister of Péteri, one of the martyrs of the Lutheran church, was not killed after 1956 but instead in the chaotic situation prevailing immediately after the war, in 1945. He was dragged from his bed and taken away in the early hours of 1 May. Some witnesses say that his eyes were put out, his tongue was torn out and his corpse was defiled. The words of Pope Pius XI were proven correct, who wrote in his encyclical on the dangers of atheistic and materialistic thought: ‘If people consciously steal the idea of God, their passions will explode unbridled in the darkest barbarities.’

We also have to mention Bishop Zoltán Meszlényi, who died a martyr on 11 January 1951 as a consequence of torture in the Kistarcsa internment camp. He was buried in an unmarked grave and his relatives were only officially informed of his death years later.

Thus, the process that reached its fulfilment in the 1950s, and then received new impetus in the reprisals after the 1956 Uprising, actually started as early as 1945.

Amongst the church victims of communism there were some who had to dig their own graves, some were executed by being shot in the back of the head, others were beaten to death, some were buried in trenches, others were thrown into former gravel pits used for bathing. For example, Pál Szekuli, chaplain of Öskü, died in suspicious circumstances; his body was found in the well of the vicarage on 7 December 1957. Károly Lajos Kenyeres was attacked by six or seven people in the early evening of 28 February 1957, when he was cycling home to Tiszavárkony after a religious instruction class. He was brought to the ground with a stretched wire, beaten, but they could not kill him so he was dragged to the Tisza and shot. His bicycle was thrown in the water, his body was hidden in the bank of the river that at that time was at a very low level and then earth was piled over him. When the family started searching for him the police put it about that he had fled abroad. Béla Pap, Reformed Minister of Karcag, disappeared in the Bakony in mysterious circumstances in August 1957.

And how long did the reprisals last? Piarist monk Ödön Lénárd was the last church prisoner to be freed following the personal intercession of Pope Paul VI in 1977. ‘Seminarist, high priest, parish priest, all soutaned swindlers, but there are still lampposts, but there are still lampposts’ – this satirical epigram scrawled on a street poster was read by Tamás Fabiny as he hurried to the ordination of a priest, in 1982.

The hatred stirred up against the church, the priesthood and religion proved to be a long-lasting poison.

Even though in the days of the revolution the churches did not play a leading role, it does not by any means mean that they didn’t have an important part to play. Besides the fact that the words of Cardinal Mindszenty, the Reformed Bishop László Ravasz and Lutheran Bishop Lajos Ordass pertaining to the revolution come to mind first and foremost in terms of the churches’ position, it is worth remembering the faithful witnesses of Christ’s teaching who became martyrs – the good pastors who gave their lives for their flocks.

At the same time, the identities of the murderers themselves mostly remain vague. Several, others, a group – that is all we know about them. Their tracks were obscured in the mud, their names were not noted in the pages of history. However, the memory of martyrs shines like a star. After all, the blood of martyrs is the seed of the church.

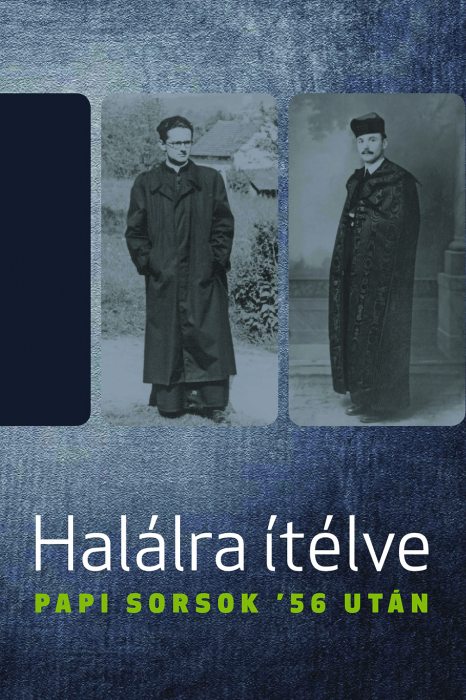

The book ‘Halálra ítélve. Papi sorsok 1956 után’ (Sentenced to Death. Fates of priests after 1956) can be purchased or read online at kiadvanyok.neb.hu.