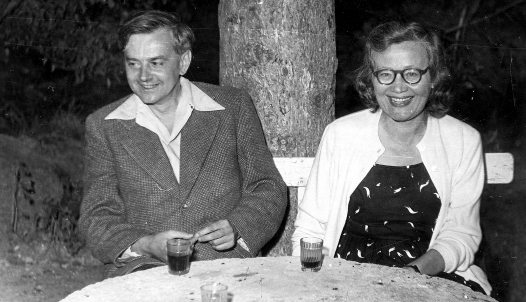

Miklós Papp: the mid-life ‘crisis’ is the natural path to maturity and development

Previously referred to as midlife panic, it was basically identified with the behavior of men in their fifties flanging with a young girlfriend. Fortunately, the phenomenon of mid-life crisis is now known to affect and excite almost everyone from the '30s' to the '50s'. We try to get away with it, and when we are in it, we look for coping strategies. We tend to look at the big crises in our lives in a negative, pessimistic way when the end of something can turn out to be the beginning of something better. I spoke with Greek Catholic priest Miklós Papp, head of the family theology institute of the Sapientia College of Theology of Religious Orders, about this period of life with its complex spiritual events.

Nobody escapes? Does the much talked-about mid-life crisis get everyone sooner or later?

“Developmental psychology categorizes the life of a person into approximately eight major stages. The role in life of a teenager is different to someone in their forties. The joys and troubles are different. The current of human life cannot be stemmed, it cannot be arrested by violence or ideologically, therefore the great changes in mid-life cannot be avoided either.

“Unfortunately, this is often called a ‘crisis’. It is necessary to see that this is in fact a ‘normal’ change. The end of every stage of our life is a crisis because we grow out of the lifestyle we have enjoyed so far and we have not yet grown into the new, but this is not bad: growth, maturity are the natural paths of development.

“The maturation crisis should be used for good: quit certain things from an earlier stage of life, mourn, and open towards the new with interest. ‘Crisis’ can be used for purification, forgiveness, sorting out, but also for discovering new energy, openness, learning. So a good ‘crisis’ can be a springboard and this is particularly true since the crucifixion of Christ.”

Is there always some great loss – partnership, financial, health etc. – in the background, or on coming into their forties do people instinctively draw up some kind of reckoning?

“Jung says that the first half of life is about collecting: when young, we ‘acquire’ a profession, qualifications, a household, children, cultural elements and money – in the second half of life it is not possible to live according to the same ‘collecting’ programme. Then comes the profundity. It often happens that somebody doesn’t want to, or simply cannot, step onto this narrower pathway, but instead wants to return to his/her twenty-year-old self and restart the ‘collecting’ programme. New companion, different religion, cosmopolitan lifestyle, untried things… Of course, these things can anaesthetize for a time but the deep-seated ball-bearings of our life will not allow us to lie to ourselves forever.

“You cannot run away from the big questions of mid-life: rather, you should embrace them boldly, and especially go after those who have moved on well.

“I don’t like using the expression ‘instinctively’ for spiritual matters. Instinct operates at the physical, biological, animal plane. The Soul rather ‘inspires’ one to the great questions, insights, profundity. We can be confident that the Soul leads everyone in every stage of life to the true happiness of the given age – but this never happens instinctively, mechanically, but instead in free, prayerful cooperation.”

The intensity and duration of the mid-life crisis differs according to the individual. What is it that determines how long it lasts and how we get through it?

“It depends on many factors. Firstly, we don’t drop into mid-life ‘innocent as a new-born lamb’: the big question is what we did earlier. To what extent did we resolve our earlier tasks in life, how many unfinished important matters did we put off, and even how much burden and sin did we amass, something that is not so easy to settle? Good models are very important: don’t chase after false prophets but seek out the true ‘elite’ who have gone ahead correctly. Man is a social being: good friends, long-lasting relationships, family are precious for us. Whoever possesses these has a bulwark in times of crisis. Spiritual maturity is essential: for Christians, prayer, the Bible, services, a spiritual leader, theology, ethical learning. According to Jung, an unsettled relationship to God always lies behind states of disorder cropping up in the second half of life. It may be that the problems appear in the guise of family, profession, psychology, culture, but Jung was of the belief that the root of these was frequently to be found in neglect of one’s relationship to God and insufficient spiritual life.

“Someone is smart who is smart in progress, that is, they experience the joy of every stage of life, they are capable of bidding farewell to a past stage of life and are open to the next.”

The false life-ideal whispered by advertisements and social media only amplifies this but fundamentally, why are we so afraid of the passage of time?

“One of the components of the mid-life crisis is the passage of time. It is like when you reach the top of a peak and there is no more going up, just down. You can see that you will not live as much as you have already. You see roughly what opportunities there are left to establish a family. You suspect what levels you can still reach in your career and what will be unattainable. You start to be dumbfounded at all those things you’ve never seen, never experienced, never tried, places never reached. And you’ll begin to glimpse the likely health difficulties, too. The passage of time is a hard press indeed.

“According to a German moralist, Klaus Demmer, the person who has not come to good decisions (good companions, educators, common sense, religion, ethics, culture etc.) will be forced by the press of time to make major decisions. The passing of time must be taken seriously. The great opportunity for Christians is that Christ revealed the entirety of time, the way in which history, and in it my life, moves on. This way, we can live all stages of life according to these eternal perspectives, we can handle opportunities and lack of fulfilment. We have to realize that the Christian faith is protective: it helps one to live in a true way in every stage of life and it represents a protection factor at times of crises, during the mid-life ‘crisis’.”

In the optimal case, a well-functioning domestic relationship can be a refuge. But what is the situation if the mid-life crisis crashes on the husband and wife at the same time and they both feel that the other is to blame for their unhappiness?

“In the optimal case, we marry for better or worse, that is, we can be companions in times of crisis as well. It may be burdensome if the ‘stars are misaligned’ at the same time but the opportunities in this must also be recognized. One can be more empathetic in understanding how the other feels. Joint steps can be sought out which will help both sides. Common friends can be mobilized. New habits can be taken up together, the partners can immerse themselves spiritually, they can also attend a learning course together.

“Blaming each other is a massive trap.

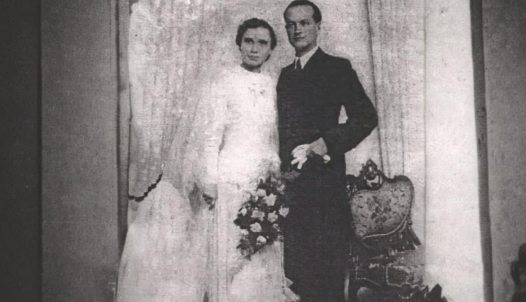

“On the one hand, there will certainly be some truth in it; when we marry, we do not take a god as our partner but a person with all their faults – however marvellous a being they are. Through one-sidedness, we caused a lack of fulfilment in our spouse: because of me, he/she did not become what he/she wanted, never managed to get where he/she wanted, his/her life didn’t become what he/she wanted, and this must be humbly acknowledged. The person who has not become reconciled in the course of life can truly accumulate a lot of dissatisfaction and this may reach boiling point at mid-life. So my advice is: humbly acknowledge that we have contributed to the lack of fulfilment of the other. Although we shouldn’t just look at this, we have to see how we developed each other, how much joy we had, how we took each other towards salvation – but it is good to reflect on the lack of fulfilment. A part must be let go, but maybe there is something that was a long-held dream of the other, and it would be great to fulfil that. This is how I took my wife to Venice after promising her we’d go for 20 years.”

It is a sad fact that nearly a half of all marriages end in divorce. When it appears that it is all over, why is it still worth carrying on?

“I would say just two things about the high number of divorces and the degradability of relationships. On the one hand, there is a dreadful lack of placing theology more at the centre of our lives. Theological truths cannot be footnotes at major moments of crisis in our lives; instead, they have to be the engine, the leading force, the inspiration. It is sad when we reach major decisions on the basis of instincts, desires, fears, or even merely at ‘humanist level’, on the basis of psychological or sociological aspects. Theological truths offer strengths, perspectives, alternatives, models of coping. They help one live.

“Of course, one is tired by the middle of one’s life if one wants to run only with human strength! A friend of mine who runs marathon distances said once: in order to run the marathon, one only needs enough muscle strength to do half the distance. Spiritual strength is needed for the other half. The same is true of life: it’s not easy to run to the end just using human strength.

“Theology is able to bring in certain aspects that purely secular sciences cannot, thus it is capable of answering the question ‘why is it worth persevering?’ in wider frames. Those for whom this horizon opens can take wing and fly. The other important aspect is that we talked ourselves into major decisions: that is, there is no such thing as an atomized ‘me’ who enters into a decision and then can step out of it without losses. If I talk ‘myself’ into a major decision, I identify with it, then by reneging on the decision I give up on myself, too. I must say that you should stick to your major decisions because they are who you are. I consider the expression ‘dynamic loyalty’ to be important: loyalty cannot be static (we keep doing the same things we did 20 years ago…), it must be dynamic. Decisions reached at one time must be increasingly allowed to unfold: from a mustard seed one can grow a large tree with a fine crop. The question of God comes up particularly keenly especially around mid-life; responses to questions of the passage of time, the meaning of life, life after death cannot be avoided. It is important for everybody to look into the eyes of God in a matured state: having shed the childish-youthful devoutness and non-devoutness, and relate to God as a mature adult.”