”It is important that they take on work and responsibility, in exchange for which we can help them” – We visited the Roma community in Rimóc

"Lóránt Vanya, coordinator for public employment, receives the “Presence” (“Jelenlét”) Award" - announced Szilárd Lantos, professional director of the Hungarian Charity Service of The Order of Malta’s program for emerging villages, on the stage of the Uránia National Film Theatre recently. I listened with interest to the laudation, which revealed that the honoured person had previously been a CEO who left the Private sector to join the Maltese team and then turned an abandoned, weedy hillside in Nógrád county into a productive one. In doing so, he provided jobs for dozens of Roma people who were unable to find work in the labour market. As Lóri took to the podium, I watched the glittering eyes of the audience and gave myself over to the echo of hands pounding on my eardrums, coming for a man who deserved a round of applause every day. I knew immediately that I had to meet him and the community in which he worked. "We should go to Rimóc...", I typed into my phone. "OK. Where is that?" - the message came soon after.

"We're almost at Hollókő, it's not far from there", says Laci, as his photographer's gear keeps bouncing at every bump on the road. I sit shotgun in a soft, patterned sweater, leaning my elbows on the edge and staring out the window, enjoying the way the sun's rays stream around my face as we wind our way down the road.

"This is a nice village," I say appreciatively, soon after we pass the Rimóc sign, and then the church, the shop, and the brand new sports hall. "There's even a mansion here. Like a hacienda. It's amazing," I point out the window, wondering if we're in the right place. "This must be it," Laci says, as the concrete road runs out from under us and we arrive at the site, which is home to about a hundred families.

The houses are smaller and older than the ones at the beginning of the street, and many of them have half (or all) of their plaster already fallen off. Six-eight children walk along the roadside with young, barely grown women, one of whom is pushing a pram.

A dog spots our car from a distance and approaches us, barking wildly, indicating that this is not our territory. It may bark at every car in the same way, but it may also have a good sense of spotting strangers. "We come in peace," I mutter under my breath as we leave the angry dog behind.

"Green is the forest, green is the mountain"

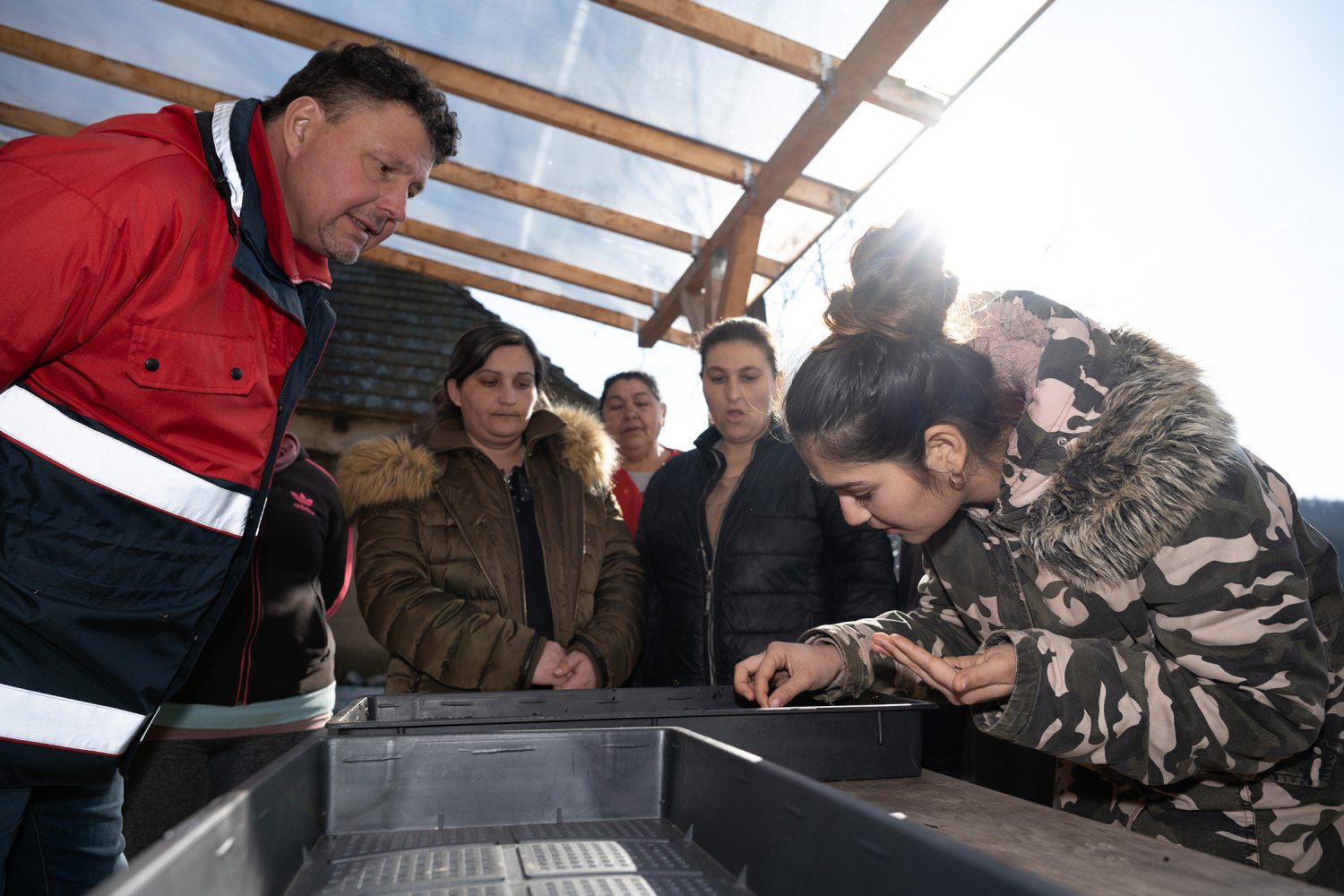

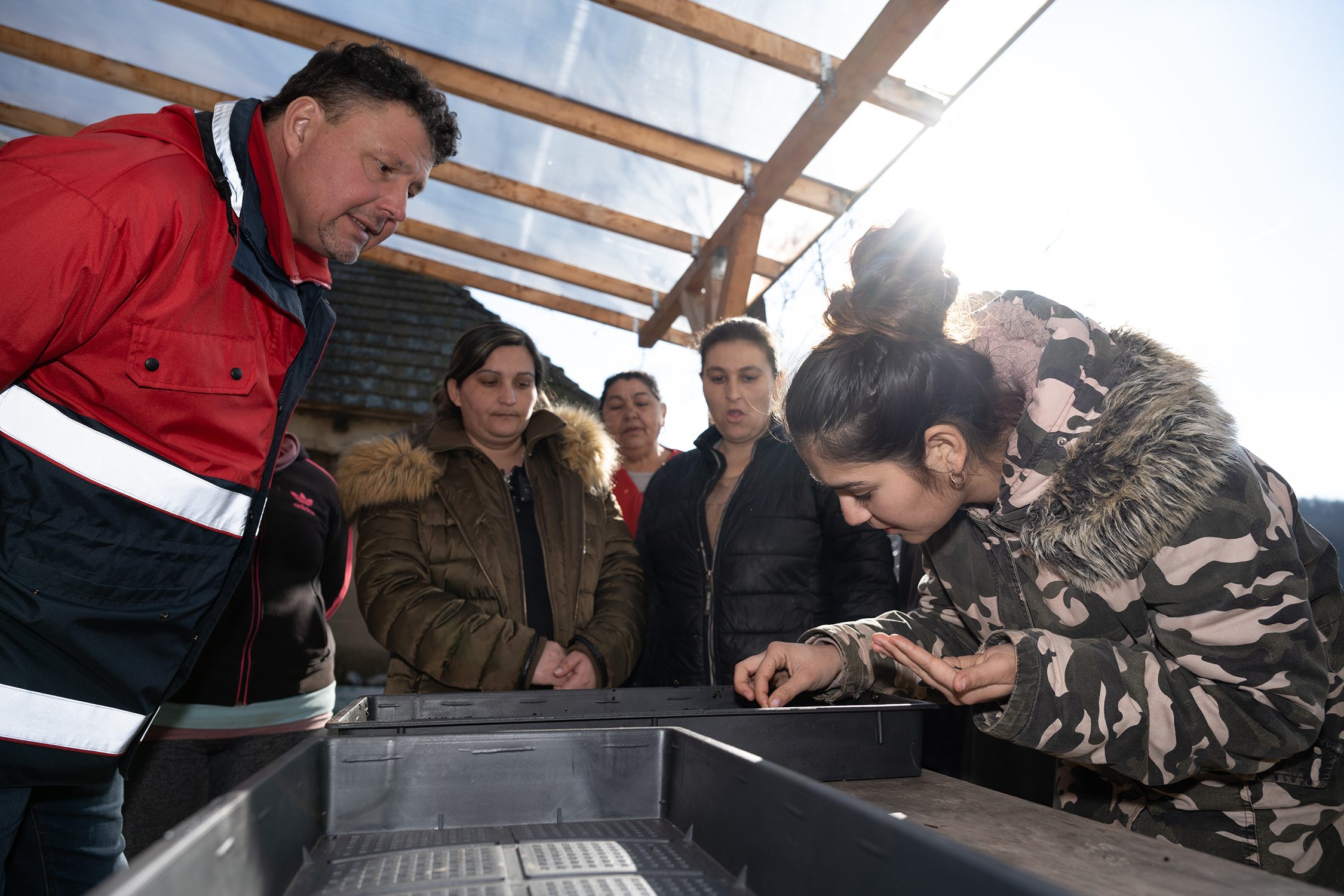

Men and women gather in front of our destination, the Maltese Presence House in Rimóc. We greet them with big smiles and ask where we can find Lóránt (or as they call him here: ‘Lóri’). "The Boss is in the back", they direct us, and soon we see Lóri in his big red Maltese coat explaining something about the land to one of the workers. He waves to us, pats the other man on the shoulder, and then ushers us into his office. He offers us brown tea and snacks. A beautiful woman with long black hair lives next door, she has been involved in the program from the beginning and loves working here, and she seems to understand the people.

Lóri explains that this building was bought by the Hungarian Charity Service of the Order of Malta (commonly known as the ‘Maltese’) and that on the one hand, the staff is always present, and on the other, the place provides washing and bathing facilities for the people. It's winter, and the landscape is still very gray, but in spring the hillside is green again, with twenty-one people working every day, and much of the farming produce is donated. "All pieces of land are all ascribed to a person," Lóri tells us, pointing out that this way people can understand responsibility more easily and can love what they do. There are always people who drop out, of course, but it is also true that in Rimóc there is now a strong 'core' of public workers who look out for each other.

From private sector to Charity Service

Lóri, the coordinator has been working for the Maltese Charity Service for three years now. Ha had been the CEO at his previous job, but as agriculture – something he loves so much – was becoming increasingly peripheral to the company's activities, he decided to change jobs.

Before he took over, about half a hectare of land was abandoned, but since then, thanks to the hard work of the workers, it has grown cabbage, carrots, onions, parsley, peppers, tomatoes, and more.

"Anyone can do it. The goal is to try to help ourselves to be self-sustainable. One of the key principles of Maltese Charity Service is to give in a way that requires work from the receiver’s part, too. When we first came here, we asked the people living in the segregated neighbourhood and tried to find out what most of their problems were," explains Lóri the first step of their diagnosis-based work.

It soon became evident that the biggest problem in Rimóc is employment, and more specifically the lack of it. Some of the people living here have not finished primary school, which is a basic requirement for factory work. A survey of adult education was also carried out and it became clear that there was a need for further education, but that it was a long, complicated, and costly process to organize because it had to cover logistical issues such as travel. When I ask him about the trust he needs to do his job, Lóri confirms what we had suspected before: the process of building relationships cannot be described in words, and taught, as there is no tried and tested recipe. No one knew him before, but thanks to his openness and goodwill, he is now allowed into any house.

The lunch break is over and more and more people arrive at the house and start chatting. The "Boss" is really accepted, even loved! This is immediately obvious to an outsider like me. Today's task is to make regular cubes of potting soil in which they will sow onion seeds.

"Today machines do everything, so we have no work"

While the girls are molding the soil, I approach two nice guys to ask them about life here. "I have three kids and we've lived here for a long time. These aren’t bad people. I’ve just started, but I can see that everyone is very cooperative. I used to work in construction, shuttering, but there wasn't always work," explains the young man, who everyone in the community calls Kongó or Kongi. This nickname was given to him as a child because he loved climbing.

Kornél, an older man, also joins us. We had met him and his daughter earlier on the top of the mountain when Lóri showed us around the segregated neighbourhood. His enthusiasm completely overwhelms me, flooding my heart with warmth as he explains. "I used to live opposite there," he points to the barren hillside, "my mum and dad used to live there, but then the water came in and they had to move.

Many of us were born here in one of the houses in Rimóc, and I was born there, right opposite of us, I was five kilos! Unfortunately, the old people have already all died.

When I was a child, there were no machines, only scythes and haystacks. Nowadays, machines do everything, so we have no work..." says Kornél, then returns to planting onions.

As I continue to ask the men questions, we find something in common: it turns out that all three of us like music, and Kongó and I even like to sing. "Sing for us! Do you have a nice voice? Now, why are you shaking your head, are you shy? What kind of music do you know? Do you know Béla Csóré?" - asks 20-year-old Peti, who says it's his first job and he likes it here because the work is not bad and the boss is "cool". "I don't know Béla Csóré, but I'll certainly listen to him," I vow to the company.

I go into the house to sit down for a while and sip the hot drink kindly offered. As we chat, it becomes immediately clear to me that they are as curious about me as I am about them. Where did my name come from? What do I do? Have we met before? It is with great pleasure and curiosity that I talk to them, listening to them while I have a piece of fruit candy from a nice girl in my mouth. The members of the Romungro community in Rimóc speak a very interesting mixed language, that is, they mix Gypsy words with Hungarian. I ask the nice woman sitting next to me to teach me something, so I finally learn, for example, what "Dikh!" means (It means “Look!”)

Presence involves many things

"The point is to keep in touch. We are not an office, a bureau or a customer service. If I'm having breakfast and someone comes in and says there's a problem because, say, a letter has been sent by the electricity company, it has to be read then and there. Work is a good opportunity to ask them how they are, how the children are doing, or what's on their minds in life. Perhaps the biggest change so far has been in the area of debts. Many people are in debt, utility bills and goods credit are a problem, and people are often threatened with pursuance.

We help them interpret the letters, and draft their replies, our colleague provides consultation, and they have started to pay off their debts nicely. This is a very good thing!

But I'm also happy to report that I was recently able to take two young boys with me to the nearby town of Szécsény to an agricultural training course, which could give them a new chance to make a living" - says Lóri, who has two points that he loves emphasizing: one is breaking out of gastronomic poverty, i.e. incorporating regular, varied meals into their lives, and the other is the issue of quitting smoking.

He always has a good idea, he’s always full of plans, the most important ones printed out and pinned up in front of him so that he could keep his eyes literally on the goals. "We have just bought a piece of land where we plan to build an organic farm. This could be a self-sustainable place where we grow crops in deep mulch, where we don't use chemicals and if we build a vegetable processing plant, we could employ people full time," he tells us.

When I ask him about the Presence Award, Lóri smiles modestly. "Of course, it can be motivating if you get such impulses from your workplace, or when you're told in a meeting that we're going in the right direction, that we have results. But it's also a kind of recognition when I see that employees like coming here, like working here," he adds.

Life in Rimóc is not a fairy tale: if you don't put your heart and soul into the program, you can't expect flexibility, and there are people who do so. "You can't put up with people not wanting to be here for long because you’ll soon have enough."

"It's important to maintain discipline and the work schedule because everyone here is paid the same. I can't let some get away with no work because by doing so I'm disrespecting those who work properly and that’s not what they deserve," the coordinator highlights.

The presence also includes the so-called "vegetable garden" program, which means that people take home what they've learned in the public employment program and put it to good use in their own gardens so that they can grow vegetables at home.

"If someone's garden hasn't been dug up for ten years, or if we can't even talk about a garden, only a yard, we ask them to dig up a small piece, and then we go to help with electronic hoes, and seeds, but it's important that they take on the work and responsibility, and in return, we can help," explains Lóri.

Several villagers are proud to show off their house and what this year's vegetable garden will look like, as they are looking forward to making it better than last year. Because it needs tending, a garden requires a long-term commitment, which is not easy for everyone to make.

The end-of-winter work is still in full swing next to the house, with rows of small clods of soil that will soon sprout onions. Someone starts singing loudly "Eight hours of work, eight hours of rest, eight hours of fun", and I join in the chorus, gesturing to Peti and Kongó to see if they can hear that I have finally sung for them.

The time of farewell, the promise of reunion

"You will write good things about us, won't you?" - asks Fuko, with whom I was earlier chatting in the kitchen about the cultural differences between Romungro and Olah Gypsies. I smile at him and pat him on the shoulder. Together with Lóri, the group is lined up by the fence, waving enthusiastically, and we are all very hopeful of seeing each other again. As we turn out of the village, in the car I type in the search keyword and my phone soon finds this:

“I live among gypsies. That's where my homeland is. There, where my lover’s voice flies" – I hear the singer’s voice. I smile, wondering what they will say when I come back to Rimóc in the spring, singing – among the seedlings – the songs of the legendary Béla Csóré.