Why is the Swiss William Tell on the playing-card? – Discovering the secret of the Hungarian deck

In Hungary everyone is familiar with the so-called Hungarian playing cards, this popular, unique, and historical Hungarian game where the cards, oddly, are decorated with non-Hungarian historical figures. We know little about the cards that were once in public use – they are all worn out, and the only one that the Hungarian National Museum had preserved in its special collection was unfortunately destroyed in 1945. Fortunately, there are some interesting facts about the history of the history of the “Tell deck” that we do know.

The first cards

The Buda Synod of 1279, for example, forbade priests from attending events where they played cards because it was considered gambling. The fight against gambling includes the story of St. John of Capistrano, who preached so successfully against it in Nuremberg that his followers burned nearly 40,000 dice, thousands of backgammon sets, and many packs of cards at the stake.

However, the fight against cards has never really won the day.

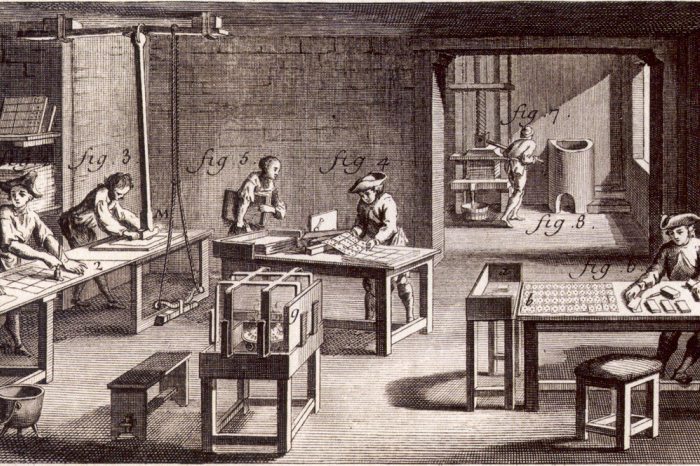

The new printing techniques of the 15th century made it possible to produce this game in large quantities at affordable prices, and while it was once a passion of royalty and nobility, it has since become a great source of entertainment for all social classes. Even King Sigismund and King Matthias played cards, but the first surviving domestic cards were made much later and came from a printing press: the binding plates of Gábor Pesti' s dictionary, which were probably made in the 1560s. Where there was a printing press, there was also a card painter.

Playful everydays

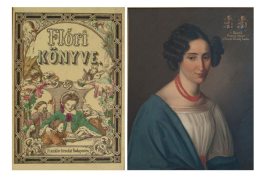

The card game thus began to spread slowly, reaching its heyday in the 19th century. By this time, artistic illustrations were being produced in Hungary, and card playing became an inescapable part of domestic social life. The card table and the card press, where cards could be stored to keep their original shape and rest until the next game, were an essential part of the home. In 1869 the First Hungarian Card Factory Limited Company was founded. Contemporary books, literature, and paintings show the importance of this game, but even works on manners always include a reference to card playing. The country gentry saw it as the best form of entertainment, as did the great men of the age. Franz Liszt, for example, was rather passionate about cards and played them every day, not for money but for fun whenever he had the chance. As one of his fellow musicians and fellow players, István Thomán, recalls, 'this musical giant of childish nature was quite unhappy when he lost.

and because of this we later made sure that he would always win”

But there was another side. At the turn of the century, the newspapers often reported on scandals, losses of fortune, duels, caused by the game. Kálmán Mikszáth wrote in his pamphlet "Kártya" (The Card) his thoughts against what he considered to be a more dangerous pastime than drinking pálinka. As he wrote, "The passion for playing cards has become so rampant nowadays that it can be described as the cancer of our society. It is the most burning wound threatening to destroy us. Armies of bloodthirsty kings, massed together, and engaged in deadly battles, have never killed so many men as the four painted men on horseback and the other eight on foot, whom we call 'kings', 'lower knaves' and 'upper knaves'. If we want to make mankind happy, let us first destroy these kings with their subjects." Fighting the king was a good call.

The Hungarian deck

This is what József Schneider appealed to. He was the creator of the best-known type of card in Hungary, the Hungarian deck, which began to spread before the War of Independence in 1848. It was fashionable at the time to put characters from literary works on cards, and this is what Schneider, who worked in Pest, did. He took a popular story about the struggle against the Habsburgs and painted that on his set of cards. Habsburg oppression was the reality of everyday life at that time, yet the Austrian censors could not object. The story was that of William Tell and the freedom fight of the Swiss people against the tyrannical Habsburg imperial governor Gessler and his henchman. Schiller's drama had made it into the Hungarian public consciousness (it was first performed in Kolozsvár (Cluj) in 1827), so everyone could understand the reference. The depictions of nameless kings continued an old card tradition, as did the allegories of the seasons on the aces. The lower and upper knaves cards, on the other hand, depict the characters of the drama, while the other cards show images with William Tell on them.

And on bell IX you can see the hat of Gessler, the Habsburg’s man, on a pole...

(The Hungarian deck has 32 cards, divided into four suits: acorns, hearts, leaves, and bells. The cards are numbered with Roman numerals from VII-X, followed by lower and upper knaves, kings, and aces.)

Dealing cards

So it is understandable why Hungarians who were forced to emigrate after the fall of the 1848-49 War of Independence took a few decks with them. Although it never became known in Switzerland, the Hungarian deck of cards appeared in Paris and Frankfurt in the second half of the 19th century. In fact, after 1865 it began to spread in the Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy. This was thanks to a major enterprise of Ferdinand Piatnik of Vienna (whose father was a native of Buda). The monopolistic company has, with some modifications, introduced the "Tell deck" to the Czech and Polish markets. For this reason, and because of the German parallels between the suits (acorns, hearts, leaves, and bells), it was long believed that this type of card was the invention of Piatnik. Until 1973, when an English collector and card historian, Sylvia Mann, bought one of the original cards, dated around 1835, with the name of József Schneider from Pest on it. Although Ödön Chwalowszky, also from Pest, created a Tell card at about the same time as Schneider, Schneider is still considered to be the first. His workshop was located at 55 Kazinczy (formerly Kiskereszt) Street in Budapest; in 1996, the Hungarian Talon Foundation and the Pató Pál Association, placed a commemorative plaque on the wall of this house, and 29 December was designated Hungarian Card Day.

Literature used:

https://www.kartya-jatek.hu/irodalom/

Jánoska Antal, A magyar kártya története, ikonográfiája, készítői

Perjés András, Kártyatörténet: A kártyajátékok és társadalmi megítélésük