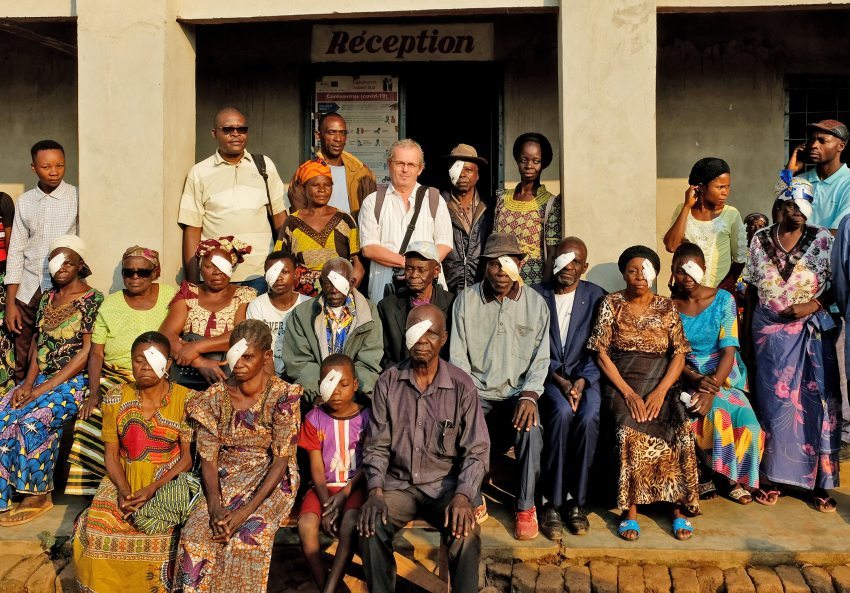

”Hi, doctor Rishar, remember me? You operated on me!” – Dr. Richárd Hardi, ophthalmologist, restored the sight of tens of thousands of people in Congo

Dr. Richard Hardi, an ophthalmologist who arrived in sub-Saharan Africa in the mid-1990s with a suitcase full of instruments, works in the poorest parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Besides his healing profession, he is a member of the Community of the Beatitudes. As a result of his work, a new eye clinic was opened last year in Mbuji-Mayi. In the Congo, cataracts, which cause blindness, affect many people and the ophthalmologist operates on 2,000 patients a year, including many children. Many of them have their sight completely restored. His small team sometimes drives days on bad roads to a mission, but he says it's his way of relaxing. Brother Richard returned home for a few weeks and gave an interview to kepmas.hu.

Where do you feel at home? In Congo or in Hungary?

My real home is in Hungary, and I miss it very much when I'm in Congo. But when I'm back home, after two or three weeks, I yearn for Africa. Part of what I fought for, for 27 years, has taken shape. While I am away, my friends there do the work, I miss them. On the other hand, many patients come to the clinic because of me, and they wait patiently for me. I come home twice a year for 4-6 weeks, I used to come only once a year.

Normally in missions, you have three months off every three years, but as an ophthalmologist that's not good, because science advances a lot in the meantime, and it's more useful to be informed more often about what's new.

When did you first visit Africa? Did you feel you had a job to do there right after your first visit?

In 1973. I was 15 when I moved to Algeria with my siblings and parents, my father had worked there as an engineer for five years. Algeria really captured us. Back home, I went to medical school and became a specialist, but I always had the desire to go back to Africa. You have to know that North Africa is very different from Sub-Saharan Africa. Meanwhile, in 1992, I joined the Catholic Community of the Beatitudes, which had a hospital in Congo and where they were very much looking for a specialist.

After graduating from medical school you arrived in Congo with a suitcase of instruments.

I had no idea what the conditions would be like there, Kabinda is a small town in the middle of the Congo, far from any big city. I took small surgical hand tools: forceps, scissors, etc. There was only one slit lamp and one ophthalmoscope. We started from scratch. I went from the city hospital in Tatabánya, from a well-equipped ward. It was a big step back in that respect, it was difficult to start again there.

I had binoculars, I converted them into a microscope, I operated with it, and I started asking and praying.

How do the medical profession and church ministry fit together?

I am a consecrated member of the lay branch of the Catholic Community of the Beatitudes. This means I don't have to live strictly in a monastery, I can be alone. I have a special mission. Almost all monastic communities in Africa undertake social work: education, or healing. The form a hundred years ago was that the missionaries came, set up the parish, started building the church, and put up a school. That's not the case now, but every diocese has a health office, and hospitals and health centers come under it. Jesus says, 'the poor will always be with you, but I will not always be with you'. A balance must be found between the life of prayer and the medical profession. It is not good if the ophthalmological profession takes up all my time.

You perform cataract surgery for the most part. Why do so many people in the Congo suffer from cataracts, which cause blindness?

On the one hand, there is strong solar radiation and UV radiation. The other reason is that there is no primary care, and the eye care is very poor. For a country of 100 million people, there are 105 ophthalmologists, that is one doctor for every million people, most of whom work in the big cities. In Europe, 8-9 thousand cataract operations per million people are carried out every year; in the Congo, 10,000 were carried out last year for every 100 million. The difference is noticeable. In children, it is often a genetic problem, with a much higher proportion of children living with cataracts in Congo than in Europe. When I worked in Tatabánya, I did not see a child with a cataract in five years. In Africa, I operate on seventy to eighty children a year.

A cataract operation is quite quick, it takes about ten minutes. We operate on two thousand people a year, 1400 of them have cataracts.

We are talking on 16 June, today is World Day for African Children. What chance do they have to see well?

It depends on the family, too whether the child's eyes will be amblyopic or completely healed. The child should go back for a check-up and wear glasses. If we operate on someone in a remote mission, the chances are lower that they will see well because we operate on them, but then we have to go home, and they would need regular care. After the operation, of course, they can see somewhat, but not well. They know the place where they live, and they can orientate themselves.

You started missionary work in Kabinda, but no longer live there.

I lived for ten years in Kabinda, a small town of 100,000 with relatively few patients. When peace came after the wars, more and more people came to me from other places, and I thought we should go too. Mbuji-Mayi, the capital of a diamond-producing region, a city of two million people is 150 kilometers from Kabinda. We first opened a small ophthalmology center there in 2006, and in 2017 we started building a new clinic.

You also travel to places far from your home in Mbuji-Mayi to heal. How should we imagine such a trip?

It's a big country, we're trying to cover three counties with 8-10 million people. We've seen patients come from very far away, but it's too difficult to get to us, or they're afraid of the city, they don't have the money. So we need mobile equipment, financial cover and a car. A big mission takes about three weeks.

On the last mission, we traveled for two days, stopping overnight, and the distance was only 250 kilometers. The roads are terribly bad.

But it also depends on what season you are traveling in. In the dry season, it may be easier to travel, but there is a lot of sand, which slows you down. To the most remote places, like Lodja, it takes three days. In the first years, I did everything, seeing patients and operating, but now I have six doctors, so I only operate using a modern instrumental method, which my colleagues are now starting to learn. On the missions, the crew needs two or three doctors, a head nurse in the operating theatre, a nursing assistant, an optician, and drivers. Because of long journeys, I now sometimes send them ahead and try to join them later by plane.

On your missions, you were sometimes asked by locals to fix a fridge or some other electric device.

For an operation, everything has to work: electrical wiring, generator, and so on. We usually go to a public hospital, where there is an operating theatre, but it is poorly equipped. I always go with two boxes of tools and I fix everything, it's in me somehow, it's how I was born. The locals then start bringing me other things to fix.

With the support of the Hungary Helps program, a new hospital was opened last year. How many years of work are there in this?

The clinic has been under construction for several years in Mbuji-Mayi, and the operating theatre was inaugurated in October. We first established the ophthalmology center in November 2006, and from there I started to gather the staff to build the clinic. We bought the land in 2013, after which construction could begin. For five years, the clinic has been owned by a non-profit organization, the director is an African doctor and my job is to provide the best specialist training possible. This is the program for the coming years.

How do you spend a working day? Do you ever not work?

For me, relaxation is when we travel, otherwise, I work from Monday to Saturday. I start the day with prayer at home at 6:30 in the morning, I'm at the clinic at 7:30, we talk about the day, and then the office hours with seeing patients or surgery start. I do most of the surgeries, and thanks to Hungary Helps we have managed to get very good diagnostic equipment, such as ultrasound, OCT (optical coherence tomography, an important diagnostic tool in modern ophthalmology - ed.), and lasers. There is no social security in the Congo, so everyone has to pay something for their care.

In the missions, sometimes someone is so poor that they can't pay anything. We have a fund from donations from Hungary, Belgium, and France, so in these cases, we help out from that fund.

It would be a disaster if someone came in blind because of cataracts and we didn't operate them because they couldn’t pay.

How do you see Sub-Saharan Africa and the Congo changing compared to when you first arrived as a doctor in 1995?

There has been an improvement, but unfortunately, specialist care has not changed. That is why I would like to train specialists, but it will take time. In Congo, there are only two big cities where you can get a specialist ophthalmology qualification. I work with general practitioners, teaching them ophthalmology. It is very important to train more specialists.

You regularly post about your experiences on your foundation's website and social media pages.

What we experience, I think, is both privileged and special. I walk in the jungle, I see the simplicity, the poverty, and yet the happiness of the children growing up. We do so little, yet what a difference we can make! The other day, I was taking pictures on the riverbank in Lusambo, when a little boy said to me: 'Hi, Doctor Rishar, do you remember me? You operated on me!" - he said. Then he took me to his dad, who was welcoming me to his house. African people are not easy to make friends with as white people. But in all this time, I've already made true friends.

Have you never thought about choosing the easier way and coming home?

I have lived through two wars in Africa, the first one in 1996 was psychologically harder, but at least they didn't shoot. Then came the second Congo war in 1998, which lasted five years. (The second conflict killed more than five million people, involving 12 African countries from Libya to Sudan to Namibia - ed.) There was a trench system around our town, it was mined and the rebels were stopped there. Anything could have happened.

I was the leader of the Catholic community at the time, we hold on to prayer very much. Missionaries are always committed to trying to work through conflicts locally.

We decided to stay. We stayed, and thank God we were not harmed in any way.

How do you imagine your daily life in 10-20 years? Have you made a lifelong commitment to healing the Congolese people?

I would like to see the clinic running well, with a secure financial and professional basis. Now I still have something to give: it is important to pass on surgical knowledge and practice that others can rely on. But what the good Lord has in mind for me in the long term, I don't know.

András D. Hajdú made a documentary about Dr. Richárd Hardi’s missionary work in the Congo, titled Szemtestvér ("Brother Eye"), which can be viewed here (in Hungarian).