The movie-like story of a Hindu-Hungarian aristocratic family and their Transylvanian heritage

People call him Count Gergely; Gregor Roy Chowdhury-Mikes, the majority shareholder of the Secuiana, an apparel manufactory in Kézdivásárhely (Târgu Secuiesc), has aristocratic roots both from East Bengal and Transylvania. The story of the Mikes family and the Zabola Estate, which was returned to them after a dramatic turn of events, is full of historical challenges.

The reclaimed estate

The wrought-iron gate of the Mikes Estate in Zabola opens onto a breathtaking sight. Not far from the entrance, to the left, the old riding stables catch the eye, the only major farm building not pulled down by the great-grandfather. It was the home of the most valuable horses of the once famous Mikes stud farm, which used to be an important source of income for the family. The magnificent interior, with its arches and columns, is evidence of a restoration that reflects the owners' affectionate and tasteful approach to the estate, with the light of former days of glory almost radiating from behind the weathered plaster.

The main manager of the maintenance and development of the estate is Gregor Roy Chowdhury, the son of Shuvendu Basu Roy Chowdhury, an aristocrat of East Bengal origin, and Count Katalin Mikes of Zabola.

Gregor, known locally as Count Gergely, was born in Austria. His mother, Katalin Mikes had been forced to leave the centuries-old family nest at the age of three due to nationalisation and miraculously made her way to Austria at the age of 16.

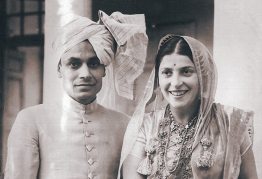

She met her future husband, Shuvendu Basu Roy Chowdhury, in Graz, Austria, and the two were married and became parents of Gergely and Sándor. These days, the former spends more time in Zabola – in Romania in general – after the restoration wrestling that began in the early 2000s resulted in the family regaining ownership of part of the ancient estate. It includes the old and the new castle with 50 hectares of the Zabola estate, as well as 3.5 thousand of the 13 thousand hectares of reclaimed forest. But only on paper, the forest issue has been tangled in the maze of the Romanian legal system for years.

In the footsteps of the great-grandfather

Gregor, or Gergely, has turned into one of Transylvania's most interesting businessmen, after becoming the majority owner of the Secuiana clothing factory in Kézdivásárhely (Târgu Secuiesc), which has a history of more than half a century. All his investments have been made with a single purpose: to raise the capital needed to run the estate. The businessman-count combination was inspired by his great-grandfather, Count Ármin Mikes, who built a new two-storey chateau in 1904-1905, connected to the old castle by a tunnel and a two-storey bridge. The original idea was to have guest rooms on the upper level and offices on the lower. As he eventually had a separate agricultural lodge and steward's villa built, all farming activities were moved there and the new castle was also used as a guesthouse in the 1930s. Old promotional brochures bear witness to the efforts to make the building suitable for tourism.

Ármin Mikes was considered a rather individualistic figure among the aristocrats of the time. An entrepreneurial count to the core, he set up a multitude of companies from Budapest to southern Romania.

Thus, for him, the Treaty of Trianon (1920) was a great blow not only because of the subsequent confiscation of property but also because, as a citizen of an enemy country in the First World War, he lost all his investments in Romanian companies, including a major railway project and its hoped-for benefits. In later years, he sought to rebuild his contacts in Bucharest, was the only Hungarian member of the Romanian Jockey Club, maintained constant contact with the Romanian liberal elite, and was regularly received by Ferdinand I and later by the Romanian King Charles II. Whenever a Hungarian economic delegation came to Bucharest, Ármin Mikes was a member of it. He made the most of those difficult times.

Fantasy in fabric

His great-grandson is also trying to make the most of the opportunities he has created largely by his own hands. "I've been driving a lot around Romania and seen a lot of fallow farmland. It was a time when you could get capital for farming, and farmland seemed like a sure thing. Initially, I rented a lot of small pieces to set up small farm units, and then I looked for agricultural companies in trouble. I ended up with a company in the Dicsőszentmárton area, and the business took off nicely, but I kept looking for something that would grow at a faster pace," he tells us the of the beginning.

When he was offered the textile industry a few years later, he was not interested at first but decided that the company in Târgu Secuiesc, operating practically under the owner's nose, could hold some potential.

"I thought there might be a change in trend soon: after the COVID-19 epidemic, a lot of companies would no longer want to have everything made in the Far East, they’d come back to Europe, at least in part."

"The idea worked to some extent, in the spring of 2022 I started negotiating the takeover of two German brands, and now we have an office near Hannover," explains Gergely.

Family relations in India

He had visited Transylvania several times as a child, but in those days, in the 1980s, they mostly went to visit relatives in Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca). He first visited India for a wedding when he was ten years old, and only after his father died in 2002 did he start to focus more intensively on his Hindu roots. Most of his relatives there now live in New Delhi and Calcutta, some of whom would prefer to forget the past, but some of whom are happy to remember.

It's easy to see a bit of fate in the way the parents met. The Roy Chowdhury family, like the Mikes, lost everything after the partition of India in 1947, when Hindu-Muslim strife divided Bengal into East and West Bengal. Gergely says it was only later, as an adult, that he began to "untangle" the threads for himself. On the one hand, there is an Indian family with everything for a comfortable, peaceful life, until in 1947 India was cut in two and the family had to flee the areas outside the borders. However, while Gergely and Sándor's grandfather, born in 1901, had then been living and working in New Delhi for a long time, many members of the family arrived in India with only one suitcase. The refugees from East Bengal received no compensation for the possessions they had been forced to leave behind, only land on which they could build a new home. Those who stayed have endured much persecution, but some are now successful businessmen.

To start afresh is also a legacy

Researching the past is now an important goal and part of Gregor Roy Chowdury's life.

He visits India and Bangladesh several times a year, keeping in regular contact with 30-40 of his more than 500 relatives scattered around the world.

Recently, a Bangladeshi business newspaper, The Business Standard, "discovered" the distant Bengali who is working on tracing his ancestors. And he found one of his cousins: he is now a chef in the kitchen at the Zabola Estate.

Here at home, expropriation continues, but now of his own free will: The Mikes family has declared a forest in Sepsibükszád as primeval forest under the Conservation Transylvania green biodiversity program, which means they have practically expropriated themselves. Starting afresh is a family legacy anyway. Count Ármin Mikes also bought forests in southern Romania, all of which were confiscated in one twist or another of history. When recently talking to an Indian relative about the forests that are still the subject of litigation, he asked how long this process had been going on. And when he was told that it had been five years, he said, almost consolingly, "We have been in litigation with the Indian state for 250 years."