“I saw my child lying on a table, covered with a sheet” – The story of Flóra Béry-Januskó and her little son with SMA

"As a senior in high school, I was diagnosed with a gynecological condition that gave me very little chance of ever getting pregnant naturally. I wasn't the type of girl who always played with dolls and knew at the age of ten how many children she would have, but it struck me. That's when I realized I really wanted to have kids. When I found out I was pregnant at 21, I couldn't believe it. Nor did my doctor. Then he did an ultrasound and told me there really was something there."

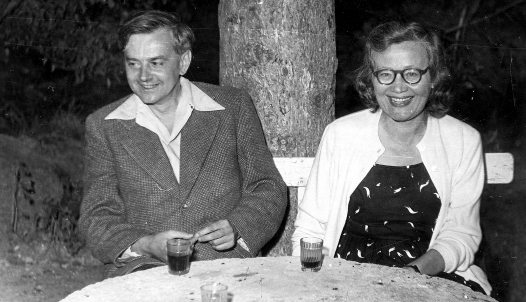

Flóra Béry-Januskó originally wanted to be a doctor, or more precisely a military doctor, because she saw this as a real life-saving profession. In high school, she studied biology and chemistry, but when her gynecological condition revealed to her how important motherhood was to her, she was unsure about her future plans. She decided not to sacrifice her youth to long years of university studies and a career in medicine. She eventually majored in security and defense policy. After graduating, however, she did not have enough time to find a job because she met her ex-husband and soon afterward found out that she was expecting a child.

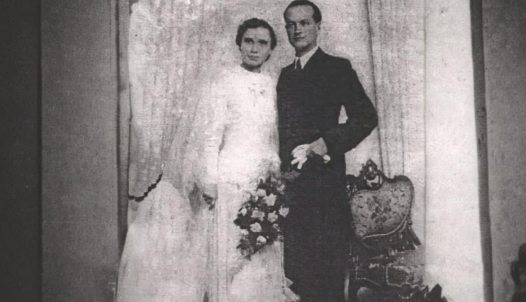

" We were very happy, Ábris was a real love child. There was no question of keeping him, even though it was all very sudden. I was already pregnant when I married his dad, but my realist self felt that I wasn't sure if this fresh relationship would last. We were already having difficulties during the pregnancy. We separated shortly after Ábris was born."

20 percent chance of surviving to one year of age

Flóra's life was turned upside down by her son, Ábris. During the pregnancy, there was no sign of any problems with the baby. They had several genetic tests to screen for common diseases, but doctors found nothing amiss.

Five and a half months after the birth, Flora noticed that her son could no longer do the things he used to be able to do.

But at first, he showed rapid progress: at two months he was already lifting his head, and not long after that he was able to put his pacifier in and take it out of his mouth. It was noticeable that after a while he couldn't do those. His motor development came to a complete standstill and he did not learn to sit up on his own.

Suspecting a musculoskeletal problem, Flóra first took Ábris to an orthopedic doctor, but nothing unusual was found there. They went to a physical therapist, and a physiotherapist, and went to a baby swimming course, but they all told her that everything was fine.

"When Ábris was seven and a half months old, someone suggested we go for a developmental neurological examination. There, the doctor told me at first glance that my child had SMA. When I asked him what that meant, he said there was an 80 percent chance he wouldn't live to be a year old. He said this in the style of asking someone if they like their coffee with milk or sugar."

To confirm the suspicion, Flóra and his son had to undergo several tests. But they did not complete the week-long hospital check-up, from where they left on the third day on their own responsibility because of an unacceptable event for Flóra.

"I couldn't go in for one of Abris' examinations. I waited in the corridor and when it was well over the necessary one hour, I knocked on one of the nurses' doors to ask if they were finished. She said yes, but she couldn't tell me where my baby was. Then I heard a baby cry from behind one of the doors; I sensed it was Ábris.

I opened the door and saw my child lying on a table covered with a sheet, and the specialist was explaining to the residents that this child had SMA and that if he didn't take the sheet off he would suffocate because he didn't have the strength to pull it off.

Then I took Ábris and left the hospital with him."

Belgian aid, pioneering foundation

A few days later, genetic testing confirmed that Ábris has type 1 SMA, which has a very short life expectancy. By then, Flora had already researched the disease on foreign websites and in scientific journals. This is how she found out about the first drug therapy, Spinraza. When she told the doctor on receiving the medical records that there was a drug therapy available for SMA, he was puzzled and told her that there was no drug for this disease. He advised Flora to take Ábris home and stay with him as long as she could.

"I'm not the despairing type, so I started contacting clinics abroad almost immediately. But I was not in the best financial position, and my relatives could not support me either, so I sold some of my more valuable and branded things. In the meantime, I set up the BJÁbris Foundation and started collecting money to cover the costs of the treatment. At the time, it was the first giant collection of its kind. Within a couple of weeks, a substantial amount of money came into our account."

After much negotiation, Flóra decided on a European drug trial program (not an experiment!), where the drug company gave the medicine for free and they had to pay for the hospital care. Most of the donation raised was used for this. Since Belgium gave them an appointment first, they travelled there for the treatment.

"We received the diagnosis in March and were in Belgium at the end of May. Ábris was ten months old then. Here we were referred to a world-renowned expert who gave me time to think after the first consultation.

He said that every child responds differently to the treatment: some do not improve, some stabilize, and there is a chance of progress, but he cannot say how much or how long the child will improve.

Nevertheless, I decided to go ahead with the program."

The treatment lasted three months, and fortunately, it was successful and Ábris started to improve. In the meantime, Flóra became more and more involved in the topic of SMA and, seeing the situation in Hungary, she decided to found the SMA Hungary Foundation (“SMA Magyarország Alapítvány”) in August 2017.

"With this foundation, my goal was to ensure that children with SMA have access to proper care in this country. I received a lot of research material from abroad, so I proposed the development of a new professional guideline for SMA patients, which was published in the Magyar Közlöny (“Hungarian Gazette”) in April 2018. In the meantime, the drug has been registered in Europe, so it is now available in Hungary, it is financed by the National Health Insurance Fund of Hungary (Hungarian acronym: NEAK).

Flóra, with the BJÁbris Foundation, introduced a non-invasive respiratory support device to the country, which was previously unknown to pulmonologists here. Since then, all SMA patients have received it free of charge. In addition, a cough machine has also been purchased from Italy and is now also provided on a subsidized basis. There was no small wheelchair available in this country either, but now it is also available with 80 percent state subsidy.

He’s in a wheelchair, but may eventually stand on his own two feet

Thanks to her work with the Foundation, Flóra has been involved in many events and has organized conferences in Hungary, too.

She came into contact with several pharmaceutical companies, one of which has offered her a position as a partner in charge of patient relations, which gives her some financial stability.

But Ábris needs constant medical aid, which they get mainly from Italy, and these, along with all sorts of other expenses, are a strain on the family budget.

"Until I had this stable job, I did all sorts of things for the extra income: I tapped beer at festivals, I was a hostess at wine tastings, but I'm not ashamed of that. I couldn't have taken a full-time job with Ábris in the early years, and I did the fundraising work for free as a volunteer. But I can do this work from home, which is a great help to me."

Thanks to four-monthly treatments, regular physical therapy, and home exercises, Ábris has improved and continues to improve to this day. Although he is in a wheelchair, he has every chance of getting back on his feet in time. He recently turned six and will start school this autumn. Flóra is hopeful that everything will go well, but her previous experiences at school do not bode well. She has long been looking for a school for her wheelchair-bound son.

"Since we have been abroad a lot, Ábris has learned English, so I looked for bilingual and English-language schools.

I didn't want to send him to a public school, because they only accept him with a document certifying that he has special educational needs. I didn't want to put that label on it.

Now we have an agreement with a British private school, I hope that there will be a teacher who will help Ábris to use the toilet because he can't do that on his own yet."

According to Flóra, there is a fear of children in wheelchairs everywhere, and in many cases, private schools are not accessible either. But she does not want Ábris to be homeschooled and sit at home. He's a very open and friendly child, and the community is important to him. But he is also a very lively boy, always smiling and with a great sense of humor.

"When I think back to where we started and where we got to, it's a world of difference. A couple of years ago I was a fresh graduate with a baby with SMA, and now I'm in a very exciting position at one of the world's leading pharmaceutical companies, where I can even shape the Hungarian healthcare system. I feel like our lives are moving in the right direction."