He can't hear the blows, they don't hurt him – Norbert Kalucza is the first Hungarian boxer to compete in the Olympics as a deaf person

As a child, he couldn't hear or speak, but he wanted to prove that he is as good as anyone. Roma and deaf-mute, he ended up in a boxing gym at the age of seven, and through sheer willpower, he learned to communicate with words. In the ring, he could read his coach's lips and his opponent's and referee's movements, and he made his dream come true when he became the first Hungarian deaf person to box at the Olympics - in Beijing in 2008. With more than 300 victories, he now trains children and adults and is working on founding a sports association for people with disabilities. During the interview, Norbert Kalucza pronounces words slowly but clearly and understands the questions, only occasionally assisted by his wife Vivien. They have wonderfully complemented each other for twenty years and have two children together.

What are your memories, what kind of difficulties did you have to face as a child because you were deaf?

Because I didn't have hearing aids until I was eleven, I missed out on a lot of what was going on around me. When I had to read at school, I tried, but I could see people laughing at me. I cried and stopped reading, and then the teacher felt sorry for me and started to practice speaking with me separately. It was a special school for disabled children.

What was your family like?

There were seven of us brothers and sisters - two girls, five boys - and all but one of my brothers was born with some kind of disability. Most of us are hearing impaired, although our parents were not. I remember they watched TV at home and because we didn't understand what was going on, we laughed when they did. I started to develop my communication skills when I was seven years old and went down to the boxing gym. Everyone there, including coaches, and teammates were constantly talking to me, I had to keep in touch with them somehow.

Where did the idea of boxing come from at such an early age?

I saw this as an opportunity to keep myself busy and show the world who I am, and what I can do. I was very motivated by the old Bruce Lee and Jean-Claude Van Damme films, they were my role models. I wanted to be like them and the coaches saw my talent, but first I didn’t get medical permission in Debrecen to go to competitions, only later in Budapest.

How were you able to keep up with the others, who obviously had an advantage over you?

I copied their movements, and the coach showed me what to do. I felt like I was doing well.

So much so that you might have suspected that later you would grow up to be an athlete.

I knew exactly what I wanted to be. And the fact that I can't hear has an advantage: I can't hear the cheering fans, for example, so I'm not distracted by any noise.

I have to take off my hearing aid in the ring, where I can only read my coach's lips. At the end of the round, I don't even hear the bell, I just feel the opponent starting to move away and the referee is closing in, that's how I know there's a break coming and I stop punching.

In the footsteps of a famous Italian predecessor

In sports encyclopedias, we have to "turn the pages back" almost a century to find a story similar to that of Norbert Kalucza. At the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam, Italian boxer Carlo Orlandi won a gold medal as a deaf lightweight, and Norbert was the only Hungarian to follow a similar path to his.

It is inevitable that if one sense is weak or damaged, the others will be stronger...

This is also true for me, my imagination is especially strong. I can imagine how everything will happen - in the ring too. I can anticipate whether I can do the job or not, and I know if I'm going to lose. I've fought over 360 fights and I've only lost ten percent of them, 39. I was a national athlete for twenty years, competing at 51, 54, and 57 kilos, and I never said no to any invitation.

Were you a good competitor type?

Everyone is nervous, but if you're not afraid, the blows don't hurt. I always imagined that my opponent would be as nervous as I was, and I used my imagination to prepare. I was good at sprints and long-distance running, which I achieved by always imagining that I was running in front of a train and that if I stopped, it would hit me. I would run in front of the train for 60 minutes, never stopping before the finish line. And in the sauna after training, I imagined the door was closed for 15 minutes and I could only get out after that.

Did your opponents know about your hearing loss?

No, because I always went to the pre-game weighing without my hearing aids, so I guess they thought I couldn’t understand their language.

Have you ever been mistreated as an adult because you can't hear?

I have been taken advantage of several times without my knowledge because I am not able to pay attention to everything. When I signed to be a professional in the Czech Republic, I found out only later from my manager that my coach was supposed to pass on my share of the match money, but he kept it for himself.

In the ring, however, no one could fool me, it was the performance that counted, so I had a lot of happy moments there.

You want other special needs athletes to experience this kind of happiness, this is the reason why you would like to start a special association - in addition to your present job of coaching boys, girls, children, and adults.

I know exactly what someone born with a similar disability has to face in everyday life. I would offer them a sports activity in my association, where anyone with a disability or coming from a deprived background could come to train. I would also like to make their dreams come true. I always say that if someone wants to try a sport, it's no excuse for not hearing anything, you have to do it, and there is a solution! I will also give a presentation in schools to make more people aware of the opportunity. I'm also looking for children who can become athletes as adults, but also adults who don't want to compete, just learn self-defense, lose weight, get in shape, and relieve stress. I know it is twice as hard to succeed in sports with a physical handicap, but it is not impossible. I will see who is capable, and what can they can achieve with the talents they have, and with patience, I’ll help the achieve it.

Vivien about their plans

"There are already people interested in the initiative, who have a sick child and their psychologist suggested that they take them to do some sports. Norbi has the experience and talent to know how to help such young people through boxing to make progress and give them self-confidence. He would put together a good team, who would improve their communication skills as well as their physical strength. Just as Norbi has improved a lot through sport, everyone deserves a chance. The idea could be realized in Debrecen, we are organizing the details and looking for sponsors. We're planning everything in advance so we can start as soon as possible."

Norbi, I have never heard you talk about your Roma origin, but the more people - like other Roma young people - know this about you, the more you can be a role model for...

The bottom line is that I give respect to everyone who comes across me, no matter if they are Roma or non-Roma, no matter what their background. Sport teaches me that. Anyone who speaks badly to me, I leave immediately without saying anything back. That's why we have the police, the security people, or in the old days, the teachers at school, to take action. As a kid, many people thought I didn't understand what they were saying, so they would tease me behind my back, but even then I didn't make a scene then and there. I stood up for myself by telling it to the right person. I developed this kind of defense myself, I learned everything by myself.

And I also know that there are many talented Roma, whether in sports or music, but most of them give up quickly and drop out.

What else do you like to do besides sports?

Dancing. Either at home or in the gym. If someone cancels a training session, I use the time for that. As a training distraction, my students, the kids, really enjoy it. Just like I used to imitate Van Damme's moves, I also learned to dance from TV: folk, hip hop, everything. I don't even need sound, I can feel the beat.

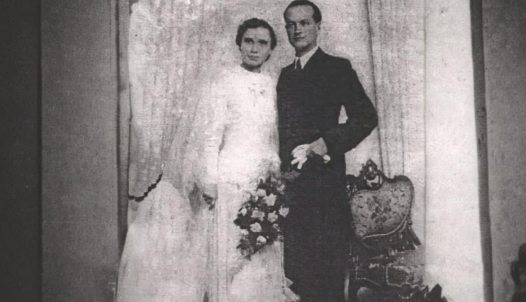

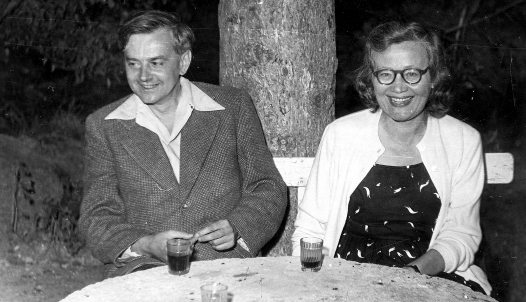

How long have you and Vivien been a couple?

It will be twenty years this summer. We got married a couple of years ago, but that's just a piece of paper because we've been together since we met. I owe a lot to her, she helps me a lot to practice my speech: which words mean what, what not to say, how to say hello, how to talk... And I pay attention to her. It happened that she didn't even say anything, but I could tell she was hungry so I brought her a burger.

Vivien about their relationship

"Norbi has never been a talker, but you could always tell what a sensitive, pure-hearted, smiling, lovable guy he was. His goal in life is to show that he can be complete despite his disability. When we first went to the cinema, he didn't understand the film, but he was ashamed of it. In the end, I could feel his embarrassment, he smiled and I asked him if he understood any of it. He said not really, but he was afraid I would laugh at him. Then his eyes lit up when I explained the story to him instead. Later, I found out what a family man he is, he helps me a lot with everything, including house chores. I look up to him because in 20 years I have never once been disappointed."

Norbi, how does it feel to be a father?

Wonderful! Our daughter Vivien Pálma is 14 and our son Norbert is three. He is very fond of his father, spends a lot of time with me at the gym, loves to hit the bag, and seems to be as active as I am.

You must be proud, just as your parents must be proud of all you have achieved.

Unfortunately, my mother is no longer alive, but she was very proud of me. All the more because she knew how much sacrifice it took to succeed. When they moved to Sátoraljaújhely, I was still a child, and my mother asked me to go with them. I said no because I wanted to stay in Debrecen in a dormitory, which Sándor Szabó, the president of DVSC, helped me to get.

Crying, my mother was begging me to go, but I said no, I had set my life on boxing, and I wanted to go to the Olympics. She understood.

I promised to come home on weekends, but due to competitions and training camps, I rarely did. This was a sacrifice, as was the fact that when friends invited me to their birthday parties, I was there, but even though I had food and drinks on the table, I didn't eat or drink in preparation for the weigh-in. In fact, I went out just to dance off the extra pounds.

Looking back on your achievements, what are you most proud of?

I have eighty-seven international trophies at home, but I'm most proud of the European qualifying tournament when I won the quota for the Beijing Olympics. It was not an easy draw, though, and I won the gold medal against the toughest opponents. There are very few deaf athletes in the world who have ever qualified for the Olympics, and I am one of them. Wherever I go, people look up to me, respect me, say hello, or hug me. I started doing sports to achieve that.