”Someone from above writes into my script” – Oscar-winner Ferenc Rófusz sent a message with The Fly: we'll get hit on if we buzz too much

Ferenc Rófusz, the animation filmmaker and creator of the first Oscar-winning Hungarian animation film (The Fly, 1981), recently received the Lifetime Achievement Award at the CineFest Miskolc International Film Festival. We were honoured to have the opportunity to hear the director talk in detail about the special twists and turns of his career and the milestones of his work across continents after the award ceremony.

Is it true that your family has a special bond with Cardinal Péter Erdő?

My mother was the nanny of Péter Erdő for two years, and as luck should have it: when she grew old and she was in the retirement home of the Order of Malta, they met again. At a celebration in the small chapel of the home, the Cardinal celebrated Mass, and the two of them reminisced about old times.

Did your mother play an important role in your decision to start drawing?

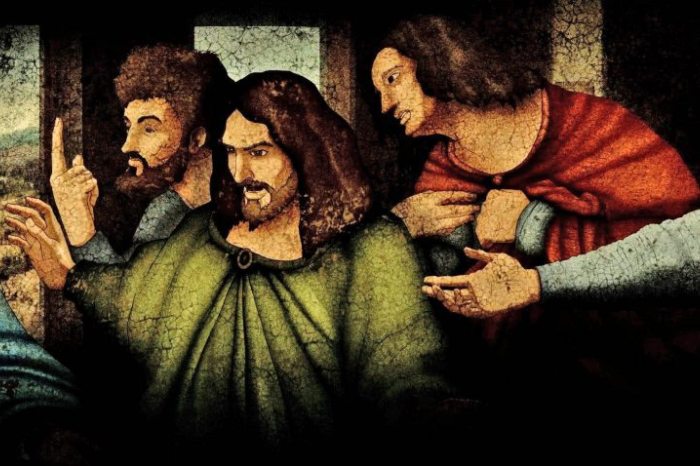

She always supported my ideas, she said that if I believed in something, it would come true sooner or later. This is true for my film The Last Supper, which I had to wait 40 years to make because I had submitted the project in 1978, but it was rejected because of the religious theme. In hindsight, I think it's better, because if I had been able to make it then, we would have had a much lower quality production with the technology of the time. Now, however, we have lived up to Leonardo's painting a little. I know from this that if something doesn't work, you shouldn't press it, because no matter what I dream up, Someone from above will write into my script anyway...

In your script, which included filmmaking as well as drawing from a very early age?

There were four of us brothers. We played sports, as there was no television or computer at that time, and we didn't sit isolated, glued to our phones either. My mother drew beautifully, she dyed scarves, she designed patterns on silk shawls, and she tie-dyed. She taught me too, because she saw my talent, paying for summer art camps, and drawing lessons. Animation wasn’t taught at any school back then yet, so through a friend I got into the Hungarian Film studio, Mafilm’s animation group, and set designers. Then in 1968, I was able to apply to the Pannonia Film Studio, where sixty of us applied, six were accepted and I got in. I started with the Gusztáv series, besides which we had other productions such as the Mézga Family and Dr. Bubo.

The internal animation academy allowed us to learn from the bests: Marcell Jankovics, József Nepp, Attila Dargay, and József Gémes. Since then, I have been to many studios all over the world, but I have never met so many talented creators with so many different styles!

You had to spend at least ten years in the field to be allowed to submit your own film project, and for me, the first one was The Stone (“A Kő”). I remember József Nepp pulling out his drawer and saying, here are 15-20 scripts, choose one. And I wanted to draw the whole world in those three minutes!

In the end, you amazed the world with your 1980 background animated piece "The Fly". Do I know correctly that it was inspired by a Pink Floyd song?

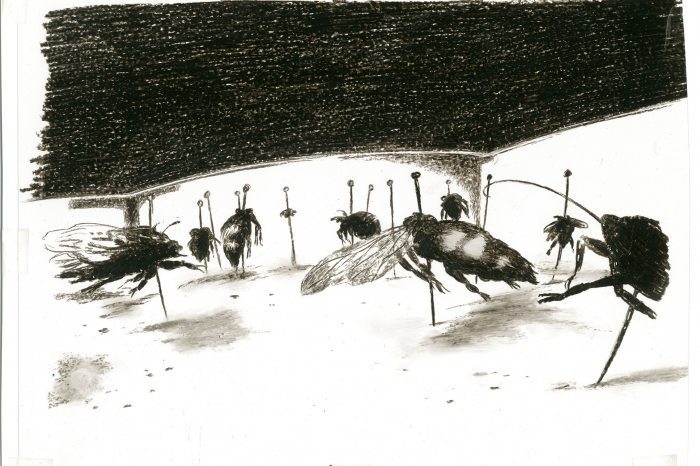

My colleagues and I were very much centered around music, and I was a big Pink Floyd fan, I felt it very fulfilling at the time. They were the first band in the world to use noises for their songs, adding effects to them that made the genre new. I was inspired by a song from their album Ummagumma, in which a fly flies into a building and they chase it. The film flashed before my eyes immediately. Until then, all animations were made with characters jumping around in front of the background, playing the story for us. I wanted to come up with something new, because our masters had already done everything, and there was no way to top that. I had the idea of putting the camera in the eye of the fly so that we couldn't see the fly or the person chasing it, just the background. This was done by drawing a picture, but as the camera moved away, everything had to be drawn again, so we made over 3,600 drawings. Two ladies and I worked on it for two years.

Watching the film, I wonder a bit how it passed the socialist censorship back then...

It was very fortunate that Elemér Hankiss upported me all the way in Pannonia Film Studio, because it's true: questions came from above about who was the fly and who was the chaser. It wasn't like today, where you put forward an idea and no questions are asked. But it involved the feeling that we didn’t stand a chance and we’d get hit on if we buzzed too much.

It was indeed a miracle that the film was finally approved, but within a good six months, it won every festival and was in the top three at the Oscar nominations.

And at that time, in addition to professional innovations, they also paid special attention to the message that the competitors from Eastrealizeope were bringing.

When did you start to realise that your idea of background animation was a big one on a global scale?

We were invited to the Ottawa festival, we went there, and I had never seen a screen the size of that in my life! The Corvin and Alfa cinema’s screen in Budapest were the biggest I had seen before that. The people whose films were screened that day sat in the front row, the filmmaker stood up at the end and the audience applauded or expressed their displeasure. When my film started, there was a mad roar, a booing, we were convinced we had failed. I didn't know at the time that this was a sign of approval among young people in Canada. At the end of the film, I stood up, the lights came on me and an older gentleman about six feet tall stood up next to me. He put his arm around me and congratulated me, saying that it was fantastic! It was Bill Littlejohn, the legendary animator from Walt Disney, whose film was screened after ours, and he knew right away, what I didn't, that I had made a huge professional innovation. He inv,ited me to Los Angeles, drove me around the city and showed me everything.

But you could not go and receive the Oscar Award in person...

Because comrade Dósai from Hungarofilm went there instead of me and was handed the award, although I was of course invited to the event, but didn't get a passport. The reason given was that I had no chance against the two Canadian candidates. But a delegation of several people went, and the next morning at eight o'clock I heard on Radio Free Europe that 'The Fly' had won an Oscar. It was shocking!

Of course, it would have been quite different to be able to sit there when the envelope was ripped open, it wasn't easy to process that instead of all that I was at home lying in bed and waking up hardly believing my ears.

The Hungarian Radio announced it only in the afternoon, and I was allowed to go out two months later to collect the statue, which was taken back from Comrade Dósai later that evening. Because Littlejohn had told them that he knew me, and I couldn't have changed that much in six months, so someone else went out on stage on my behalf. Of course, this immediately became a story in the media there. If I said to a young person today, you've been nominated, but I'll bring the award home, I think they wouldn’t hide their opinion…

How much has the Oscar Award changed your life?

When I went to collect the statue later, I was confronted with how business works out there. Littlejohn hosted me in fantastic conditions, and his first question was what I had in my suitcase. I said, well what should I? A tennis racket, because we were both tennis freaks. He asked me where the original drawings were. I said, well that would have been quite a load, I couldn't even lift it, how could I have taken them? He said, "You could have signed them at a gallery on Sunset Boulevard, and if we sold each one for $50, you'd have the money for your next movie!” But they also wanted me to do commercials, saying my name would sell to 15 countries as an Oscar winner. I realised that the Oscar Award didn't bring in money directly, but it brought opportunity: it opened doors and could multiply my salary.

In the 1980s, you left Hungary not for the USA, but first for Germany and then Canada. Why?

On the one hand, President Reagan tightened the rules, and people from Eastern Europe were not given a green card, and I couldn't risk it without one. On the other hand, I had a plan at home, a feature film called The Rabbi's Cat (“A rabbi macskája”). However, the script was rejected, as was Erich Kästner's The 35th of May, which we also submitted. So I went out to Germany under a contract with the Concert Office as an artist of intellectual products, with a work permit. After three and a half years, I accepted an invitation to Canada to work for Nelvana, the biggest animation studio there. They worked with today's 3D tecrealized which I regretted at first, but then I realised it was the future.

After two years I started my own studio and worked everywhere from Toronto to Chicago and Los Angeles. Then in 2000 I came home by accident.

By accident?

My marriage broke up after 30 years because my wife never felt at home there and returned to Hungary, but the opportunity for professional development kept me there. I returned home because of my current wife, Zsófia, who is a ceramicist, and founded the Buda Drawing School with two of her former classmates. I would recommend to all young people to go abroatheirr a couple of years and then return and put your knowledge to good use. I have my roots here, as a lawyer friend of mine in Canada said: I will never be a Canadian because it wasn’t there I went to school or met my first girlfriend, I didn't get caught by the police there and it wasn’t there I got drunk for the first time in my life. At home, I picked up where I left off, and my colleagues and I understand each other and finish each other’s sentences. Unfortunately, I am limited physically by an illness, but I can sit and draw at my desk, my hands and brain work.

Is what you have achieved as much appreciated now at home as it was appreciated abroad?

Hungarians used to have a kind of envy, they were very quick to judge. When I left, many of them thought I was a traitor, and it never occurred to them that I wasn't doing it for the money. Today, this attitude has changed, as can be seen from the fact that I have been awarded the title of Artist of the Nation, the Order of St. Stephen or the recent CineFest Lifetime Achievement Award. Of course, you get frightened of age when you receive a lifetime achievement award, but it is still a joy because it is given by the profession.

I managed to leave something behind, which is the goal of every artist, and this feedback is very good doping at the age of 76.

Do you think if we watch your films we will get to know your personality?

It's a good question. I go to high schools to give career advice, and there the students are uninhibited in saying what they think. The other day, one of them stood up and said, with due respect, they'd seen my films, and although I seem to be a humorous, cheerful person in real life, how come in all my films the main character dies... And everyone fell silent, including me. Oh my God, I thought, how right he is! It seems that what's hidden deep inside you comes out somehow. I made the "Ticket", also a background animation film, in 2011 at the urging of my eldest son. It's about how everyone gets a ticket for life, not knowing how many stops, what class of train, or when to get off. The film spins through a lifetime, and at the end the protagonist is buried, of course. And in this film, I had drawn the walker, the IV and the wheelchair, even though I could still play tennis for six hours at that time. I drew my own future, because now, as long as I live, I have to go to St John's Hospital every five weeks for an infusion to slow the deterioration in my mobility. Am I right in thinking that Someone from above keeps writing into my scripts?

What you say is thought-provoking, as are your films. Why is it important for you to make an animated adaptation of Hieronymus Bosch's triptych "The Garden of Earthly Delights"?

Because I feel it's very current, even though Bosch painted it 500 years ago, when Leonardo's mural "The Last Supper" was painted.

Today, people are morally bankrupt, they should be shaken up and confronted with this. I would show my vision of this work of art, by bringing the 21st century into it.

Last year we made a two-minute trailer of "The Hell" panel, in which we brought in airplanes with sound effects, even though there was no war yet at that time (visitors to the Bosch exhibition in the Museum of Fine Arts could see this - ed.) But we can also be modern just by using a flash because 500 years ago there was no flash either. This animation is at least a year and a half or two years' work for five or six people, and as time is passing, it could be my last challenge, I want to make it permanent. There is also an idea for this and for The Last Supper, that wherever the painting will be exhibited, this animation film would be projected in the lobby, translated into five languages, so that people could go in and see Leonardo's work, or Bosch's after they’ve seen the animation of them. They would surely leave with an even deeper understanding, even maybe taking the film with them on a USB stick. Because Leonardo once had to say what he wanted to say in a single image, whereas we have 11 minutes to do so.