”Professional musicians need nerves of steel and the physical condition of an astronaut” – There might be a lot of pain behind musical achievements

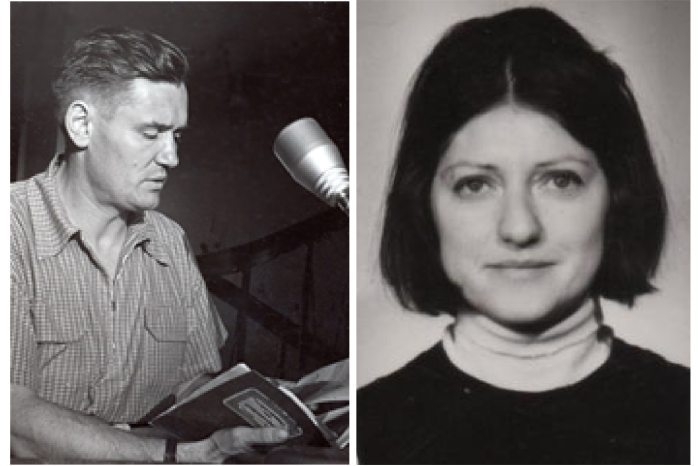

As early as 1959, Zoltán Kodály noticed that there were many health problems among musicians: tendonitis, tennis elbow, golfer’s elbow, spinal disorders, and, in other words, serious illnesses that developed from playing instruments and overuse. At his suggestion, the management of the Hungarian Academy of Music asked Dr. Géza Kovács to take care of the health and stamina of musicians, which is why he is also known as the saviour of musicians. His student, fellow researcher, and co-author, Dr. Zsuzsanna Pásztor, discusses the so-called ‘Kovács method’. She was recently awarded the prestigious Knight's Cross of the Hungarian Order of Merit, civil division, for her efforts in preserving the working capacity of musicians.

Were there any similar efforts to protect the health of musicians before Kodály? Clara Schumann, for example, wrote in her diary notes that her father, who was also her piano teacher, advised her to spend as much time walking outdoors as she spent practising, to strengthen her nerves.

Yes, and what a broad-minded advice this is! Of course, a young musician who practices for six hours today cannot spend six hours walking in the woods... I miss that. Musicians who have studied in Russia tell me that a teacher who is supervising keeps walking past the practice rooms, and knocks on the door of the room in which the instrument stops playing because the work cannot stop. Those who can endure this will go on to win prestigious competitions - if they can.

It is a destructive approach, where it is not talent that counts, but stamina, and which makes breakdown inevitable.

For example, Leon Fleisher, the famous American pianist, developed a neurological disease at a young age that caused his right hand to go into spasm. He was forced to switch to left-handed playing and continued his career as a conductor and teacher. It was only thirty-five years later that he managed to return to the concert stage and played with both hands. Eckart Altenmüller, physician and musician professor in Hanover, believes that the main cause of this serious musical illness is perfectionism, where ambition is greater than strength.

When I'm sitting in the concert hall, listening to the music flowing, I have no idea that musicians often have to go through a lot of pain to play in the orchestra... Can there be pain, feelings of deprivation, even severe burnout behind the performance?

I developed a hand injury in music high school that made me miss three months of practice. No one could help me because we don't have any kind of special medical help or therapy for musicians. Our doctors do not learn about occupational injuries associated with musicians. The aching hand needs to rest, so they put it in a cast, but when they take the cast off and the musician starts practicing, the condition relapses. The immobility causes the tissues to weaken and become even more vulnerable. The surgeon will operate on the inflamed lump in the tendon sheath, but the structure in that area will become weaker and the strain will reappear when it is used again.

As a music academy teacher, Kodály saw many of his great colleagues and students fall ill and drop out of the profession. The master urged the Academy's leaders to find some kind of help. At that time, there was no physical education or swimming lessons for musicians – that, of course, made us, the students, delighted. Everybody hated PE, and we dreaded even the thought of a vault or a speeding basketball. The physical education of musicians is not always the best these days either. Recently, one music high school had a hand fracture every week. Kodály, who was a regular sportsman, once explained what the physical education of musicians should be like. Something that refreshes, relaxes, revitalizes physically and mentally, and counterbalances the great nervous-physical strain. It was at Kodály's initiative that the management of the Academy of Music asked Dr. Géza Kovács, a scientific researcher in physical education, to attend to the musicians' complaints.

Is it possible to physically measure the load on musicians?

It can be compared to a person doing hard physical work. Kodály once commented on this, saying that the work of a musician, expressed in metric kilograms, beats the performance of a heavy physical worker. I myself once tried to measure roughly the power required to play a heavy chord on the piano, such as in one of Chopin's études. I saw a scale at the post office, and put my hand on it and pressed on it as if I were playing this Chopin on the piano. The pointer jumped to 15 kilograms.

This Chopin etude is full of such chords for six pages, which led me to conclude that a practicing pianist moves tons in an afternoon.

If someone's hands are not trained enough, they will inevitably suffer an injury. If a musician is not mentally able to cope with the strain, there are also subjective symptoms and signs, losing the will to work, and becoming dull and grey.

Grey?

Yes, the musical production becomes grey, and boring, the heart and soul are gone, and the playing that used to be so exciting fades away. Fatigue overrides even the most beautiful musical ideas.

I mean, you don't think of musicians as people who have just come from the gym. They are fragile, sensitive people whose physical bodies are more a contour of their souls...

The image of the pale, thin, sensitive artist is more the romantic ideal of the 19th century. I, on the other hand, teach my music academy students that they need to have the physical condition of an astronaut and nerves of steel. Our children today work under tremendous pressure, they need to be strong and have an endurable working capacity. Now we have our wonderful Kovács method, but still, musicians have a lot of problems. Our survey last year with 15-20-year-old students showed that eight out of ten children were already struggling with some kind of injuries, and one child had three to five different symptoms. It is not only problems with playing instruments, not only hand pain or disorders of the facial muscles of wind players and the vocal cords of singers, but also serious neurological disorders such as depression, panic attacks, anxiety, and even suicidal tendencies are common. Youth is the golden age of human life, a time of hope and happiness, and even then it can bring so much pain and suffering!

It takes around 16 years for a musician to become a stage-ready performer or a qualified teacher. By the time they reach this stage, they are already suffering from serious health problems if they don't get help.

How did Dr Géza Kovács approach the task?

He gave exercise classes and counselling. The exercise classes started very interestingly. Due to the lack of suitable rooms, the classes were held in the Small Hall of the Music Academy, now Solti Hall, where there was hardly any free space, and the music students had to work out between the rows of chairs. The professor worked with each one of them individually, telling them how to practice, how to organize their work and rest, how to use hot and cold water, advised them to go outside often to get some fresh air, and also talked about nutrition. Everyone who went to see him got well.

How did this become music pedagogy?

I was one of his clients being the sickest student at the Academy of Music. After I recovered with the help of Professor Kovács, I thought that if this method worked for me, it would work for my students, too. Initially, I just wanted to use some of the elements of the movement program as a relaxation before music lessons for the children who were tired after school. We played with balloons and balls for a few minutes each class. After about four months, something happened that I hadn't expected. Even the most clumsy child developed a dexterity in his hands. It was a miracle, because the initial stage of learning to play an instrument is usually a very difficult one, and it takes a long time to get the instrument to sound nicely in the hands of little children. But this method speeds up the process considerably.

It's a kind of "musical brain surgery" that transforms the nervous system: it builds into the brain programmes that lay the foundations for musical skills.

Did you have to endure any problems, offences?

Oh, yes. There were plenty of difficulties with the superiors and with the authorities. At first, parents complained, saying that they were not paying for their children to play ball in music class. My director, bless his memory, who supported my experimental work, provided a courtyard classroom with no view from the outside. It was a tough struggle, sometimes the experimental program became a real 'secret curriculum'. Today it is an accepted university subject, under the name of Music Movement Development.

I have seen a photograph of Dr. Géza Kovács participating in an autopsy with his students.

Dr. Miklós Réthelyi, Professor of Anatomy, former Rector of the Medical University (former Minister), was a participant in our movement classes for many years. At our request, he regularly gave us autopsy demonstrations. These demonstrations were part of our theoretical education. The Kovács Method teacher trainees still receive solid anatomical training today.

Can the Kovács method help with stage fright?

Of course it can! Warming up before a performance can have a magical effect on the nervous musician. Of course, let's not imagine the musicians jumping up and down in their formal dresses! This gentle warm-up calms down the mad adrenaline rush that shakes the musician's whole body before a performance. The movement acts as a kind of beneficial oxygen spray, normalizing hormone- and nerve control.

During the gentle warm-up movements, the character simply forgets to be nervous.

The dreadful vegetative symptoms of stage fright, the tremors, the pounding heartbeat, the anxiety, the visceral complaints disappear, leaving nothing but eager excitement and focused attention.

Dr Géza Kovács was famous not only for his methods but also for his charismatic personality and radiance.

He was a loving, reassuring, and motivating person. He was characterized by thoughtfulness, gentleness, empathy, and infinite modesty. He often stressed that he had only established his method and would not have time to develop it. Indeed, he laid the foundations, I put up the walls, and then my students will put the roof on the building. Let this method be a treasure for everyone, let it be introduced into mainstream education! This is no longer a dream. The Kovács method has been included in the training of special needs teachers since 2007. Teachers use it effectively in the education of children with atypical development.

I saw a skipping rope, and a colourful balloon in the pictures, and I even felt like going in for a lesson.

Games, laughter, balloons - these also help you recover physically and mentally. The relaxing balloon game is undoubtedly one of the most attractive elements of the Kovács Method training program. But in addition to them, there are tens of thousands of strengthening, relaxing, stretching and dexterity-building movements., that make up the whole repertoire.

I can't resist asking: didn't you fall a little in love with Professor Kovács?

Of course, I did, and I was not the only one. He had such an attractive personality that he charmed everyone, but he was a family man, a family-loving man, a stable personality, and extremely fair to everyone, so we admired him from afar. He had morals and infinite integrity. That's why people took his advice. I was a very weak student in fragile health, so my piano teacher József Gát sent me to him. However, there was no way I wanted to go to the 'Kovács lessons', because I had terrible experiences of gymnastics lessons in high school. But I finally convinced myself to go to the Small Hall of the Music Academy, where he was teaching.

I watched, fascinated, as the colourful balloons floated towards the ceiling like planets in a planetarium.

It's not a PE class, it's a miracle, I said to myself, and I felt I would be stuck with it for life.

Dr. Zsuzsanna Pásztor was born on 14 June 1935 in Szeged. She spent her childhood in Szentes, where she started to study music. She completed her high school studies in Budapest, at the Béla Bartók Conservatory, and graduated from the Academy of Music in 1960 with a degree in piano pedagogy. She is a lecturer at the Department of Teacher Training at the Liszt Academy of Music and at the Institute of Art Mediation and Music at the Faculty of Humanities of the Eötvös Loránd University. For her high quality work she has been awarded the János Apáczai Csere Prize, the Príma Prize and the Knight's Cross of the Hungarian Order of Merit, civil division.