”At the moment of Jesus' birth, the Lake Balaton came to be” – the magic of Christmases past

There were many Christmas customs and traditions in 19th-century Hungary, which are still kept by many families today. What are they? How did young and old celebrate Christmas in castles, in homes in Pest-Buda, or in rural villages? What were the beliefs and superstitions, what kind of food was put on the table at Christmas, and what did people decorate their hearts and homes with?

In different centuries and different countries, Christmas has been celebrated with different traditions, and in our country, too, many different customs have coexisted. Christmas was celebrated differently in the capital and differently in the villages of different parts of the country.

They cleaned up, they reconciled

For the fasting of Christmas, on 24 December, people in villages carefully cleaned their houses and porches, even the stables of their cattle, as they awaited the most important guest in their homes: the baby who was about to be born. They also wanted to welcome the New Year clean and tidy, so they washed the furniture, put fresh straw in the bed, took a bath, and washed their hair. In many places, washing was accompanied by superstitions and beliefs. It was believed that on Christmas night (less often on New Year's Eve, New Year's Day, or Epiphany), water drawn from a well or river was golden water, good luck water, and that if you drank or washed in it, you would not get sick. It was also often given to animals to keep them strong and healthy.

Christmas was a time for fasting and for this reason, families tried to make not only their homes and bodies festive but also their hearts.

For the holiday, they tried to reconcile with whoever they held a grudge against and sent gifts to poorer relatives, and the family's regular workers.

Honey, walnut, and apple

In some villages, the most characteristic preparations for the holiday included covering the living room and the Christmas table with straw, and in other places, wheat, straw, and fodder were put in a basket under the table. The straw symbolized the stable in Bethlehem so that there would be room for the incoming Jesus, his parents, and their donkeys.

Christians prepared for every great feast, including Christmas, with a physical and spiritual cleansing, which included fasting. So on the 24th, the fasting day of Christmas, they ate no meat all day, and the meal was a simple one, beginning in many places with honey or garlic dipped in honey, to ward off evil and make the New Year sweet. In some regions, they also ate wafers flavored with honey, or racked walnuts, and those who had a nice, healthy nut in the shell had nothing to fear of any diseases in the coming year. Apples were an even more typical dish than walnuts on the Christmas menu, and their consumption was also associated with a wide variety of customs and beliefs. In Bátya, for example, the farmer would cut a beautiful red apple into as many pieces as there were people in the family so that the apple's power would keep them together in heaven. Pasta with poppy seed, poppy seed dough, and scones were common dishes.

When the water in the stream turned into wine...

In many families, Christmas Eve is an intimate evening with a festive dinner, when all the expectations of Advent are fulfilled, and it was no different a hundred or two hundred years ago. Families stayed up late, often playing cards after dinner, but the winner’s prize was not money but nuts. At midnight they went to mass, to which folklore also attached superstitions.

It was believed that at this time the newborn Jesus cast out the powers of darkness, the heavens would open, miracles would happen, such as the future being revealed, young people would know who their future spouse would be, and animals would speak in human tongue.

The water in the stream turns to wine, and the river flows with milk and honey. In his book, Christmas, Easter, Pentecost, Sándor Bálint mentions an old German record from 1848, according to which the Lake Balaton came to be at the moment of Jesus' birth, "to the awe of all, as the people living there still tell us today".

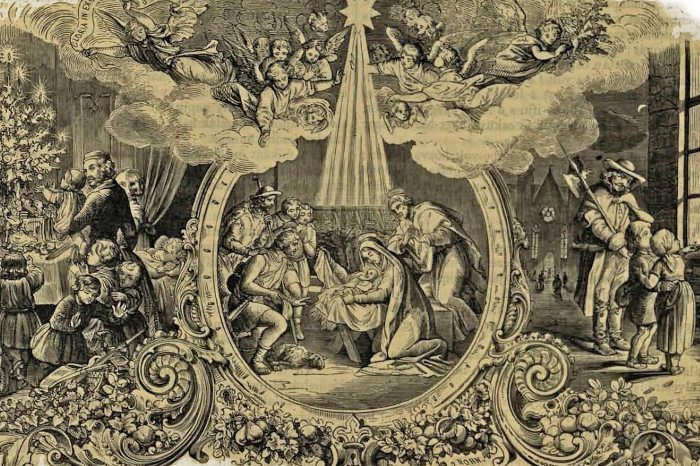

First Christmas trees

In Hungary, Christmas trees probably became popular in the 1820s among the nobility first. Countess Teréz Brunszvik, who founded Hungary’s first nursery, the “Angel Garden” in Buda, celebrated the birth of Jesus with the kids in her care beside the first Christmas tree in 1828. Toys and useful gifts were hung on the tree as decorations, which the Countess then distributed to the children of clerks, tradesmen, carters, and laundresses. Archduke Joseph's third wife, Mária Dorottya, also decorated a pine tree in the family’s palace, and Hungarian politician Baron Frigyes Podmaniczky also claimed that he remembered his mother putting up one of the first Christmas trees in Hungary.

In the 19th century, Christmas on noble estates was not an intimate, small circle event, but was complex and ceremonial, where the family celebrated with the servants and the estate workers. In the Podmaniczky family manor house in Aszód, the servants would gather at 5 pm and the head of the family would present each of them with a gift, accompanied by a few affectionate words.

At six o'clock, the door to the head of the family's living room opened at the sound of three bells, and his five children were able to receive their presents. Each of them also got their own Christmas tree, which stood on a large table.

In the 1830s and '40s, decorating a Christmas tree became more widespread, and Christmas trees appeared in civic families’ homes, but in the countryside, it was not until later, at the end of the century or the beginning of the 20th century when they started decorating Christmas trees. At that time, evergreens were decorated with handicraft ornaments, sweets, apples, and nuts.

In 1864, Count Gyula Andrássy, who later became Prime Minister of Hungary, was celebrating New Year with his family at their estate in Tőketerebes (Trebiŝov, Slovakia), and decorated a huge black pine tree with paper roses, burning candles, gilded apples and walnuts. On Christmas Eve, they gave presents to the family, and on Christmas Day they celebrated with the estate workers and their children in the castle around the Christmas tree. Gyula Andrássy's wife Katinka presented the gifts, many of which she had made herself.

Royal Christmases

Queen Elisabeth and Emperor Franz Joseph often spent Christmas in Hungary with their children, often in Gödöllő. Queen Elisabeth was born on 24 December, so she celebrated her birthday on the same day. A mass was held in the morning in the chapel of the castle, and in the afternoon they too had a Christmas tree and gave gifts. Elizabeth had several Christmas trees put up for the servants, staff, and their children and one for her own family. The pine trees were decorated with sweets from the court confectioner, Henrik Kugler, including coloured wax candles, ribbons, and roses, and the presents were placed on a table with a white tablecloth. After the presents were given, they played games, Mária Valéria, for example, loved to play blindfolds. A special Christmas tree was also set up for the children of Gödöllő, under which the students and the little ones could receive lots of sweets, new clothes, school equipment, and toys.

Mária Valéria made gifts for her loved ones herself, and one Christmas she made a coloured map of Hungary for her mother. She also greeted her on her birthday, always in Hungarian.

The holiday was not just about giving gifts. Mária Valéria was also called the Hungarian Princess, because her mother spoke only Hungarian to her from an early age and they spent a lot of time in Hungary. Her teacher was Bishop Jácint Rónay, who also recorded several Christmases. On one occasion, at six o'clock in the evening, they stood around a picture of the birth of Jesus, which had arrived from Vienna, and sang Christmas carols with the court, accompanied by Mária Valéria on the piano. The only light in the room was a small lamp behind the transparent picture, so it was only later that they noticed that the royal couple had entered. The carolers went silent with surprise, but the royal couple encouraged them to continue singing. On a later Christmas, the Bishop recalled, "we celebrated the anniversary of the birth of Her Majesty without a sound. At eleven o'clock I celebrated a silent mass for Their Majesties and the Archduchess. At six o'clock in the evening, in the hall of Her Majesty, a forest of burning candles and tiny flags fluttered on the giant Christmas tree, the branches of which, as if in homage, bowed low under the weight of the beautiful bonbons..."

How the capital celebrated

During Christmas, Pest-Buda was a hive of activity. Shop windows were decorated, and tents selling gifts were set up on the banks of the Danube: gilded nuts, small toy musical organized, sugar dolls, lambs, and ornate sewing boxes. The women organised Christmas charity fairs and performances to raise money for the needy. Dóra Kovács, a tourist guide, writes in her book that at that time the heart of Pest was beating around the Parish Church in the city centre. The Church Square opened up into the Town Hall Square, where hundreds of pine trees were sold in the winter between stalls at the city's largest and busiest market.

Once when the Danube froze over, the pine fair was held on the ice scattered with sawdust.

Váci Street and Lipót Street were also bustling with shoppers. From the merchants you could buy Santa Clauses, ‘Krampuses’ (little devil-like figures accompanying Santa), wooden dolls, fruit cakes, dried pears, Greek raisins, almonds, oranges, pictures of various Saints, and bouquets of rosemary. In the last third of the 19th century, the urban scene changed, with gas-lit and then electrically lit shop windows offering Christmas gifts. Hand-made toys were joined by mass-produced goods: little trains with rails, and expensive dolls.

People of the cities spent the Christmas season not entirely at home: a wide range of activities throughout the city tempted them out, and about. Children were taken to the circus to see clowns, animals and fireworks, magicians from abroad dazzled audiences with their magic tricks, and for adults, there were concerts and exhibitions. From 1870 onwards, people could skate every winter on the ice of the lake that later became the City Park Ice Rink. At Christmas time, ladies and gentlemen glided on the ice to the sound of a military band.

The poet Petőfi makes a star

Civic families celebrated not only in the family, but friends and relatives would often go over to each other's houses and decorate pine trees together, play cards after dinner, or make indoor fireworks by the fireplace, for which the tools could be bought in shops. Well-off families also organized dances and get-togethers for their friends. Dóra Kovács also quotes from the memoirs of Mária Csapó, who, in the early 1840s, was 13 years old when she and her mother went to a dance after the distribution of Christmas presents at home. It was here that she first danced with her future husband, Sándor Vachott. A few years later, she was celebrating Christmas as Mrs. Sándor Vachott in her own beautiful apartment with her husband and his writer friends. Among those invited was the young poet, Sándor Petőfi, who arrived when they were decorating the pine tree and helped his friend to hang colourful stars on it. Later, as is the old custom, they gathered around the tree and made a star for Mária’s sister Etelke.

It was a twenty-four-point star, with a man’s name on each vertex. Petőfi, who loved Etelke, wrote a short poem for her on one of the vertices.

Etelke had to put this star under her bed and cut off a vertex in the darkness at dawn. According to superstition, the name on the cut vertex told the girls who their future husband would be.

Resources:

- Bálint Sándor: Karácsony, húsvét, pünkösd; A nagyünnepek hazai és közép-európai hagyományvilágából, http://mek.niif.hu/04600/04645/html/index.htm

- Podhorányi Zsolt: Gyerekek a kastélyban, Kossuth Kiadó, 2019.

- Káli-Rozmis Barbara: Erzsébet királyné a születésnapját Gödöllőn ünnepelte/tumag.hu

- Rónay Jácint: Erzsébet királyné udvarában (1871-1883), sajtó alá rendezte Vér Eszter Virág és Borovi Dániel, Erdélyi Szalon Kiadó, 2022.

- Kovács Dóra: „A királyék megint itthon vannak!”, Álomgyár Kiadó, 2020.