How was complementary feeding done a hundred years ago?

"Oh, Tommy ate stuffed cabbage at Tibi's wedding when he was four months old, and it didn’t hurt him" - we've all heard similar wisdom when it comes to complementary feeding. It is often difficult for young mothers to confront these typical socialist-era beliefs. But the knowledge we have today was already there a hundred years ago, only it was later superseded by the barbaric, inhuman worldview of the communist state party in this area too.

My favourite of the poet, Dezső Kosztolányi's letters are the pieces written in 1915, in which he tells his wife about his son Ádám. His wife, Ilona Harmos was being treated for pneumonia in the Tátra mountains at the time, so she was forced to take some time away from her five-month-old son. I wonder how they managed to feed him? What did children eat at that time? We can read about it in our old cookbooks.

Where did the milk come from?

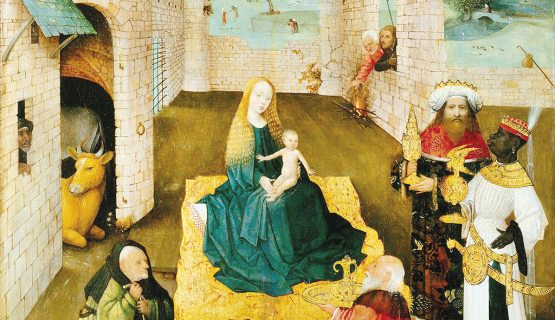

"Even mothers are healthier if they breastfeed, which makes the milk more abundant", wrote Peter Pázmány in the 1600s. The promotion and appreciation of breastfeeding were typical of the Catholic Church (we might recall paintings of Mary breast-feeding the baby Jesus), while wet nurses became fashionable in the Enlightenment period. Of course, if a mother was unable to breastfeed her baby for some reason, relatives or wetnurses came to her aid. And when the district nurses’ service was organized, the collection and distribution of breast milk began. The Kosztolányi family did not take advantage of this opportunity, and five-month-old Ádám was initially given pasteurized milk from the Károlyi estate in Fót, which "worked very well". Although the cookbook of Erzsébet Hunyadi from Bánffyhunyad was published ten years later, in 1925, it still reflects the feeding habits of the time. The author wrote the principles in consultation with doctors and teachers in Budapest. As she writes, improper nutrition can cause illness and digestive disorders later on, so it is important to set aside time to get informed.

She recommends exclusive breastfeeding up to six months of age (refuting later misconceptions, she makes it clear that neither water nor tea is needed as a supplement), but not on demand, but every 3-3.5 hours.

Ilona Harmos was also breastfeeding, and they were worried that the illness might have affected the milk the baby was receiving. It was only after her admission to a sanatorium that cow's milk came. We know from Hunyady's cookbook, cow's milk was diluted with water or tea and enriched with flour (the so called ‘children's flours’, such as Kufeke, Szitmaltin, Maltosit or Demaltos contained milk powder, malt extract, egg yolk and were flavoured with sugar or cocoa). The Kosztolányi family gave the baby tea in addition to milk, first with saccharin (also mentioned in the cookbook), then switched to sugar on doctor's orders.

The first spoonfull of food

At first, the baby's menu was supplemented with oatmeal soup, and then on 9 October 1915, "he was given his first apple preserve, carefully boiled and warmed twice", his father wrote in a letter (the apple's phosphorus content is a bone-strengthener). On October 15, "Baby gets toast-bread (he loves them) soaked in hot milk, and carrots, etc. Baby is very greedy. He just shakes for his food. But he digests everything very well, even the toasts!" Ilona Harmos must have thought this was premature because Kosztolányi wrote several times to reassure her that the baby had no problems with the toast. But the mother must have been right, because later on the baby had to have an enema and visits to the doctor, and after that little Adam could only have half of a toast.

In the Hunyady cookbook, milk-soaked buns, sponge cakes, or toast are only mentioned from the age of one.

The Kosztolányi's son, however, was already eating bread at the age of six months, and from the end of the month onwards the father, who always wrote with loving care about his son, could report increasing success. "He is getting fatter. The other day we gave him a little raspberry juice. How he loves it! He's a gourmet. His father's son. [...] Baby is having lunch now: mashed potatoes and applepurée. He likes applepurée, but he doesn't like potatoes at all. He blows it back into the spoon!" – a note from November 1915. This is in line with Hunyady's instructions. She also says that the first thing to try is the broth. Then you could add grits and tapioca to it, and then purées - first of all of the soup vegetables, spinach and potatoes. Then came orange juice, apple and plum purée, and mashed bananas. From the age of ten months onwards, it was milk-based semolina pudding. The meat was not recommended until the second year in Hunyady's book, and whole eggs until the third year - yolks were allowed earlier.

Soups, stews, light soufflés, sponge cakes and some meats (chicken, veal, venison, rabbit, for example) are recommended for three-year-olds, while the earliest age at which a child can fully adopt the family diet is four years, according to the 1925 recommendation.

Roux is only used from the second year onwards, and before that, you can read about puréed stews made with butter and milk in the cookbook, for example, peas, cauliflower, lentils, beans, carrots, spinach. So there is no sign of stuffed cabbage or pig’s feet and tripe. After the Second World War, sugar-sweetened water, baby formula, and semolina pudding were only given as a last resort. But exclusive breast milk, fresh vegetables, and selected, high-quality meats were already important foods for babies in the 1920s.